Leonard Bernstein and Taylor Swift: Both musical geniuses, but only one movie captures the spirit of their artistry

Back-to-back screenings of ‘The Eras Tour’ and ‘Maestro’ yield surprising insights into the enchantments of fame

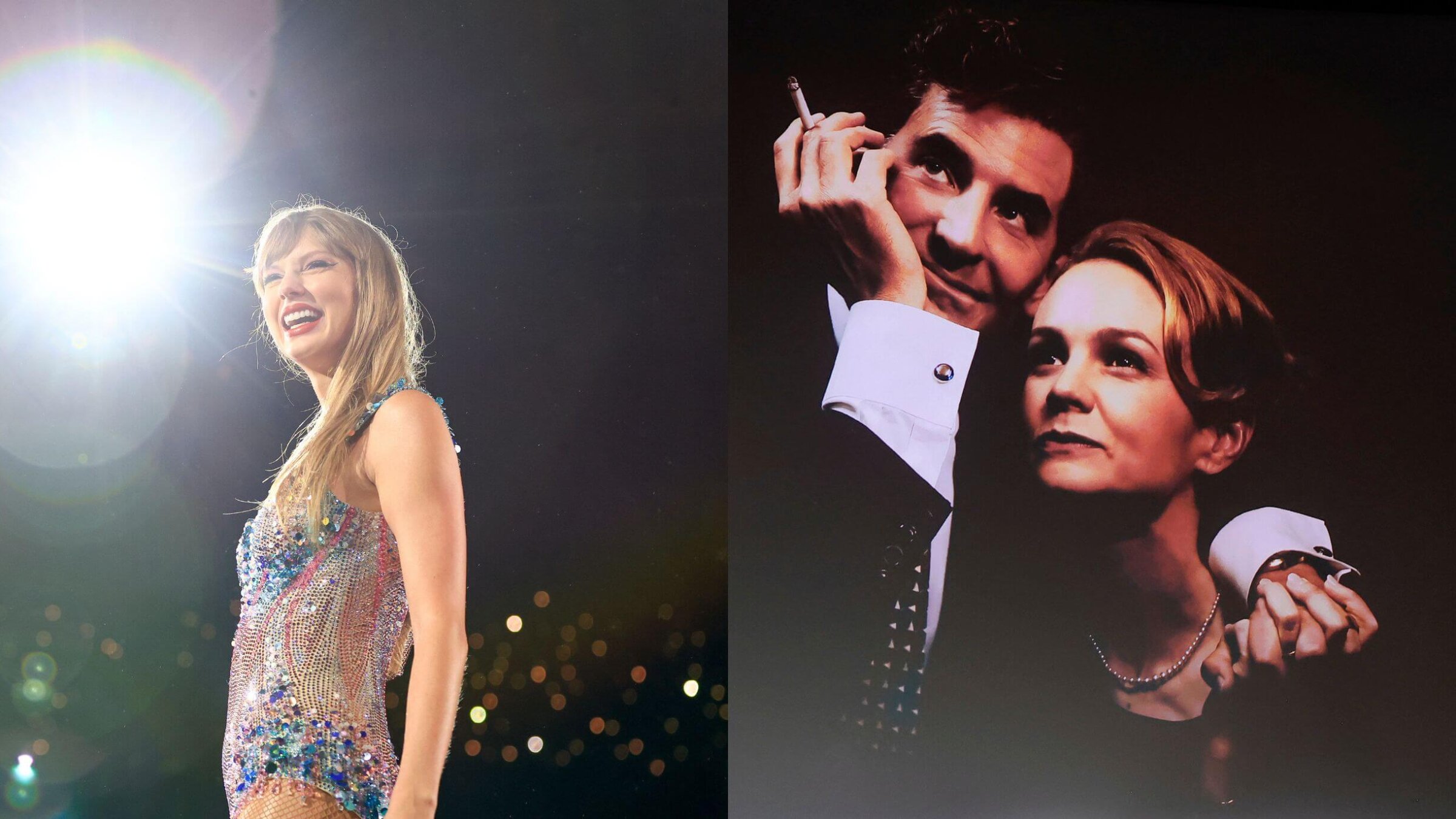

Two late-2023 movies, Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour and Bradley Cooper’s Maestro, explore the seductive aura of genius. Photo by Buda Mendes/TAS23/Getty Images and Emma McIntyre/Getty Images for Netflix

There he is: Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein, sweating his way through conducting a Gustav Mahler symphony in the most entrancing scene in Maestro, Cooper’s sophomore directorial feature.

And there she is: Taylor Swift, marching through a 3-hour setlist in Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour, unflagging in the L.A. summer heat.

Two buzzy late-2023 releases about contemporary musical giants who reshaped their industry in their image. Two projects conceived by artists determined to make a statement about the painstaking effort behind creative genius.

And two films that, on one chaos-ridden late-November Wednesday, I saw back-to-back.

What I learned: Sometimes, the art really is more interesting than the artist — or, at least, the most interesting way of getting to know them.

That’s not to say that Bernstein is uninteresting, Cooper untalented, or Maestro unsatisfying. But the surprising juxtaposition of Cooper’s highly stylized Oscar hopeful with Swift’s skillfully assembled but straightforward concert flick helps demonstrate some of the shortcomings of the biopic as a genre when it comes to capturing the indescribable thing about some artists that makes audiences crave more.

Not just more art. More persona, more drama, more tidbits of thrilling information, more — as Swift puts it in her song “Bejeweled” — shimmer.

In many ways, the appeals of Bernstein and Swift run counter to one another. Him: Jewish, chic in a disorganized and spontaneous way, brimming with passion — sometimes, if not frequently, to his personal detriment — and a mainstay of New York’s intellectual cultural elite. Her: Raised on a Christmas tree farm, so polished and poised as to sometimes seem calculating, intensely self-aware, a darling of pop culture sometimes dismissed, through much of her early career, as not being a serious musical thinker.

But both are the kind of artist whose public allure becomes its own kind of art, a metatext into which all of their accomplishments feed.

Maestro is both obvious and coy about that feature of Bernstein’s life. Aside from that one tremendous Mahler centerpiece, there are only a few scenes focused on Bernstein’s musical pursuits. It’s clear that the Bernstein mythos, rather than the Bernstein catalog, is the film’s reason for existence.

That’s made particularly apparent by the film’s focus on Bernstein’s marriage to Felicia Montealegre (Carrie Mulligan). Films that aspire to distill an artist’s inner life habitually turn to that artist’s relationships with their muses, and while the extent to which Montealegre filled that role for Bernstein is unclear — including in Maestro, in which the typically excellent Mulligan isn’t given nearly enough to do — her centrality to the movie is a clear sign of its intentions. It’s going to excavate its subject’s aura, and give audiences something human about him to hang onto.

The audience is supposed to already know and care about Bernstein. If he doesn’t already exist in their minds as a genius, they’re unlikely to leave the movie with a clear understanding of why he was considered one. The humanity is there, although it’s uneven; Cooper’s Bernstein comes across as a frenetic, sentimental sketch of a great man. But a clear sense of why it might be significant to understand the humanity of this particular man, in context of his particular accomplishments, never quite arrives.

Contrast that confusion with the simple clarity of The Eras Tour, directed by Sam Wrench. It’s all about Swift’s aura, because it’s all about Swift’s music. A 30-something cousin I went with walked in claiming to not be a Swift fan — although she knew the lyrics to 99% of the songs, so, OK girl — and told me later that night that she left it “really enamored.”

The film gives very few hints as to Swift’s internal life, outside of the many that appear to exist in her music. At the few points when she introduces her songs, she’s speaking to a stadium audience of thousands. There’s a lovely, natural feeling to those interactions, but she’s not saying anything that hasn’t been rehearsed.

Yet there’s an immediacy to the way she sings through her well-known catalog, making the overplayed seem fresh, and the most famous person in the world seem like an intimate friend. I’ve listened to the 10-minute version of “All Too Well” more times than I care to relate, but watching Swift perform it, alone onstage, with those screaming thousands hushed by the power of the moment, I teared up. It felt so raw and present. The world outside the lyrics disappeared.

That, really, is what the issue of a celebrity’s aura is all about. It’s not the fleeting sense of a fascinating person, there behind the art, whom audiences genuinely wish to know and love. It’s about how much that artist’s presence, even just as an idea, transports audiences to a different plane.

Yes, when there is something we cannot explain about why and how we have been moved by someone, it’s natural to seek information that might help us understand. It’s like lifting the lid of a piano, to watch the hammers hit the strings.

Perhaps, if we saw the precise pattern of notes Leonard Bernstein’s marriage left on his soul, the work he composed and conducted would finally begin to feel a bit more real, and not like an extraordinary, profound enigma. Perhaps if we knew all the intimate details of all of Taylor Swift’s heartbreaks, we’d finally see behind the magic trick of how she can make us reevaluate and move on from our own.

But it’s a tall order for any artist to replicate, let alone find something new in, another’s magic trick. Maestro might effectively mimic some parts of Bernstein’s mercurial appeal, but it is not magic in the way that Bernstein himself somehow was, because it it can’t get close enough to the source of his great fascination — his music. Any one of the many episodes of his Young People’s Concerts viewable on YouTube has more insight, albeit with less pizazz.

And so, the magic of The Eras Tour, which lets Swift sing us away from ourselves, and leave wondering how she did it.

My cousin had it right. “Enamor” comes from the French for “to fall in love.” To be truly in love is an act of miraculous suspension. You feel as if you have connected with the other person at the point of absolute essence — that you know their purest self, even as your awareness of their sour points tries to pull you out of the trance.

A great artist shows something of their essence through their art. They may not even understand how they’ve done it, but there it is: a soul, somehow, on display. And as in love, when their human flaws become the focus, the magic disappears.