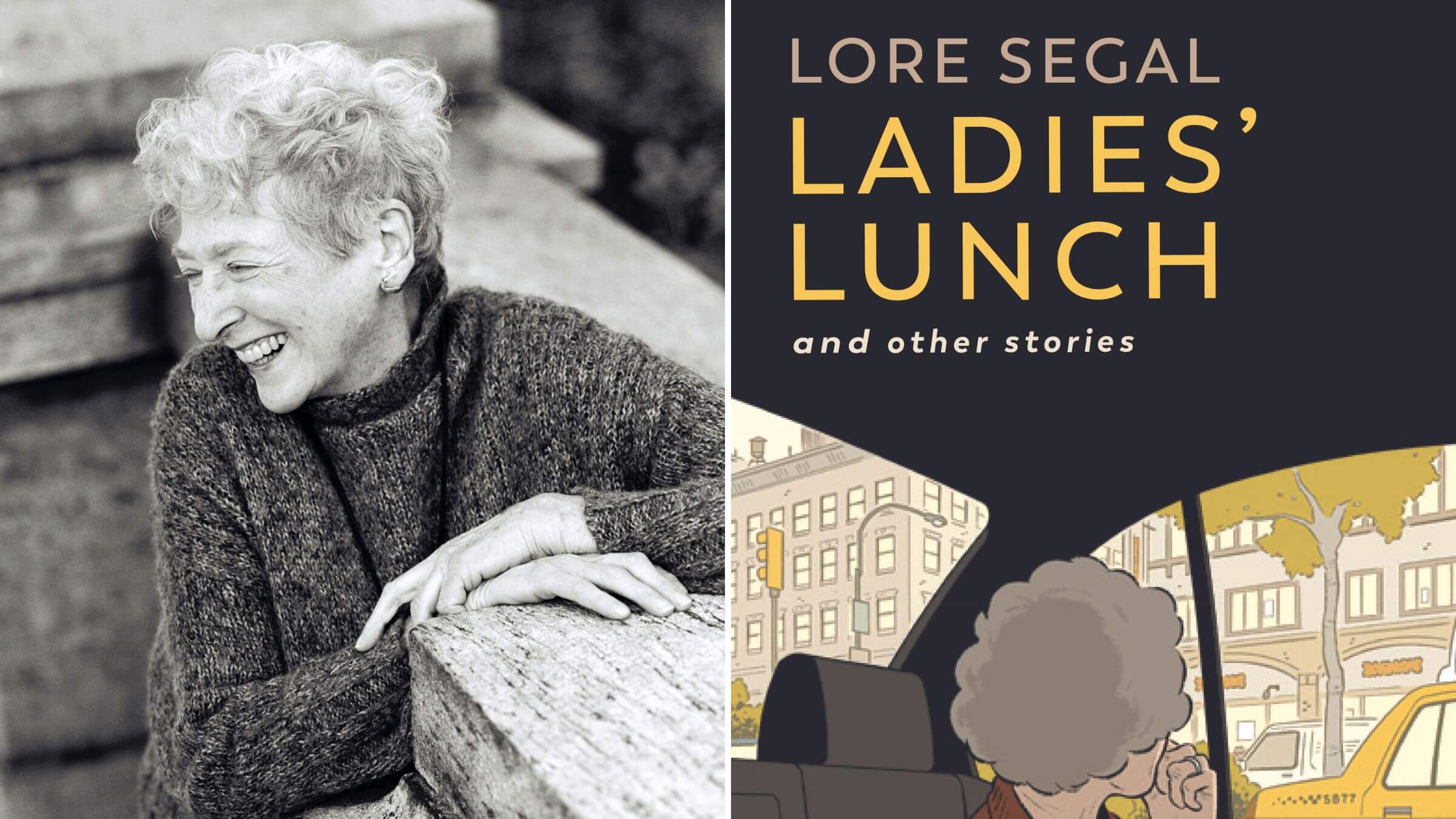

Haunted by the Kindertransport and COVID-19, this 95-year-old Jewish writer chronicles a changing world — over lunch

Lore Segal’s latest collection, ‘Ladies’ Lunch,’ follows a quirky (and cranky) group of aging New Yorkers through four decades of get-togethers

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

When Lore Segal first started writing, she had a single purpose in mind. Soon after arriving in England in 1938 on the Kindertransport from Nazi-occupied Vienna, the 10-year-old girl launched a letter-writing campaign to get her parents out too. It worked: Within a year, they were reunited. Now 95, Segal has four novels and dozens of short stories to her name and is one of the oldest active American writers. Though her stories may be fictional, they’re often informed by her own life and infused with the urgency of that first, all-important project.

Her latest collection, Ladies’ Lunch and Other Stories, features a group of five erudite, sharp-witted nonagenarians, all longtime New Yorkers, who have maintained a regular — if chaotic — schedule of get-togethers for the past 40 years. “We are the people to whom we tell our stories,” one reminds the group, outlining a project that can only grow more pressing as memories fade and death — or worse, the nursing home — threatens.

Segal’s great themes are friendship, family, and growing old, but the memory of the Holocaust often looms over these seemingly domestic concerns. Sometimes clocking in at fewer than 1,000 words, her stories are minimalist in style but monumental in feeling, capturing the rich yet ephemeral texture of ordinary lives haunted by a catastrophic past. And as the title suggests, she also sets out to rescue the concept of “ladies who lunch” — not just from the Sondheim song that popularized the phrase, but from the derision with which many male writers and younger people have treated groups of old women.

Segal began publishing stories in the Ladies’ Lunch series in 2007. The newly issued collection, which combines new and previous work, brings the indefatigable ladies into the pandemic era. Her stripped-to-the-bone style in these pieces conveys the intensity of writing toward the end of life: Shorn of fancy words and writerly affectation, her paragraphs sometimes approach the starkness of Greek tragedy. Adjectives, it would seem, are best left to younger writers. She uses them sparingly, parceling them out like WWII rations.

In “Soft Sculpture,” a woman named Ilka (a recurring character in Segal’s work who is sometimes a stand-in for the author) takes a walk with her friend Bridget and recalls a childhood birthday that was memorable for two reasons: She received a pet turtle as a gift, and Nazi storm troopers evicted her family from their Vienna apartment.

Naturally, Bridget wants to know what happens next. But Ilka can’t quite recall. She can only remember seemingly irrelevant details: the bathroom with a wall-mounted gas heater and tub where her mother set the turtle; her father’s razor and leather strop; and, in a twist that brings the story closer to the present, a turtle hand puppet she bought for her own children years later, after she had resettled in New York.

Ilka’s forgetfulness might signal that memory loss is coming for her, as it has for so many of her peers. She may be unable, even after so many years, to discuss her childhood. Perhaps Segal is simply drawn to the sensory qualities of daily life, so much so that the sounds, shapes and colors of Vienna “before Hitler” can outlast the trauma of exile.

An only child born in 1928 to upper-middle-class Jewish parents, Segal made her name by turning her eventful life into memoir and autobiographical fiction. Her 1964 debut novel, Other People’s Homes, was based on her experiences living in five foster homes after arriving in Great Britain as part of the effort to rescue children from Nazi-occupied territory. She has since written four other works of fiction, including the Pulitzer-nominated story collection Shakespeare’s Kitchen, and a slew of essays, children’s books and translations.

In her late work, the inexorable process of growing old threatens a different kind of annihilation than the Holocaust. In the story “Ladies’ Zoom,” the women struggle to recall words that have simply dropped out of their minds. “What do they call the kind of — the — what do you call the living for old people that Lotte’s son moved her into,” Bessie says, referring to a friend who has died. Conversations like these tell the reader that even as the ladies blithely discuss Lotte’s fate, they’re keenly aware of their own limitations.

Naturally, the ladies lunch virtually during the coronavirus pandemic, when “their several children’s anxieties” prevent them from meeting in person. And naturally, being a jousting bunch, they quarrel about the technology. In these newest stories, Segal gently satirizes the ladies’ technological incompetence while emphasizing the intellectual acumen they’ve retained despite the many indignities of lockdown and old age. When one character grumbles that they’re talking “to little movies of ourselves instead of with each other,” another defends “this blessed technology,” which allows her to carry around the entire works of Jane Austen and “make the letters large enough to read.”

The appointed topic of discussion at the meeting — because every lunch needs an agenda — is the impossibility of leaving things in order for one’s children when one dies. That’s because in order to do so, they would have to get rid of old papers, old pictures, even decades-old address books, which they can’t bear to do. “Dead or alive,” one says, “it turns out one cannot throw people away.”

Ten years ago, after Philip Roth and Alice Munro announced they had stopped writing fiction, an interviewer asked Segal if she planned to do the same. Her reply? “What would I do with my hands, mornings from 8 to 1? And won’t some thing that I think, or see, or hear turn itself into words?”

Reading Ladies’ Lunch, one can only be thankful that Segal has not “thrown away” her people or her memories, which have given us this indispensable road map of our final journey.