The secret Jewish history of ‘American Graffiti’

The classic 1973 film presents a whitewashed vision of America; its soundtrack was anything but

Mels Diner, founded by two Jewish businessmen, Mel Weiss and Harold Dobbs, plays a key role in George Lucas’ film. Photo by Getty Images

The first image viewers see when watching American Graffiti, the quintessential movie about late-1950s/early 1960s automotive and rock ‘n’ roll culture that is celebrating its 50th anniversary on Aug. 11, 2023, is a shot of Mels Drive-In. Mels serves as a kind of home base throughout the film, with much of the action emanating from and returning to the burger joint, which boasts servers on roller skates and music blasting from loudspeakers into the parking lot.

Basing the movie at Mels was just one of the many touches of verisimilitude that lent American Graffiti its veneer of authenticity. By the time the movie takes place, in summer 1962, Mels was a real-life chain of drive-ins spread across Northern California. The original Mels opened in San Francisco in 1947, founded by two Jewish businessmen, Mel Weiss and Harold Dobbs. Dobbs, born in 1918 to Russian Jewish immigrants, was a big macher in San Francisco and its Jewish community — a lawyer, businessman and politician who served as president of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors.

The first song you hear in American Graffiti is “Rock Around the Clock,” recapitulating its essential role in the 1955 movie, Blackboard Jungle, one of the very first films to portray the emerging teenage “culture” fueled by early rock ‘n’ roll. As I wrote previously in these pages, the song was written by two Philadelphia-born Jewish songwriters named Max C. Freedman and James Myers.

The songs used in American Graffiti are as important as the human characters; they function as a kind of backbone to the scenes of aimless cruising up and down the main drag running through downtown Modesto, California, where the film takes place. The songs are used diegetically, meaning as part of the action — appearing within the story itself, mostly heard over car radios, and not as a background score meant to set a mood for the viewer.

Of the 40-odd numbers selected by director George Lucas, fully a quarter are written by Jewish songwriters. Harrison Ford’s character sings a few lines of “Some Enchanted Evening,” a show tune from the 1949 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical South Pacific. The movie also includes “Love Potion No. 9,” written in 1959 by the Jewish songwriting duo of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. The song “At the Hop,” which launches an important scene in the film, was co-written by Artie Singer, the Toronto-born son of a hazzan (cantor). Singer settled in Philadelphia and performed at High Holiday services for over a half-century in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and elsewhere.

“See You in September,” performed here in its original 1959 version by the Tempos (it was later a top-five hit by The Happenings in 1966), was co-written by Sid Wayne, born Sidney Weinberg in Brooklyn, and Sherman Edwards, who grew up in the Weequahic section of Newark, New Jersey, and who went on to write the songs for the 1969 Broadway musical 1776. The early R&B vocal group the Platters are heard thrice in the film, once singing their 1958 version of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” co-written by Jerome Kern; again with their 1955 hit, “The Great Pretender,” written by Buck Ram, born Samuel Ram in Chicago in 1907, to Jewish parents; and again with the Platters’ version of Ram’s 1955 hit, “Only You (And You Alone).”

Other Jewish-penned songs in the movie include “I Only Have Eyes for You” by the Flamingos, with lyrics by Al Dubin; “You’re 16,” a top 10 hit for Johnny Burnette in 1960 and a No. 1 hit by Ringo Starr in 1973, written by the Jewish American songwriting duo of Robert B. Sherman and Richard M. Sherman — the sons of Tin Pan Alley songwriter Al Sherman, whose father, Samuel Sherman, was a violinist in Kiev until he fled a Cossack pogrom on 1903, winding up in New York City in 1909; and “Heart and Soul,” with lyrics by Jewish songwriter Frank Loesser.

To be sure, there is nothing overtly or even covertly Jewish about American Graffiti, despite the participation of Jews in many of the movie’s key creative roles (excepting the director, George Lucas), a pair of Jewish actors in lead roles, and the aforementioned songs penned by Jewish songwriters. American Graffiti is about as white – and white-bread – a portrayal of mid-century American youth as you can see.

There are no persons of color playing important roles, and I think I spotted only one Black person in the entire film — an extra, appearing for about two seconds in the lower right-hand corner of a frame. The closest the film comes to overtly acknowledging the existence of nonwhite people in the U.S. in the mid-20th century is a secondary character who boasts about his Mexican ancestry. This in spite of the fact that so much of the music heard in the film is performed by Black artists or derived from R&B, a euphemism, really, for the Black popular music that has essentially dominated the American listening experience since the 1950s.

Jews were complicit in this portrayal of a whitewashed America. Gloria Katz was one of the main screenwriters on the film. Verna Fields, born Verna Hellman — daughter of Selma (née Schwartz) and Samuel Hellman — served as the film’s editor. Sidney Sheinberg and Lew Wasserman, head honchos at Universal Studios, provided the necessary support to take American Graffiti from the realm of modest summertime hit to international box-office smash and cultural watershed.

Harrison Ford, whose mother was born Dorothy Nidelman to Russian Jewish immigrant parents, plays an enigmatic out-of-towner arriving to challenge the reigning champ of the town’s drag strip. When asked once how his mixed ethnicity served his work, Ford humorously replied, “As a man I’ve always felt Irish; as an actor I’ve always felt Jewish.”

A young Richard Dreyfuss plays a brooding character, a recent high-school graduate who professes to be noncommittal about going off to college the next day (although we never believe he won’t go). While there is nothing overtly Jewish about Dreyfuss’ character — even his name, Curt Henderson, is not remotely Jewish — certain tribal indicators in his diction and personality could be viewed as Jewish, perhaps simply because Richard Dreyfuss is playing the role.

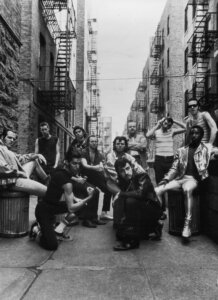

In one of the movie’s more comical side plots, Dreyfuss gets sort-of kidnapped by a “gang” of “greasers,” or juvenile delinquents, who challenge him to complete a series of pranks as a way to avoid being beaten up by them. Dreyfuss’ character meets their challenges with good humor and some astute mental planning. The greasers are so impressed with him that not only do they refrain from beating him up, they offer him membership in their group. Membership would in part entitle him to wear the gang’s sport-club-style jacket, emblazoned with their somewhat suggestive name, “The Pharaohs.”

When it was released in 1973, American Graffiti rode a wave of nostalgia for the 1950s, propelling that wave into a tsunami. The 1950s-style novelty act Sha Na Na were founded in 1969, were frequently featured on TV variety shows (including their own, which ran from 1977 to 1981), and even appeared onstage at 1969’s Woodstock Festival. Oldies radio stations like WCBS in New York City blasted ’50s and early ’60s hits around the clock, as did the nationally syndicated disc jockey Wolfman Jack, who has a cameo role in the movie. Following the success of American Graffiti, Ron Howard went on to star in the weekly TV program Happy Days, making both Howard and Henry Winkler, the show’s lovable greaser — known as The Fonz or Fonzie — household names.

Nevertheless, no one could have predicted the popularity of American Graffiti. The relatively low-budget movie earned back its expenses by a factor of about 100, and it garnered several nominations for Academy Awards, including best picture, best director, best screenplay, and best film editing. American Graffiti tapped into a simmering nostalgia for the world it portrayed, a world on the cusp of a cultural revolution. Forget about the Beatles, the ’60s, the Civil Rights Movement and the antiwar movement. The movie’s popularity and influence were an indication that a whole swath of Americans longed for an era when things appeared to be “simpler” and “more innocent.” Never mind that the seeds for the sociocultural revolution of the 1960s were being sown during the very time period the movie portrayed.

The only hint of disquietude to be found in the movie is in Dreyfuss’ character’s hesitation about leaving his hometown for college “back East.” Not yet knowing what he was rebelling against — the conformity and conservatism of the Eisenhower years, presumably — Dreyfuss’ Curt is plagued with anomie that he himself cannot recognize or explain. Throughout the hijinks he gets sucked into and the more reflective moments he shares with his friends, he sports a beatific smile, as if to say, “none of this matters.” There is little to no sense of the impending storm heading toward his world, bearing down on it with enough power to soon shake its windows and rattle its walls. In one of the movie’s final images, Dreyfuss is seen boarding a small airplane to whisk him off to college. The plane’s fuselage is emblazoned with the suggestive name “Magic Carpet Airlines.”