A new golem is born with a new mission — protecting vulnerable communities and cultural history

Michael Rakowitz creates monuments from the destruction of other monuments

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

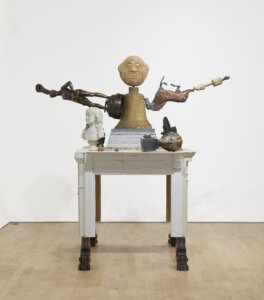

An “American Golem” looks over the rest of the gallery with a quizzical expression. A three-dimensional pastiche — his head a copy of a Babylonian fired-clay mask of the first monster, Humbaba, the original of which is on display at the British Museum along with hundreds of relics seized from ancient cultures — this golem is the work of Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz, whose work focuses on reconstructing and redefining destructed cultural works.

“Toppling monuments seems like something that happens only in faraway places,” Erin L. Thompson wrote in Smashing Statues, The Rise and Fall of America’s Public Monuments, a book Rakowitz read while preparing this project. “In reality, monuments go up whenever a society changes and they fall whenever a society changes again in America and anywhere else.”

In American Golem (2022), on display as part of Rakowitz’s solo exhibition The Monument, The Monster, and The Manquette, the artist has created a monument from fragments of other monuments. Its body is a wooden mold from a bell factory which cast bells that were melted down to make cannons for the Confederate army. One arm is a zinc weather vane of a horse made by a company that fabricated a memorial for the North after the Civil War; the other comes from a Robert E. Lee monument.

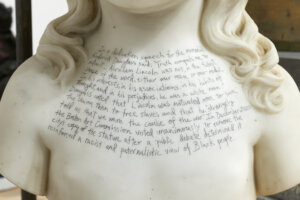

American Golem is not an erasure; instead it is a palimpsest in which Rakowitz’s scrawled words force us to see all the layers he has used. “Monument is derived from the Latin verb monere, meaning to remind, advise, warn,” Rakowitz has written on the pedestal of American Golem. “Also derived from monere: demonstrate, remonstrate, monster.” The artist plays with all these meanings here.

Composed of found antique objects, granite, and wood on a metal base, Rakowitz has annotated the various assembled parts of American Golem, writing onto the objects their origin and history.

On several of the objects, he calls attention to the source of the materials.

On the base on the fallen head he writes, “Sphalerite, the primary ore of zinc, used to make many of the Union and Confederate monuments sold by the Monumental Bronze Co. Extracted from a mine in Galena K.S. on occupied land of the Osage people.”

“Yale marble from Colorado, extracted from occupied land of the Ute people,” he writes on a piece of marble. “Used by architect Henry Bacon for the Lincoln Memorial’s columns and structure.”

“In Judaism, a golem is a beast made from clay, which is activated by the Hebrew word for truth, emet, and defends vulnerable communities,” Rakowitz told Thompson in a 2022 interview. “These stories originated in times of pogroms in cities like Prague — the golem is almost like the first superhero.”

In Rakowitz’s work, scrawled words on the objects function like the word emet on the golem’s forehead, activating memory to protect vulnerable communities by preserving their cultural history.

Writing on objects isn’t new for Rakowitz. In 2015, he addressed the Armenian genocide in The flesh is yours, the bones are ours at the Istanbul Biennial, creating new friezes and recasting old ones that were demolished by protesters in the Gezi Park protests in Turkey.

“These plaster decorations, the traces of Armenian fingers and hands, have borne silent witness to the traumatic stories of the city’s Armenian population,” he wrote on his artist’s webpage. In an effort to resist the silencing of these stories, he added his handwriting to accompany objects in that installation.

“Mine is a desire to suture, to mend the breach, all without erasing the wound,” he said. “I insist on the reappearance of what has disappeared being a way of also keeping the wound visible and felt.”

In a 2018 work, using 10,500 Iraqi date cans, Rakowitz recreated in Trafalgar Square the Lamassu, an Assyrian deity in the form of a winged bull that had stood guard at the entrance to the Nergal Gate of Nineveh from 700 B.C.E. until February 2015 when the Islamic State destroyed it.

“I understand these projects not as rebuilding or reconstructing but as reappearing,” he said in an interview. “As a child of Jewish parents who were both born in 1945, in the aftermath of the Second World War, I learned from a very young age about the book burnings that preceded the burning of bodies during the Holocaust.

“Destruction of cultural works often precedes the destruction of the people who live alongside them,” he added. “You can’t reconstruct the lives that have been destroyed, maimed and interrupted alongside ravaged archaeological ruins. Reappearance, on the other hand, is a recurring motif in my work because disappearance recurs throughout history.”

In Monuments in Solia 1 (2022), Rakowitz has written at the bottom, “In 2015, as part of Ukraine’s de-communication laws, a statue of Lenin in Odessa was transformed by artist Oleksanr Milor to become Darth Vader. His helmet emits free WiFi.” The drawing shows the original statue in a faded etching behind the current Darth Vader statue, drawn with darker pencil. In essence, Milor’s transformation is a constructive way to critique and change a monument, rather than destroy it.

In Rakowitz’s Behemoth (2022), a large inflatable structure dominates the room. A monument covered in black tarp, it’s in a continuous cycle of movement, of rising then falling: It inflates into an erect position, pauses, then deflates, becoming completely flaccid, then the cycle repeats, reminding us that nothing is permanent — a monument erected one day by a group in power will one day be torn down.

These works act to resist cultural amnesia and erasure. They are a way to keep wounds visible and felt. Rakowitz’s project argues for preserving layers of the past, for creating palimpsests. His art reminds, advises, warns us against our instinct for destroying cultural works in the name of dominance and power.

The exhibit The Monument, The Monster, and The Manquette runs at the Jane Lombard Gallery in New York through Oct. 21.

Correction: An earlier version of this story included a typo making it unclear how many date cans were used in Lamassu. It was 10,500.