What do Jewish, Christian and Muslim artists talk about when they talk about ‘Genesis’?

A groundbreaking exhibit tells the story of creation through multiple perspectives, with eye-opening results

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

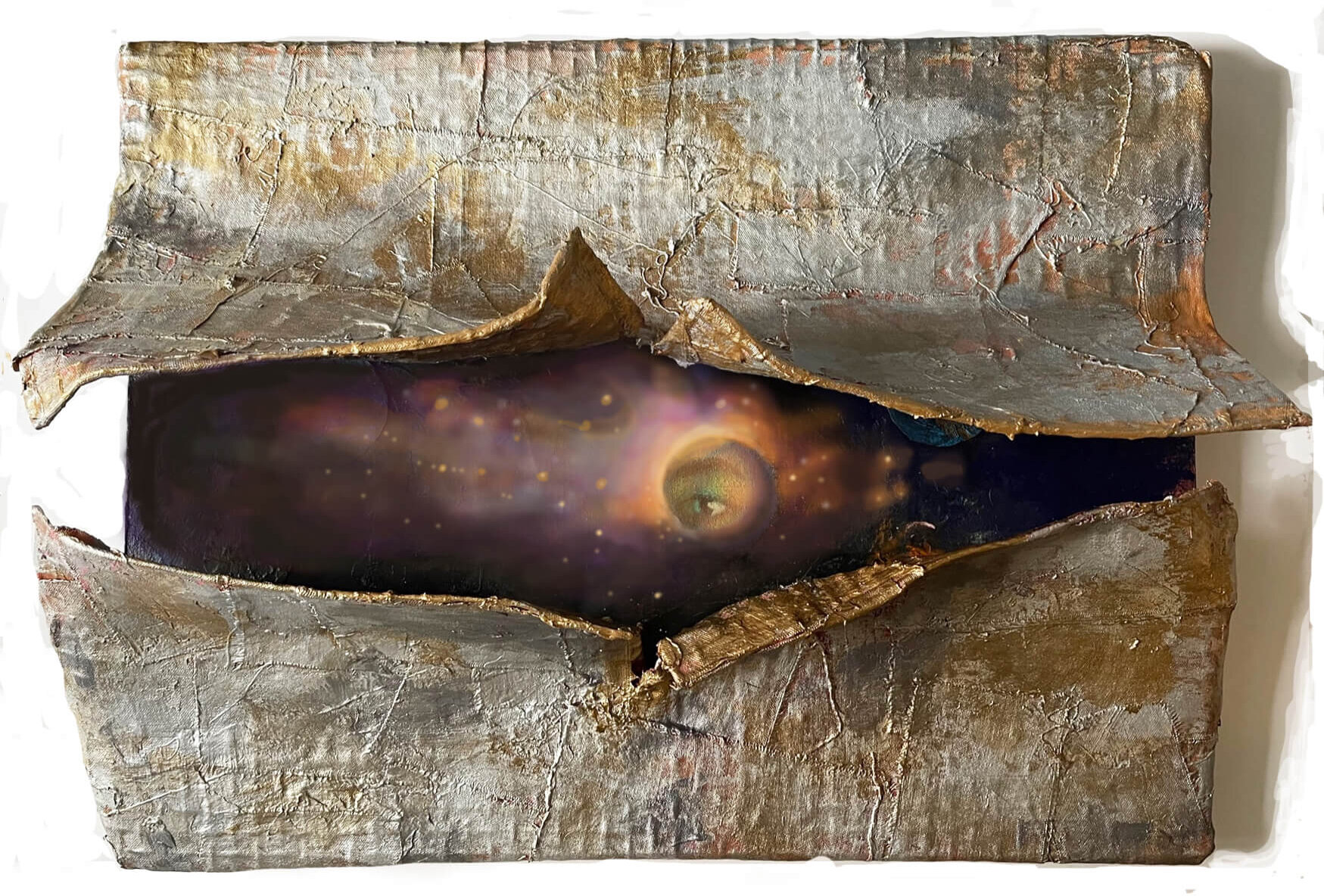

“It’s God as self-portrait,” the artist Yona Verwer told me as she explained Genesis, from Something to Nothing, an evocative but admittedly cryptic piece that she describes as “a ruptured metallic crust [which] opens like tectonic plates to provide a window to the grandeur and vast mystery of the cosmos.”

“Like God, an artist is a creator,” Verwer said. To judge by the large eye in the work’s center, an artist, like God, sees all.

From Something to Nothing is one of 14 pieces on display at the Jewish Theological Seminary in the complex, comprehensive, and unprecedented exhibition GENESIS, The Beginning of Creativity, which is taking place across three venues. Other artworks were previously exhibited at the Interchurch Center and Riverside Church. In this exhibit, it’s not anomalous for an artist to align herself with a divine force or, for that matter, view religious themes through a comic or feminist lens.

The artists explore a multitude of Genesis narratives across an array of religions. The majority of those who participated identified as Jewish, Christian and Muslim, and express a liberal perspective. Few have traditional visions of God or Genesis. One picture, by Jewish artist and exhibit co-curator Richard McBee, presents a pregnant Black Eve leading a Black Adam out of some undefined space; one assumes it’s the Garden of Eden or maybe not. They are clad in loose-fitting outfits that are timeless, surely not era-specific.

McBee, who is also an art critic, explained there’s no way not to include Black characters in the Adam and Eve story.

“This is not traditional illustrative religious art,” said Verwer, who heads the Jewish Arts Salon, a 15-year-old international network of contemporary Jewish artists and art professionals, which was the spearheading force behind the exhibition.

In addition to inviting McBee, artist Joel Silverstein, and Goldie Gross to serve as curators, the Jewish Salon also sought out the cooperation of the arts nonprofit Caravan.

The artists in the exhibit were free to tackle the theme of Genesis in any way they chose. The curators received hundreds of submissions from across the globe and selected works evenly divided among the three major monotheistic religions. They also included pieces by those who are secular, agnostic, and even atheist.

“Artists who paint religious topics are part of a growing subculture, although many of the artists might consider themselves ‘spiritual’ as opposed to religious,” said Silverstein. “The subculture also includes growing numbers of artists who are Orthodox and even Hasidic.”

“But they’re not painting dancing rabbis,” added Verwer. “Some of the new work is very interesting.”

Asked if there is a unifying aesthetic in contemporary religious art, specifically those pieces in the exhibit, Silverstein said, “Old fashioned formalism does not apply, though the works may have elements of expressionism or figurative painting or comic books. But the content is equally important, if not more so. I would call it post-formalism, meaning it’s a conversation between content and aesthetics.”

As to what degree most of the artists define themselves as Jewish or Christian or Islamic artists, versus artists who happen to be Jewish or Christian or Islamic — the answer isn’t one-size-fits-all. Silverstein, for example, said he’s an artist who sees the world through a Jewish lens. What that means, precisely, is open to interpretation. So too is his art.

He describes his Tanach Series, a 36” by 48” acrylic on canvas, as “a heady mix of expressionism and pop art. Adam and Eve sip a Coke under a tree labeled “Apple” as God expels the pair, and their children are forced to work.”

One of the exhibit’s missions is to show commonalities across religious and national boundaries in a dangerously polarized world by focusing on the universal theme of genesis.

“This is urgent,” said Silverstein. “No time more so than now. We have to understand each other.”

One narrative that seemed to have special resonance in the exhibit was a divine creator making the universe and humankind out of nothing as a parable for creativity, the curators suggested.

However, there were some cultural distinctions. While hand-drawn calligraphy and letters exist in the three Abrahamic religions, the Islamic and some of the Jewish artists employed calligraphy as the sole or primary means of artistic expression. The letters created the image. The Muslim artists did not depict the deity in any work in the exhibition, though letters and flowers (examples of God’s work) were drawn, suggesting the divine presence.

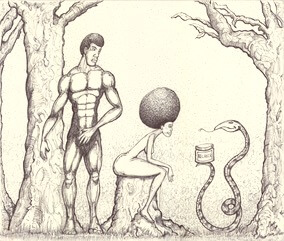

Various artists in the exhibit examine Genesis through political, existential or environmental lenses. The First Deception, by African American artist Jason Thomas, features a Black Adam and Eve. The snake is offering Eve hair straightener. In Eve: Door to Heaven, Christian artist Michele Arnold Paine paints a resigned, isolated, contemporary Eve, almost evoking an Edward Hopper figure, facing a closed door. In Pearls/God Nourishes the Earth with Her Tears, Jewish artist Quimetta Perle presents God as a woman crying. The tears are depicted with exquisite beads.

“Is she crying out of sadness for human beings or is it tears of joy?” Silverstein asked rhetorically.

McBee saw an ecological theme: “She cries because the earth needs her tears to grow. We see her tears falling onto the earth and flowers emerging.”

Silverstein highlighted the cross-cultural elements within some works. For example, in Amistad: A Slave Ship for a New Century, Siona Benjamin, an Indian Jew born in Israel, depicts the historical slave ship Amistad. Only here, the main character is a defiant, arguably a grotesque Lilith, Adam’s first wife turned demon in the Jewish tradition. But in today’s lore Lilith has become a symbol of feminism, empowerment, and, in this context, revolution.

“The complex work addressed the artistic tradition of many faiths and cultures,” Silverstein said. “Lilith is of traditional Jewish interest. The gilded wooden tripartite structure recalls medieval altar pieces as part of Christian tradition. The painted figures recall Islamic miniatures of Persian and Mughal origin as well as Hindu painting. We are moving the conversation forward. There are profound dialogues between traditions.”

“The whole exhibit pushes the envelope,” added McBee.

Verwer says the response to the exhibit has been profoundly positive among the viewers, the artists themselves and especially the curator-artists.

“It made me aware of how ideas can be in conversation and can say the same thing in different ways or different things entirely and still be respectful,” said Silverstein. “It reaffirmed my belief that the choice of content, the creation narratives, still has much to say in the modern world.”

“The incredible diversity of images and approaches to the creation narrative made me realize there was a vibrant contemporary visual culture based on religious texts in the 21st century,” said McBee. “Additionally, the focus of the show made me reexamine the dynamic and positive role of the female in the Eve and Adam narrative.”

“I was thrilled to engage with so many artists of different backgrounds,” Verwer told me. “To see the many different approaches to the same thing was an eye-opener. Seeing my artwork in the context of this exhibition strengthened my identity as a Jewish artist.”

The exhibit Genesis, from Something to Nothing runs through July 30 at the Jewish Theological Seminary. The exhibits at the Interchurch Center and Riverside Church have already completed their run. Works from all three venues can be viewed online. Other pieces that were not displayed can be viewed here.