It was the million-selling novel that shaped a generation of Jews — does anybody still read it?

Leon Uris’ epic ‘Exodus,’ and the film it inspired, once played a crucial role in changing American attitudes to Israel

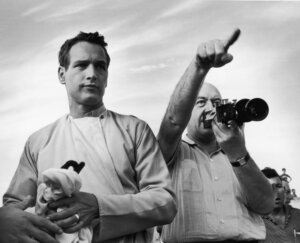

Actor Paul Newman visits Masada, in Israel, in 1959, while he was there filming the movie “Exodus”. (Photo by Leo Fuchs/Getty Images)

Terry Kraus was a 12-year-old transfer to a new school in Arizona in the 1960s when a classmate picked on her for being Jewish. A sympathetic teacher saw the exchange, and slipped her a book: Exodus, by Leon Uris. After school, Terry went to her friend’s house for a playdate. But she ended up so engrossed by Exodus that she spent the afternoon reading the book, instead of playing with her friend.

George Cox was a Christian teenager in Oklahoma, the son of an American soldier who helped liberate Dachau but never spoke of his time in the war. Reading Exodus in 1958, the year it was published, Cox was enamored by the book’s depiction of a struggle between good and evil. He saw the founding of Israel as a continuation of the themes of World War II — the next stage of the fight for good.

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify:

Sue Reinhold, now 58, was in her 40s when she read Exodus in 2007, around the time when she converted to Judaism. Her girlfriend at the time, a Jew and the child of Holocaust survivors, told her that in order to fully become a Jew, “You gotta read Exodus, and you gotta watch Fiddler on the Roof.”

“Reading Exodus, it was kind of like: whoah,” Reinhold said. History books, Wikipedia pages, Golda Meir’s memoir — none of them came close, she said, to presenting Israel with a narrative as vivid as that of Exodus.

I was studying for my bat mitzvah in 2006 when my dad, a Reform rabbi, pressed a battered paperback into my hands. The cover of my copy of Exodus showed what looked like a Swedish Barbie in combat gear, standing next to a Clark Gable-look alike holding an M16.

I experienced the phenomenon for which the book is famous: a longing to live in the righteous, bloody, world Uris created. And with that feeling, the strength of my attachment to that fictional Israel transmuted into an attachment to the real Israel. Except the thing I loved did not quite exist — a fact that united me, I think, with many Jews who care for Israel.

Published in 1958, 10 years after what Israelis call the founding of their country and Palestinians call The Nakba, or the catastrophe, Exodus is one of the stranger artifacts of 20th century literature: a 626-page novel that, in fictionalizing many of the historic events surrounding the formation of the state of Israel — Holocaust narratives, independence battles, sensual encounters in Tiberias — ended up shaping not just generations of American perceptions of Israel, but policy, too.

‘God gave this land to me’

After its publication, Exodus immediately rose to the top of The New York Times bestseller list, where it stayed for a year. The publisher claimed that the advance paperback order was the largest in history. In 1960 the novel was adapted into a movie starring Paul Newman, which was a box-office smash. Even the movie’s theme song, “This Land is Mine,” charted in the Top 40. Its lyrics: “This land is mine! God gave this land to me.”

Never mind that since the novel’s publication, historians have said that Exodus is more fairytale than documentary: Uris’ seductive narrative clearly fostered fidelity to the Jewish state. Running for president in 2008, both Barack Obama and John McCain wooed Jewish voters with mentions of reading Uris. In 2015, then-Vice President Joe Biden introduced Obama at a celebration for Israel’s independence day, saying, “As a young man, he grew up learning about Israel from the stories of Leon Uris in Exodus.”

Few are immune, especially those given to a romantic view of history — a 2010 profile of Tom Hanks noted that Uris’ novels, including Exodus, “taught Hanks to feel history in a way no high school teacher ever did.”

But for all that Exodus is still one of the most common cultural texts people reference when discussing Israel, it hasn’t had the staying power of, say, Fiddler on the Roof. (Consider Exodus’ sub-100,000 ratings on Goodreads, in comparison to the over 400,000 ratings garnered by A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, another midcentury epic.) It’s more like Gone With the Wind: a novel that changed a generation, then fell out of favor, but is still deeply embedded in the conscience of an older generation.

That generational rift reflects a more general one among American Jews. Per the Pew Research Center’s 2021 survey of American Jewry, only 48% of respondents ages 18-29 said they were emotionally attached to Israel, compared to 67% of respondents ages 65 and older.

I set out to learn how Exodus had impacted individual American readers — and how their impressions might have changed over time — because I wondered if American Jews might understand each other better if we talked not about Israel, but about Exodus— if we turn away from the din of the discourse and attempted to understand what very different narratives different generations have received.

The people I spoke to are not a representative sample of American Jews. They are friends, or friends of friends, which means that their Judaism leans Reform, and their politics lean progressive. I wanted to talk to members of my own community to try to understand why it feels like we cannot talk to our own parents, children and neighbors about Israel.

‘Everybody I knew was totally in support of Israel’

Exodus begins by invoking the words of God as spoken to Moses, exhorting him to lead the Jewish people to Israel. But its action starts in 1947 Cyprus, where child survivors of the Holocaust are held behind barbed wire, prevented from entering Mandatory Palestine by the British.

There, our hero, underground Israeli military leader Ari Ben Canaan, meets his heroine, Kitty Freeman, a nurse so WASPish and lovely she sounds like she belongs at a Norman Rockwell soda counter.

Together, they breach Mandatory Palestine on a ship, called The Exodus, filled with child survivors. They develop new agricultural methods and turn the desert green; rout the British; declare Israel a Jewish state; and fight the Arabs. They fall in love, but never as deeply with each other as they do with the land.

The genius of Exodus was Uris’ realization that the best way to market a new nation is not through a speech or an editorial or a radio announcement or an anthem or a newly printed map, but rather through a story.

In a way, he made a bible.

Alan Rothenberg, 78, was the child of Jewish immigrants who escaped Vienna before the war and landed in West Virginia. “My parents weren’t great Zionists — they were serious Jews, but they felt that this whole process of what happened in Israel was sort of a luxury they couldn’t devote a lot of time to,” he says. But when his family saw the film adaptation of Exodus in 1960, it gave him a different sense of connection to the young state. “I was a Jew, they were Jews. They were helping people escape, my parents escaped.”

Watching Exodus as a teenager, Susan Rothenberg, 77,watched her father “glow and get teary.” He had left Europe before the war, and his family members had been killed in concentration camps. Through Exodus, Susan, who is married to Alan, could better understand why her father was “ecstatic” over Israel’s founding. “How nice that there is a place now, where Jews can be safe,” she remembers thinking.

There “was a period of time, unlike today, when everybody I knew was totally in support of Israel,” Jill Zerin, 88, told me. “There was not a question about the value, the importance of Israel.”

“I was bubbling with enthusiasm reading the book,” said her husband, Rabbi Ed Zerin, 102. (Ed Zerin, z”l, passed away shortly after this interview.) In 1948, Zerin was a rabbi at a congregation in Des Moines, Iowa. He listened anxiously to the radio as the United Nations voted for the 1947 partition of Palestine. In the years that followed, though, he had to be very “careful” in speaking about the nascent Jewish state with his congregation.

“They were Americans,” he said. “They didn’t want their loyalty divided.” He felt hopeful, though, that Exodus might provide an inroad for explaining Israel in a way nothing else ever had.

It would be challenging to find an American Jew in the Rothenbergs’ and Zerins’ age group who escaped reading or watching Exodus. The novel was reprinted 87 times. Bradley Burston, writing in Haaretz in 2012, explains that in the wake of the book’s publication, “It was said that it was nearly as common to find a copy of Exodus in American-Jewish households as to find the Bible — and, of the two, not a few Jewish households apparently had only Exodus.”

But there has always been a gulf between the way historians and critics read Exodus — as a piece of nonsense — and the way readers received it — as transcendent. As a 1958 New York Times review put it, “This approach to the story of modern Israel strains credibility.” Commentary magazine called the book “the ultimate crystallization of the Western fantasy about Israel,” noting that Uris paints Israel as “a state whose only problem is the savage, sadistic enemies on its borders.”

In 1961, Philip Roth called the novel “bald, stupid; and uninformed” and “neither history nor literature.” The American Council for Judaism noted in 1959 that “Literary critics call it poorly written; knowledgeable Zionists label it inaccurate Zionism; historians consider it distorted history.” The novel “had nothing to do with reality,” said Ike Aronowicz, who actually captained Exodus, the ship. “Exodus, shmexodus.”

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, famously quipped of Exodus, “As a literary work it isn’t much. But as a piece of propaganda, it’s the best thing ever written about Israel.”

In her experience, Zerin said, older Jews still feel a great sense of “loyalty” to Israel. “But it’s not as unequivocal as it was.” For younger people, she says, Exodus might “actually seem kind of irrelevant.”

‘Super hot and hunky’

Part of Exodus’ appeal: It encapsulates the ways in which the project of American Jewish Zionism has relied on sex as an educational tool. In a letter to his father, Uris described Ari Ben Canaan as “a fighting Jew who won’t take shit from nobody” — a sort of sexual golem designed to save the Jewish people, with defined pectoral muscles, twinkling blue eyes, and a tenderness that thrillingly coexisted with his tendency toward violence.

Israeli poet Yitzhak Laor once wrote that the only thing he remembered of reading Exodus was a scene between Ari Ben Canaan and Kitty in which “he lowered the shoulder strap of her nightgown and cupped her breast.” Sue Reinhold remembered her girlfriend, in recommending Exodus, raving about how hot Ben Canaan seemed. “Even as a middle-aged lesbian I would think that Ari is super hot and hunky,” she said.

“I identified, body and soul, with the hero of Exodus, Ari Ben Canaan,” wrote Atlantic editor in chief Jeffrey Goldberg, of reading Exodus as a teen.

I remember being thrilled by Exodus‘ operatic romance as a teen: I anxiously wondered whether I should grow up to marry a man named Ari, or have a baby named Ari, or both. But returning to the novel in my 20s, I was struck by how the book used that allure to sell a vision of Israeli Jews who were attractive and good, in contrast to the books’ Arab characters, whom, journalist Alan Elsner wrote in 2013, rarely show up “without the adjective ‘dirty’ or ‘stinking’ appended.”

That contrast takes place, often, specifically within the realm of sex. The novel ends with a lovely, young Jewish girl being raped and murdered by a gang of Arabs. In a recent Reddit thread, a poster confessed discomfort with a rabbi’s recommendation that they read Exodus as part of their conversion process — an interesting parallel to the many people, like Reinhold, who have found Exodus to be such a significant part of their conversions.

“There’s an Arab boy who lives on the street who is willing to sell time with his sister for sex,” the Redditor wrote, pointing out that Exodus‘ portrait of Arabs is derogatory to the point of being absurd.

The moral superiority that helped make Exodus appealing in the 20th century is exactly what makes it suspect in this one. Younger American Jews often speak of a loss of innocence around Israel. At some point, they learn that the place they have often been taught to think of as the holiest in the world is best known by their peers as a site of human rights violations. This makes it hard for them to treat the story told in Exodus as credible. And it can make it harder for them to connect to older generations who, even as critical, educated, politically engaged readers, found the vision of Exodus not just powerful, but life-changing.

Shereen Sarick read Exodus in 1997. She was a young Jewish educator working at a synagogue in Aspen, Colorado, tasked with preparing children for their b’nai mitzvahs, including Rachael and Conor Uris. In thanks, their father, Leon, gifted her a beautiful, leatherbound copy of his book. (I asked Shereen if she thought this was presumptuous, and she said, “Some parents give you bupkis for tutoring their kid!”)

Even though Sarick had been teaching kids about Israel for a long time, the book made the story “come alive” for her. “A year later I went to Israel for my winter break, and that was the beginning of my love affair with Israel,” she said. She’s been back, she estimates, somewhere between 20 and 30 times.

But she’s found her love for the country almost impossible to pass along. When her own son was in eighth grade, she took him out of school for a year to travel, starting with a few months volunteering in Israel. Now, she said, “we can’t talk about Israel,” she says — their feelings about it are too far apart.

‘Maybe I’ve been deluding myself’

In some influential quarters, Exodus retains something like its original appeal: Last year, far-right Jewish political pundit Ben Shapiro selected Exodus as his monthly book club pick. And it is true that, even to my now-skeptical eyes, nothing has ever come close to presenting a picture of Israel as compelling as Exodus — not Stand With Us lectures, or IfNotNow protests, not carefully crafted historical accounts, not a dozen trips to the country itself.

In 2011, I began teaching Israeli history at a Reform Hebrew school in Brooklyn. I was determined to tell a nuanced story; to marshal the facts; to not repeat the sins of my own Israel education, which avoided mentioning Palestinians whenever possible.

But my brain kept spinning, compass-like, toward Exodus.

I found myself recounting stories about the early aliyahs and being unsure if they were historical records, or just scenes from Exodus. Listening to rabbis and other Jewish leaders preach about Israel, I noticed claims that often sounded suspiciously like talking points from Exodus: “The Jewish settlers purchased all of the land fair and square — the Arabs didn’t even want it,” or, “the land was mostly empty, anyway.” Reading celebrated histories of Israel, I wondered which politicians, writers and thinkers, like me, owed something of their perspective on Israel to Exodus.

These days, it is hard for my dad and me to talk about Exodus. While we both support Israel’s existence, and we are both horrified by the occupation, I view Exodus as a piece of vintage propaganda, a document that helped teach America to see Palestinians as subhuman. He sees it as a classic of Jewish literature. Clearly, the claims of the novel still take up space on so many of our mental bookshelves. And they hold a clue as to why conversations about Israel tend to turn so toxic, even between people who deeply love each other, like Shereen Sarick and her son, and me and my dad.

George Cox, now 80, eventually converted to Judaism. He still feels, he said, “very supportive of Israel as a state.” But looking back at his reading of the book, he’s troubled. “I think most of the people in my time back kind of thought of the Arabs sort of the way my grandparents and great grandparents had thought of the native Americans: They’re there, but we can figure it out and get around that.”

Terry Kraus, now 71, thinks Israel is a “wonderful country in a terrible neighborhood.” But her daughter, 37 and disgusted by Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, doesn’t want to hear it. It troubles Kraus. “There are six sides to a story,” she said. “Maybe I’ve been deluding myself into the wrong one for so long.”

Reinhold says her kids are more likely to be at a Students for Justice in Palestine protest than at any other kind of Israel event.

Stories are the basis of civilization. Jews are particularly besotted with them: Many of our holidays explicitly celebrate the power of stories told again and again.

But Jewish culture also emphasizes the importance of not just repeating stories, but also challenging them, and asking why we want to tell them. A novel like Uris’, with good guys and bad guys and little mention of all the displaced people, was never going to be a long-term fit for a culture so obsessed with taking a magnifying glass to complicated narratives. Now, the American Jewish relationship to Israel and Palestine demands more stories.