Why an iconoclastic Jewish scholar thought Islam held a key to improving Judaism

Pioneering author Ignaz Goldziher was a lifelong champion of Talmud but rejected hidebound observance

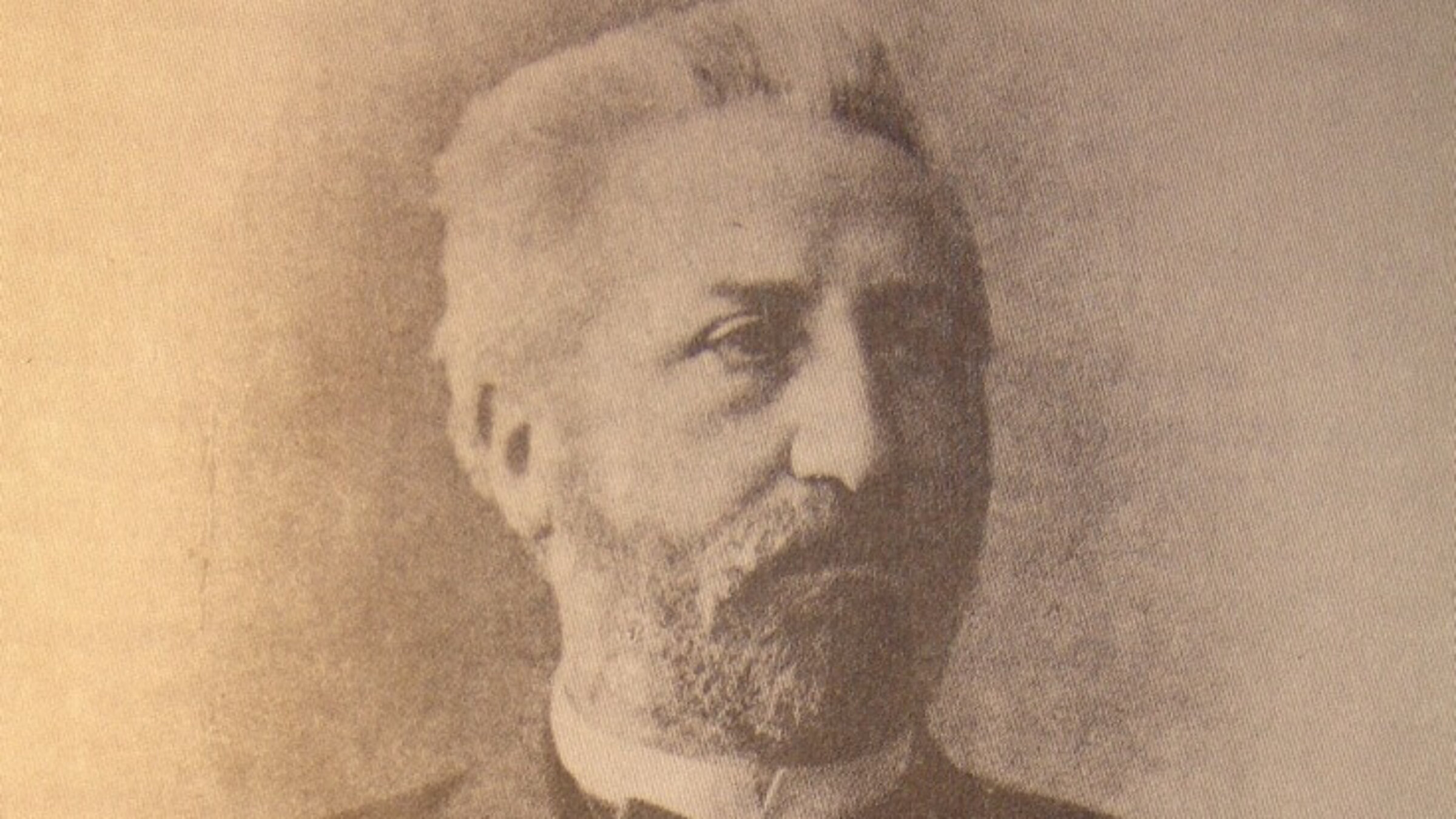

Born in Székesfehérvár, central Hungary, Ignaz Goldziher began to study Talmud at age five. His first book, on the origin, of prayer, was published when he was 12. Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Ignaz Goldziher died just over a century ago, but his achievements as a Hungarian Jewish pioneer in modern Arabic and Islamic studies are still cherished. Such dauntingly masterful studies as On the History of Grammar among the Arabs and Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law are still revered by mavens. A new book, Ignaz Goldziher as a Jewish Orientalist, by Tamás Turán, explores how Goldziher fit into a generation of Jewish specialists in all things Islamic.

Susannah Heschel has noted that 19th century Jewish thinkers found affinities with Islam, especially for better opposing Christianity. To these researchers, Islam and Judaism were rationally obsessed with law, rather than merely testing belief, which in Christianity led to such atrocities as the Inquisition.

To these reactions, Goldziher added a vehement preference for Sephardic Judaism, harkening back to centuries ago, when leading Jewish intellectuals wrote in Arabic for readers in Muslim Spain. For Goldziher, Sephardic culture was no mere nostalgic excursion. He felt that Judaism might benefit from refinement according to the best elements of Islam.

Favoring progressive aspects of both religions, Goldziher rejected what he saw as hidebound traditional Jewish observance, with rabbis “snorting away” at Bible stories or “soul-killing” prayer books.

After an Orthodox upbringing, he became relatively lax about matters such as kashrut, especially when traveling, but continued to study a daily page of Talmud to hone his intellect for the challenges of Islamic research.

In 1914, Goldziher wrote to the linguist Abraham Shalom Yahuda, born in Jerusalem to an Iraqi Jewish family:

“Whatever Jews possess in terms of religious culture is of Sephardic origin. Everything is connected to [Yehuda] Halevi and Maimonides. [Moses] Mendelssohn is unthinkable without this connection. Remain a Sephardi and a champion of a Sephardic Renaissance.”

Goldziher himself remained a lifelong champion of the Bible and Talmud. His Mythology Among the Hebrews refuted contemporary accusations that Jews had purloined myths from other cultures, a notion advanced by the Frenchman Ernest Renan, who decried a supposed lack of Semitic epics, science or philosophy.

Born in Székesfehérvár, central Hungary, Goldziher began to study Talmud at age five. His first book, on the origin, of prayer, was published when he was 12. His mentor, the Talmudist Moses Wolf Freudenberg, accorded him a Latin nickname: Ignatius autorculus (Ignaz the author).

At his bar mitzvah, Goldziher preached a sermon lasting one hour, followed by Talmudic discourse later in the day; by that evening, he had brought himself to tears with his own eloquence.

By age 16, he was enrolled at Budapest University, having mastered Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish and Persian. Still in his teens, he wrote a doctoral dissertation on Tanhum ben Joseph of Jerusalem, a 13th century Hebrew lexicographer so erudite that he was known as the “Abraham ibn Ezra of the Levant.”

Yet a promising career would be stymied by lack of a university appointment, in part because unlike some contemporaries, Goldziher refused to convert to Christianity at a time when abandoning Judaism facilitated career progress across Europe.

His wide-ranging interest in culture and tradition, not limited to narrow linguistic questions, might also have counted against him in some parts of academia. A paragon of high seriousness, Goldziher’s respect for Islamic custom was always punctilious.

In a memorial tribute, the Semitic scholar Richard Gottheil recalled how in Geneva at an Orientalist conference, Goldziher used fluent Arabic to scold some Egyptians who were “hilariously drinking wine,” suggesting that “if only out of respect for the religion they represented, they ought at least to show outward respect for its tenets.”

Tamás Turán addresses suggestions that such moralizing to others may have impeded Goldziher’s professional progress. Goldziher’s diary, written in German and published only in 1978, shocked readers with the amount of paprika it threw into the Sólet, a traditional Hungarian Jewish stew, metaphorically speaking.

Largely a plea for rachmonis (pity), Goldziher’s narrative targeted several of his colleagues, including some with staunch reputations.

One such was Ármin Vámbéry (born Hermann Wamberger), a Hungarian specialist in the languages, history and cultures of Turkic peoples. Vámbéry converted to Christianity to advance his academic career, unlike Goldziher.

Termed by Goldziher a “limping liar” and “vicious ignoramus,” Vámbéry was, Turán asserts, indeed a more problematic figure than is commonly understood. In 1900, Vámbéry informed Goldziher that his teaching job at the University of Budapest was just an excuse for lucrative quasi-espionage on behalf of the governments of the UK and Turkey: “Any man who does not acquire any money — much money — is a despicable character.” After bragging about the sums he earned, Vámbéry added that these were not obtained by dint of scholarship: “Research is a pile of Dreck.”

Goldziher could not have disagreed more with this attitude, and refused offers for foreign academic chairs, opting instead to wait it out for decades in Hungary. At age 55, he was finally accorded a salaried post worthy of his publications. Until then, he worked as secretary of the Neolog Jewish Congregation of Pest, a liberal, modernist Hungarian Jewish communal organization, in addition to lecturing at the Jewish Theological Seminary of Budapest.

In these roles he often encountered Ashkenazi Jews of whom he disapproved in his journal, using such terms as “Moravian” and “Polack” as insults. The Swiss Jewish scholar Edward Ullendorff compared Goldziher’s critique of fellow Jews to “The Self-Tormentor,” the protagonist of a stage comedy by the Roman playwright Terence.

Decidedly unmerry, Goldziher was typically an intense diarist; during one voyage, he ran out of ink but continued scribbling away, dipping his pen into shoe polish to capture his thoughts. He bemoaned his status as the “despised and ill-used lackey of my purse-proud and ignorant coreligionists.”

His fellow Hungarian Jew, the ethnographer Raphael Patai, implied that Goldziher was a manic depressive in need of psychological counseling. More empathetically, the German Jewish historian Shelomo Dov Goitein called Goldziher’s journal a “human document of tragic dimensions.”

By contrast, Turán explains Goldziher’s mood swings by citing the German Jewish philologist Heymann Steinthal’s characterization of Semites, especially Israelites, as a mix of “excitability” and “earnestness.”

Add a dollop of what Ismar Schorsch, Chancellor emeritus of The Jewish Theological Seminary, characterized as “The Myth of Sephardic Supremacy in Nineteenth-Century Germany,” and Goldziher’s vehemence may appear a bit more explicable.

Even-handed in his obloquy, Goldziher also castigated offending Muslims, not just the bibulous Egyptians confronted in Geneva. In Istanbul, he called a performing dervish, a whirling Sufi Muslim worshiper, a “miserable God swindle,” and considered that observance of Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, observed by fasting, prayer, and reflection, was likewise part of a “swindle” perpetrated against believers.

Invective aside, posterity will surely look upon Ignaz Goldziher’s publications with gratitude for their enduring probity and coherence. When Goldziher’s private library was purchased in the 1920s by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, one young intellectual, Gershom Scholem, thrilled that the “famous library of the even more famous Islamist” should be accessible to Jewish researchers. The excitement persists in the scholarly community about Goldziher’s work, regardless of his opinions of others, justified or not.