Can art help us process the atrocities committed by Hamas on Oct. 7?

In different ways and in different eras, the work of three artists imagines the unimaginable

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Though the horrors of the Hamas attacks on Israel on Oct. 7 defy imagination, the work of three very different artists — two who survived the Holocaust, one who has posted a new set of watercolors on social media — provide solace and give voice to those trying to make sense of the atrocities.

The work of Yonia Fain, who died at 100 in 2013, is represented in an unassuming exhibit at the James Gallery at the CUNY Graduate Center. Fain was born in Ukraine, fled Bolshevik Russia as a young child and moved to Vilnius, Poland, then when the Nazis invaded Poland, escaped with his first wife to Japan (after being conscripted into the Russian army) where they spent the remainder of World War II in the Shanghai Ghetto.

After the war, he moved with his wife to Mexico, where he connected with Diego Rivera, then finally in 1953 emigrated to and settled in New York. In addition to being a painter, he was a Yiddish poet, writing five books and serving as president of the Yiddish Pen Society.

Though Fain created his art to process the horrors of the Holocaust, his work also speaks to the anguish we feel in response to Hamas’ barbaric slaughtering of Jews — here is an artist who witnessed such horrors and persevered.

The graphite and ink on paper, “The Night” (1941-1946), in which a dark bulky figure menaces a smaller man, perhaps naked or wearing a white shirt, screaming with a contorted face in fear and anguish, as two men in shadow threaten the victim with long guns, seems like an image straight from the attacks on one of the southern kibbutzim.

In the drawing, “Rage” (1941-1945), Fain’s simple lines etch a headless figure with clenched fists raised up in the air, raging against God, or the lack of God, conveying an emotion that echoes that feeling of incomprehension, anger, numbness at not comprehending how God could allow men to commit such an attack. Other works in the exhibit — The Scream” (1997) and “Untitled (Dying Horse)” also embody this expressive emotion of despair, of a scream that no one hears: It’s cathartic to see these screams expressed loudly on canvas when one feels numb, unable to express one’s sorrow and pain.

Looking Bak

“Bak Looks Back,” which recently closed at the Pucker Gallery in Boston, featured works of the 90-year-old painter Samuel Bak, a number of which had never been exhibited before, including some from when he was a young boy of 13 and 14.

This look back at 77 years of Bak’s paintings, a small sampling of his 10,000 works, showcased his early experimentation with abstraction and futurism, and then his development in the mid-1960’s of his unique visual vocabulary and language which has allowed him to process his own memory of the Holocaust and his questioning of the human condition, the evil that humans are capable of committing against each other.

Bak was born in Vilna in 1933. At nine, his work was exhibited in the Ghetto of Vilna where he lived with his family. He and his mother survived the Holocaust, but his father and four grandparents were murdered by the Nazis. After the war, he fled with his mother to the Landsberg Displaced Persons Camp where he lived for three years and heard first-hand about survivors’ experiences. In 1948, he and his mother emigrated to Israel. In 1956, he went to Paris to continue his arts education, in 1959 to Rome. He settled with his wife in the Boston area in 1993, becoming an American citizen.

Despite the fact that they depict the atrocities of the Holocaust, Bak’s works are never gory. Instead, he creates a visual language of symbols, in which common elements recur. His favorite fruit, the pear, evokes the shape of the womb; it resembles life, fertility and the human figure. Other repeated symbols include the egg, which represents the fragility of life, as well as the chessboard and chess pieces.

Through the iteration of symbols, we see Bak’s development of a metaphoric language. Bak paints teddy bears, disfigured and fractured, as in “Teddy Interrupted” (2022). Fragmented pears reflect a fractured universe and fractured human bodies. Bak often paints the dove, but not the flying white dove of peace or hope. Here, in “Voyage in Time” (1975-6); this bird is still, grounded. Does that mean hope or escape is futile?

Bak’s paintings evoke Magritte’s; he paints objects in a realistic way in order to evoke the strangeness of reality, of a world gone mad in which men willfully destroy men, women and children. In contrast to the emotionality of Fain’s work, these paintings are intellectual puzzles, a way to deal with the trauma he witnessed and heard about as a young boy in the DP camp.

As is the case with Fain, there is not much solace to be found here. Bak is a painter of questions, a starter of thought-provoking conversations. In one painting in the permanent exhibition of the gallery, “Ghetto of Jewish History,” there is a Jewish star in the rubble of destroyed buildings — is it being unearthed or concealed?

Bernie Pucker, gallery owner and long-term friend of Bak, said that many people, largely Americans, asked Bak, where was the hope, the consolation in his work? In response, Bak painted “With a Clear Background” (2012), a still life with each of the letters of the word “hope” an object in the still life: the letter “e” of the word dissects a pear, slicing, fragmenting it. “Ah, you want hope?” the painting seems to ask tauntingly, “here it is as a weapon, severing a pear.”

Witnessing Bak’s body of work, one senses that we can never rid ourselves of the past, of our memories, individual and collective, of suffering and trauma. But there is a playful irony that runs through the work, and this irony and wit is itself evidence of the power of human intelligence and resilience in the face of despair.

Objects left behind

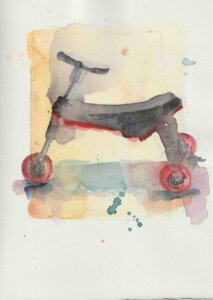

Whereas Bak’s paintings are often puzzles to unpack, Israeli-American artist Andi Arnovitz, who lives in Jerusalem, is able to move the viewer with the sheer simplicity of her painting. Arnovitz’s series of soft watercolors, called “October 7, 2023,” shared via Instagram and Facebook, depict the objects left behind that seemingly ordinary Shabbat morning October 7 when families were waking up.

In each, she depicts an object to show how ordinary life on the kibbutzim in the Gaza envelope was interrupted, irrevocably. She studied all the photographs she could of the destruction in the kibbutzim in the south.

“It struck me when I saw them” she said, “about how alike we all are. . .and I was so incredibly moved by the sight of the child’s slipper, the diaper, the half drunk pot of coffee, the newspaper, the cat food bowl. I kept coming back to that moment Saturday morning when everything was fine, and then, in a split second, nothing was fine. Life interrupted. Ripped. Wounded.”

Arnovitz is trying to paint one watercolor a day right now; as she is helping to take care of grandchildren with one son-in-law who lost an eye in Gaza and returned home, and four other sons and sons–in-law in combat, she “can only do small pieces that take me short bursts of time.” The paintings’ quiet intimacy reflects the intimacy of these barbaric attacks, inside people’s homes, as they slept or woke up for the day.

A stark contrast to the images of Bak’s complicated metaphysical world, and to the heightened emotionality of Fain’s, it is enough to see a watercolor of a coffee press, filled with coffee that morning, yet never drunk, or a tricycle, forever cast aside, to bring us to tears. These quiet works embody our communal pain.