In the history of the artichoke, a history of Sephardic Jews

The glorious vegetable made its way from the Iberian Peninsula during the Inquisition to Sicily and then to the Jewish Ghetto of Rome

With its multiple layers of sage-green and sometimes purple-tinged triangular leaves forming a stately bud-like cone, the artichoke rewards the patient connoisseur. Photo by Liza Schoenfein

There are plenty of ingredients that warrant the distinction of Iconic Jewish Ingredient — foods that show up throughout the Jewish Diaspora, often appearing across Ashkenazi, Sephardi and Mizrahi cuisines. These ingredients — sesame seeds, raisins, cabbages and eggs among them — help define the flavor and character of a wide array of Jewish dishes.

But what about an ingredient that’s utterly essential to a specific Jewish community but has limited proliferation beyond the region? If, when you think of that locality, the first dish that pops to mind is a beloved specialty embraced throughout the area (and outside of it only to some extent), is its main ingredient worthy of “icon” status?

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify:

The locality I’m considering is Rome — in particular its Jewish Ghetto — and the dish is carciofi alla Giudia, Jewish-style fried artichokes.

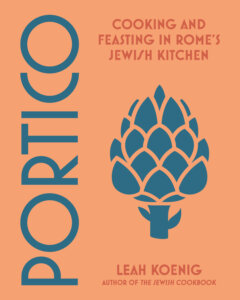

“There is perhaps no greater love affair on earth than the flame that burns between Roman Jews and artichokes,” Leah Koenig writes in her upcoming cookbook, Portico: Cooking and Feasting in Rome’s Jewish Kitchen. “The ancient Mediterranean thistle … serves as a totem of the community’s identity.”

Well, if that’s not a resounding vote for inclusion in the pantheon, I don’t know what is.

Artichokes are members of the aster (Asteraceae) family (also known as Compositae), which also includes cardoons, various chicories and tarragon, along with sunflowers, chrysanthemums and chamomile. Originally grown along the Mediterranean and in North Africa, the plant is known to have been eaten by the ancient Romans. For centuries thereafter, though, the artichoke seemed to lose favor, until the Moors began growing and eating them in Spain and the Spanish-ruled island of Sicily during the Middle Ages.

The history of carciofi alla Giudia follows the path of Sephardic Jews who, when expelled from the Iberian peninsula during the Inquisition, made their way to Sicily, where they were introduced to the delicious-if-prickly edible thistle. Exiled once again in 1493 after the Inquisition reached the island, Jews made their way north, bringing artichokes with them. And it was when they got to Rome that the artichoke magic happened.

One wonders who first picked an artichoke and — while carefully avoiding the tiny thorns at the tips of all those tough, tightly packed leaves — thought, “This looks like something good to eat.”

Not that the artichoke isn’t a magnificent vegetable to behold, with its multiple layers of sage-green and sometimes purple-tinged triangular leaves forming a stately bud-like cone. It’s just that it takes patience and determination — and in the case of the OG artichoke eater, imagination — to decide to whittle the thing down to a state of edible glory.

“It took a leap of culinary inspiration — or desperation — to say ‘let’s eat that,’” Koenig told me recently, when I turned to her for information about artichokes in Roman Jewish cuisine. (They’re such a focus of the new book that she chose an artichoke graphic for the cover.) She added that non-Jews in the south of Italy shunned the artichoke, calling it “the Jewish vegetable.” Lacking the financial resources to be choosy, Jews learned a thing or two from the tasty preparations coming out of Moorish kitchens.

So what happened in Rome to turn the artichoke into the undisputed star of Roman Jewish cuisine? The answer is simply this: hot oil.

Romans were experts at frying all manner of foods, and while there are certainly many wonderful ways to prepare artichokes, nothing results in a more pleasurable eating experience than deep-frying them whole. Thus carciofi alla Giudia was born, becoming one of the most popular dishes not only within the Roman Jewish Ghetto but beyond it, in and around Rome.

Luckily, you don’t have to venture to Italy in order to find them. Check the menus of your local Italian restaurants, especially in spring when artichokes are in season. I’ve enjoyed them at New York’s Trattoria Dell’Arte many times, and recently noticed them on the menu at Noi Due Carne, a kosher Italian Mediterranean spot on the Upper West Side.

Speaking of kosher, artichokes are not without controversy. During Passover 2018, Israel’s chief rabbinate declared that artichokes prepared whole — as they are in the Roman-Jewish specialty — could not be considered kosher since small bugs might hide within their leaves. Never mind that religious Roman Jews had been preparing and consuming them for over 500 years.

With its most popular dish threatened (along with the livelihood of Jewish restaurateurs throughout the area and the personal integrity of Roman-Jewish home cooks, who pride themselves on their ability to properly clean their carciofi), seemingly all of Rome went up in arms. Rome’s chief rabbi, Riccardo Di Segni, not only rejected the decree but shot a video of himself cooking carciofi alla Giudia while offering holiday wishes to his constituents.

And while making them is no small task, you too can do it at home. In Portico, Koenig offers the traditional method, which involves trimming the artichokes and then double-frying them to achieve the perfect crisp-on-the-outside-tender-on-the-inside consistency. There’s also a simplified recipe that calls for canned or jarred artichokes, which saves all the trimming time.

I can certainly see the benefits of that, but I’ve grown to enjoy the prep, which is not so much difficult as it is a process. There’s a very good photographic how-to in Koenig’s book, and I went ahead and shot a step-by-step video of myself trimming artichokes, which should demystify the whole experience for anyone who’s carciofi curious.

How to Prep Artichokes

Once you know how to do it, there are any number of artichoke dishes to make, most of them quite simple. “Portico” includes a recipe for artichokes alla Romana, another classic, in which the vegetable is braised in water and wine rather than fried; and one for a salad in which raw artichoke hearts are sliced thinly and served with shaved Parmesan.

Deep into artichoke season and well into my research, I was drowning in trimmed artichokes and looking for easy ways to use them. I discovered a method that’s more hands-off than frying and requires a lot less cleanup: Cut the trimmed vegetables in half or quarters, drizzle them with olive oil, salt and pepper (making sure to get between the leaves) and roast them in a 400-degree oven for about 10 minutes per side. To eat them, dip the burnished crispy leaves in aioli, Sriracha mayonnaise, or mayo mixed with a little Dijon, garlic and lemon juice before relishing the tender heart, which is perhaps more delicious for the labor it took to reach it.