This visionary Jewish writer had several aliases, so it’s hard to know who she really was

There was a brilliance to Anna Margolin’s writing, but also many great mysteries

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

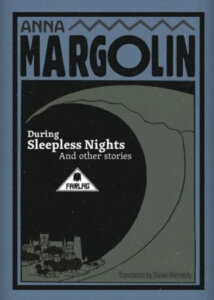

During Sleepless Nights and Other Stories

By Anna Margolin, translated by Daniel Kennedy

Farlag, 88 pages, $15

The great Hebrew poet Chaim Nachman Bialik once wrote the great Yiddish poet Anna Margolin (1887-1952) a fan letter, which read in part: “Who are you? It seems that until now I have not come across your name. Your poems are genuine. You are a true poet. I wolfed down your book as soon as it fell into my hands.”

Bialik’s question — “who are you?” — popped into my mind as I read During Sleepless Nights and Other Stories, an 88-page collection of Margolin’s fiction translated by Daniel Kennedy, because the stories in this collection were written under multiple pen names. She famously lived an unusual, rebellious life for a woman of her time — and many of her literary peers believed that her poetry was written by a man.

Margolin was born in Brisk in 1887, then part of the Russian Empire, in what is known as Brest in Belarus today. Brisk has an important place in the history of Orthodox Judaism; Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, the grandfather of Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, also known as the Rav, accepted a position as the rabbi of Brisk. But Margolin’s father made a striking choice: He decided to give his only daughter a European education.

As a child, Margolin lived briefly in Königsberg and Odessa, and then made her way to Warsaw, where her father lived after divorcing her mother. In 1906, her father sent her to New York to prepare for a university entrance exam.

Instead, she hung out with the Lower East Side’s bohemians. She eventually left New York and traveled to London, Paris and Warsaw, where she met and married the Hebrew writer Moshe Stavski; they moved to Tel Aviv. But Margolin didn’t like living in Tel Aviv, then a small town. She went back to Warsaw, leaving her husband and baby son behind.

In 1913, she moved to New York again — and this time, she stayed. Margolin then joined the new Yiddish newspaper Der Tog in 1914, where she wrote a weekly column on women’s lives as well as plenty of pro-suffragette pieces, and of course she wrote poems.

It’s tempting to look at Margolin in terms of years active. “Her career as a poet did not last long, but it coincided with the most intensive decade in the course of modern Yiddish poetry, a period that also marked the beginning of woman’s poetry in Yiddish as a separate literary corpus,” the scholar Abraham Novershtern wrote.

But what matters with Margolin is the sensual, often blunt and even jarring nature of her poetry, which captures life in 1920s New York, and the lasting effect it has had on readers and in particular other poets decades later. For the uninitiated, here is the opening stanza of “Years,” in Shirley Kumove’s translation:

Like women well-loved yet still not sated

Going through life with laughter and rage

Eyes gleaming with fire and agate —

That’s how the years were.

The second stanza mentions Hamlet, and the third has God and a shattered piano.

These kinds of juxtapositions have attracted poets and artists of all kinds to Margolin. Feminist icon Adrienne Rich translated Margolin, and the beloved Israeli singer Chava Alberstein set Margolin’s words to music. So even though Margolin stopped writing poems in 1932 and lived the rest of her life as a recluse, her voice still lives — in Yiddish, in translation, and in music.

Portrait of a young writer

All this fandom made me curious to read her fiction. Margolin used two different pen names in her stories — Khave Gross and Khane Barit — and she apparently wrote stories well before she won acclaim as a poet. And of course, “Anna Margolin” was also a pseudonym; her given name was Roza Lebensboym.

The design of During Sleepless Nights and Other Stories retains the history of Margolin the poet by including a snippet of her poetry in the opening page of the collection. It also retains a bissele Yiddish by printing each story title in Yiddish and in English translation.

The translator, Daniel Kennedy, previously translated Shamma Weitz by Isaac Bashevis Singer, as well as three books by Hersh Dovid Nomberg and one by Zalman Shneour; Kennedy is part of a new generation of active Yiddish translators who are bringing writers into English for the very first time.

Margolin’s stories fall somewhere along the line between poetry and prose. “From a Diary,” attributed to “Khane Gross” — one of Margolin’s noms de plume — is a series of diary entries. The narrator is a young woman in love with a man who clearly has other women in his life besides her. She tracks down one of his lovers and becomes obsessed, following her around:

“Later, I noticed that whenever she was alone in a place where he was likely to turn up, she’d be nervous with a downcast gaze and a pitiful smile on her pale face. I knew she was his lover and so I paid close attention to her appearance: a pallid, inconsequential face — one of those unmemorable faced you encounter wherever you go — dull, close set eyes, altogether somber and gray. I was curious to hear her voice, so once I casually asked her if it was cold outside. Her voice was shrill and childlike; it didn’t suit her aging face.”

Things escalate from there. The narrator visits the other woman’s address, and feels “pity for him” as he describes this other girl to the narrator as a “very important friend.” Yet there is constantly the theme of books as in this diary entry in its entirety:

“My books, my great friends, gaze down on me with quiet resentment, calling me to them.”

The 17th entry reads “ I have returned to my books. I’ve been working a great deal today, to the point of intoxication.” What’s intoxicating for this reader is realizing that a woman wrote these words in 1909.

“From a Diary” is also a lovely portrait of the life of a young writer — the joy of work, the love of literature, and the ambition.

“Once again, I’m delving into my work with elation,” she writes in the entry titled “Night.” “I’m young and strong and not afraid to stare my sorrow in the eyes, drinking it down to the dregs. And because I am young and strong the work draws me in, just as life does the joy of life.”

Epitaph for Anna Margolin

Three of the four stories here were written when Margolin was just 22, and some of that early-career awkwardness can be felt here. And while the writer was very young, these stories seem very concerned with aging, and sometimes, a bit obsessed with the subject.

“In France,” also written by “Khave Gross” in 1909, features a man who lives with his 17-year-old daughter, while his wife lives in a small village somewhere. Much of the dialogue is about the stress of getting and looking older.

Perhaps because Margolin’s fiction constantly refers to age, I found myself thinking about the experience of reading early work, and whether there needs to be some sort of disclaimer in the reader’s mind, something along the lines of “just getting started and figuring things out.”

I also found myself wondering if an introduction beyond the paragraph about Margolin’s life on the back cover would help readers — especially those who are not Yiddishists — enter the world of these stories.

But can anyone really know Margolin? Would an intro really help?

Bialik caught that fundamental mysteriousness immediately. As for Bialik’s question — “who are you?” — Margolin’s tombstone, at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Queens, New York, provides what is perhaps a final answer. It features her poem “Epitaph” — translated here by Kumove:

She squandered her life on rubbish, on nothing.

Perhaps she wanted it so, perhaps she desired this misery, these seven knives of anguish to spill this holy living wine on rubbish, on nothing.

Now she lies with shattered face. Her ravaged spirit has abandoned its cage. Passerby, have pity, be silent — Say nothing.