One of the most important Jewish artists of his generation was born 100 years ago — can you recognize him?

He was a World War II hero and the consummate practitioner of his art, but out of costume, he may not look familiar

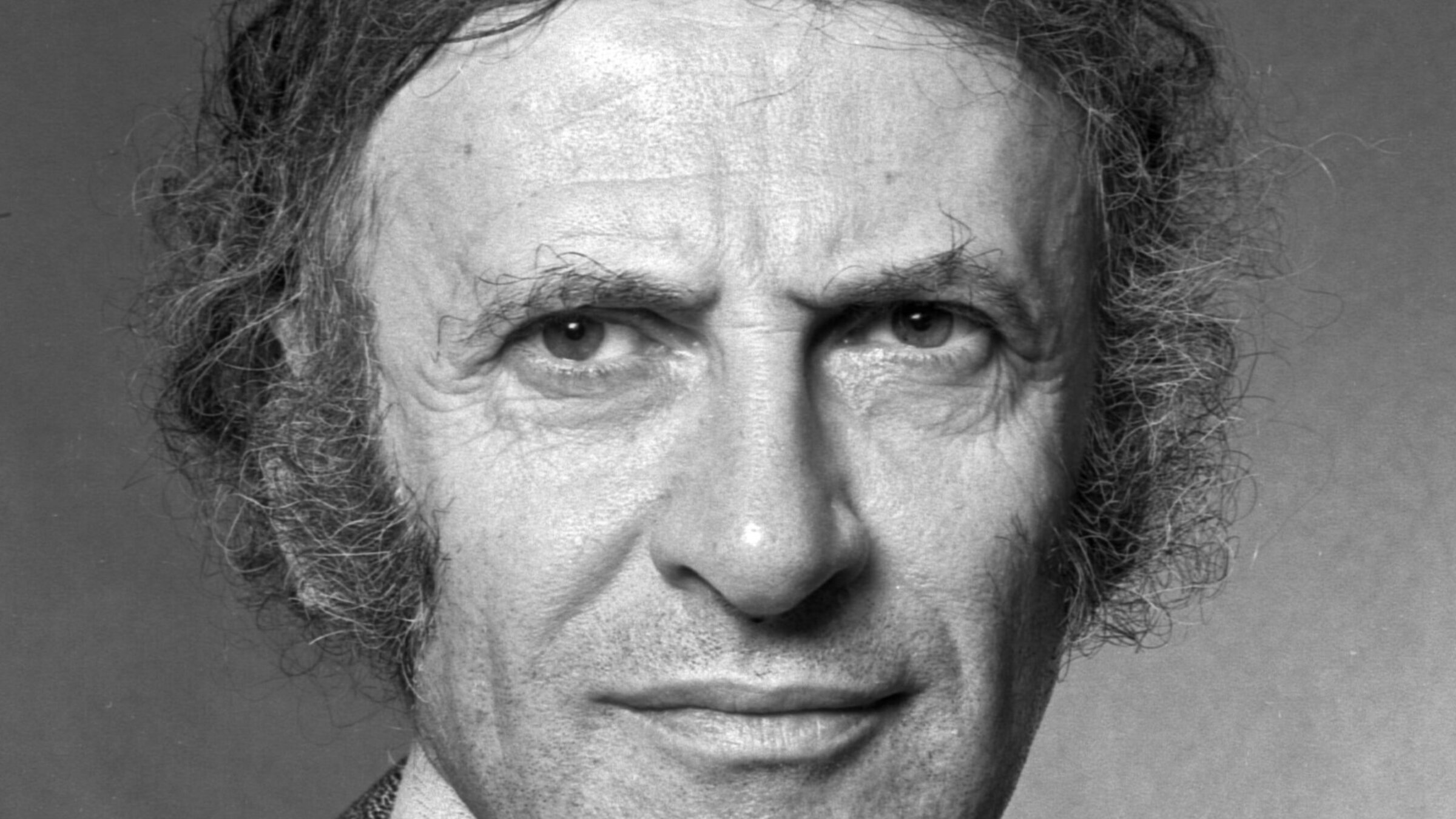

Marcel Marceau in New York, 1973. Photo by Getty Images

This year marks the centenary of French Jewish mime Marcel Marceau, whose Yiddishkeit in performance has until recently been clouded by a certain elusiveness.

Stephen Whitfield’s American Space, Jewish Time explores the paradox of how Jewish identity can be immediately discerned even in nonverbal performers such as Marceau or Harpo Marx.

The theater historian Edna Nahshon chose a portrait of Marceau to adorn the cover of her Jews and Theater in an Intercultural Context, asserting that Marceau’s artistry was “grounded in his uniquely Jewish experience,” alluding to Marceau’s involvement in the French Resistance and the quasi-mystical silence of his stage presence.

Marceau’s activities in the Resistance included using mime to teach the Jewish children he was smuggling out of France how to communicate silently. These actions became widely known after he gave a speech accepting the Raoul Wallenberg Medal in 2001.

At the time, Marceau revealed that he opted for mime as a silent response to wartime tragedies, including the murder of his father at Auschwitz. So although such beloved routines as “The Cage,” “Walking Against the Wind” and “The Mask Maker,” as well as “Youth, Maturity, Old Age and Death,” were not overtly Jewish, a subliminal or subconscious issue of identity might have been at play.

Marceau, born Mangel, of Romanian and Polish Jewish origin, had previously only given fans an inkling of his heroism during World War II. In a 1968 interview with the Kenyon Review, he mentioned after noting his father’s fate: “I helped smuggle children into Switzerland. I was in the Resistance — and the liberation of Paris.”

Marceau added that a tour to Israel two months before the outbreak of the Six Day War made him once again admire the “ancient race” and “old cultural heritage” of Judaism.

In June 2023, the French Jewish director Isy Morgensztern gave a lecture in Paris on subliminal Judaism in the work of Jewish theater creators, placing Marceau alongside other talents whose Judaism may not have explicitly appeared in their art. Among them: Julian Beck and Judith Malina of the Living Theater, Harold Pinter, and France’s Ariane Mnouchkine.

Indeed, Marceau’s only stage work that referred directly to Jewish experience, “Bip Remembers,” placed his stage alter ego in a context of World War II battles and deportation. Although Marceau participated in a 1947 production in Paris of Franz Kafka’s The Trial, he was not the creator of that show.

One year after the Wallenberg Prize event, Marceau demurred to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that Bip was “not a Jewish character.” Although he claimed to “respect” the “history and suffering” of the Jewish people, he had universal aspirations for his art. That said, the fact that he was “born a Jew and was in the underground” influenced his work, he said. Marceau’s artistic ambitions ostensibly transcended religion.

Further complicating the picture are the recollections of Marceau’s cousin the Georges Loinger, who died in 2018 at age 108. Loinger, a leader of the French Jewish Resistance, admitted that the tragic emotions in Marceau’s pantomimes derived from the death of his father. Yet Loinger told The Jerusalem Post that, while the teenaged Marceau risked his life on some missions and forged papers to help Jews and others evade Nazi surveillance, he wasn’t a full-time Resistance fighter.

As historian Daniel Lee implies in Pétain’s Jewish Children, Marceau’s Resistance involvement may have been less sustained than that of his friend, the French Jewish photographer Étienne Bertrand Weill, or indeed even of an older brother who was more committed to the cause.

My own encounter with Marceau as an interviewer some 30 years ago at the Espace Pierre Cardin, a centrally located if threadbare Paris performance venue, reinforced these impressions. Seemingly quite fatigued by supporting a theatrical company, he skirted the topic of wartime derring-do and seemed to prefer to rely on ready-made, already prepared formulaic answers, regardless of the question.

The 2020 film Resistance, in which Jesse Eisenberg starred as Marcel Marceau as a combat superhero who personally faces down the Nazi Klaus Barbie, inspired a public rebuke from Marceau’s daughters for its inaccuracy. In real life, Marceau never confronted Barbie and his Resistance activity was nonviolent.

Marceau’s daughters recently published a brief autobiographical text by their father, written sometime before his untimely death at a French racetrack on Yom Kippur in 2007. The memoir covers the first 29 years of his life, reaffirming Marceau’s avowal that his choice of silence was inspired by the brutal disappearance of his father.

Marceau’s book also evokes his idyllic Jewish childhood in Alsace, before the rise of antisemitism and the German invasion, which caused his family to flee to West-Central France.

In a rare verbal gesture, Marceau renamed himself during wartime in honor of an anti-dictatorial French Revolutionary War general lauded in Victor Hugo’s poetry collection The Castigations. Hugo praised the valor of rebellious violence against tyranny, whatever the era. Hugo’s stirring revolutionary call clearly motivated Marceau: “Volunteers, die to save all people, your brothers!”

Marceau, who spent his last years ailing and no longer able to tour, died in debt. To settle his estate in 2009, a French court ordered the public auction of his belongings, some of which were purchased by his friends and admirers, hoping to convince the French Ministry of Culture that a proposed museum of mime, a longtime French art, would be an appropriate place to display them. This plan has yet to win bureaucratic support in France.

Marceau’s niece, the famed Israeli singer Yardena Arazi, expressed concern that mime might languish as an art form without his presence to champion it. To help prevent this, Jewish fans of Marceau might recognize that while by far the most celebrated Jewish mime of the modern era, Marceau was not the only one. Colleagues and students, especially in Israel, have included Yeshayahu “Shaike” Goldstein-Ophir, Samy Molcho, Yoram Boker, Yisrael Gurion, Ofer Blum, and Hanoch Rosènn.

To celebrate his centenary, Marcel Marceau may best be commemorated by recalling the words of former Grand Rabbi of France René-Samuel Sirat, who read the Kaddish at his burial, informing the attendees that Marceau “always defined himself as a citizen of the world, with Jewish roots.”