Hippie, hero, traitor, spy — the baffling legacy of Jonathan Pollard

A documentary series tries to shed light on the many contradictions of the man who spied on America for Israel

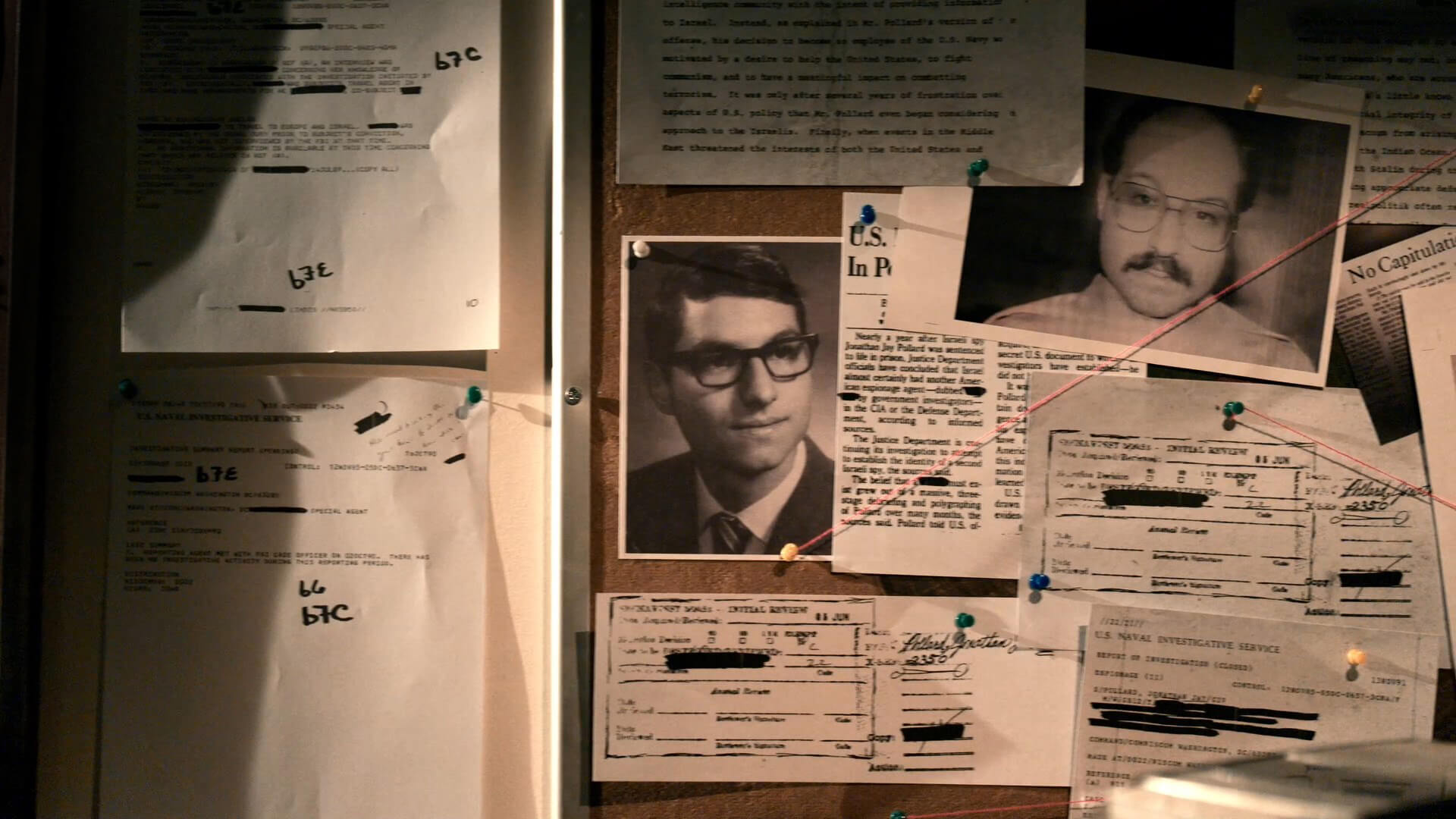

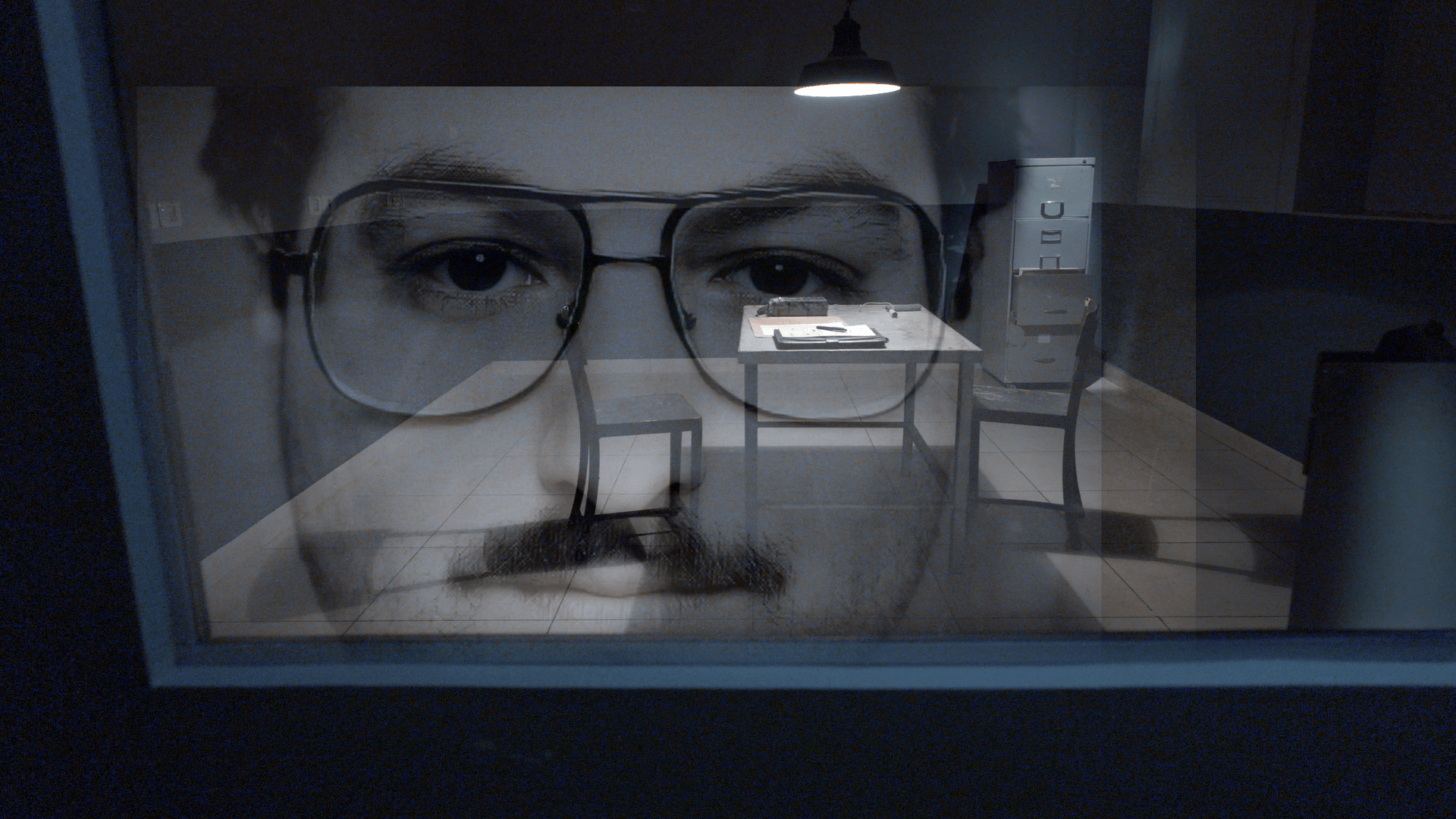

Throughout his life, a new documentary informs us, Pollard was obsessed with excelling and obtaining accolades. Courtesy of ChaiFlicks

The “Pollard Affair,” as it came to be known, was one of the most significant upheavals in the history of American-Israeli government relations. An American Jewish U.S. intelligence officer with a single-minded ambition to save Israel, Jonathan Pollard was convicted in 1985 of selling closely guarded U.S. secrets and highly classified intelligence material to the Jewish state. Pollard spent almost 30 years behind bars before he was released to Israel in 2015.

Created by veteran investigative filmmaker Omri Assenheim and directed by Gilad Tokatly and Shany Haziza, Pollard, a four-part documentary series, is an intriguing, at moments jaw-dropping study in manipulation and incompetence at all levels. Its protagonist, whose story seems to have sprung out of a John le Carré novel, comes off as, depending on your viewpoint, a hero, a villain, a drugged-up wackadoodle, an incorrigible liar, a fantasist or all of the above.

The story also brings to the fore questions about America’s relationship to Israel — and by extension, how Jews respond to fellow Jews who are less than sterling human beings. It’s a timely topic in an era of rampant antisemitism.

Moving back and forth in time and featuring interviews with former American FBI agents, Israeli intelligence members and many other high-ranking government officials, Pollard traces the evolution of the scandal.

Regrettably, Pollard himself was not interviewed for the series, but his persona and convoluted thinking (or, more accurately, non-thinking) are palpably present.

Throughout his life, the documentary informs us, Pollard was obsessed with excelling and obtaining wild accolades. From the outset, he focused on Israel for reasons that can only be surmised. The son of a Holocaust survivor and a professor at Notre Dame, Pollard grew up in the ’60s and ’70s in South Bend, Indiana, a community where antisemitism was openly expressed and Jews were not allowed in the posh social clubs.

His classmates recall him as a bullied nerd. While his fellow students donned long, unkempt tresses and sloppy jeans, he sported close-cropped hair and his shirt was always neatly tucked into his pants. He wore belts and never laughed.

His bar mitzvah and the 1967 War occurred around the same time, which represented a turning point for the 13-year-old whose commitment to Israel was further enhanced by a trip to Dachau.

His fixation with Israel grew exponentially. By high school, he developed a habit of informing his contemporaries and their parents that he was planning to be a spy for Israel, a revelation which elicited giggles and gossip. At Stanford University, where he played strategy war games and smoked marijuana before moving on to harder drugs, he claimed to be working for the Mossad.

He briefly attended law school at Notre Dame followed by a stint at Tufts, dropping out of both programs to apply unsuccessfully for a job at the CIA where a test revealed that he had falsified his academic records and work credentials, and had a history of drug abuse.

He ultimately found work as a low-level analyst at the Naval Intelligence Agency, which apparently never bothered to dig into his past — bureaucratic ineptitude served as a backdrop to much of Pollard’s career.

Pollard managed to infiltrate Heritage Foundation and AIPAC events where he made it his business to meet the various movers and shakers who could advance his career. Along the way he encountered Aviem Sella, a former commander in the Israeli air force who recruited Pollard as a spy. Pollard maintained he had access to top secret documents that could affect Israel’s security.

After watching the documentary twice, I’m still unsure about the hierarchy of players and what precisely their jobs entailed or how involved the Israeli government was in Pollard’s hijinks. Many of the cloak and dagger elements depicted here — including drop-offs, codes and lots of semi-successful subterfuge — are not always clear, entertaining as they may be.

What is transparent is the joy Pollard experienced as he clandestinely lifted top secret documents. For many months he remained undetected and grew cocky, ultimately strolling out the door with the materials visibly in hand.

His substantial earnings as a spy, which made it possible for him to host lavish dinners, only enhanced his larger-than-life self-image. His book-lined apartment boasted thousands of volumes and he wrote detailed biographical sketches on members of his inner circle.

But like any Greek hero whose unhappy fate is predetermined by their fatal flaw, Pollard who was undone by his mushrooming self-confidence. The mid-’80s was a bad time for spies. An estimated 27 were caught, and operatives were on the lookout. Within a year, Pollard’s coworkers, who previously saw him removing documents from the building and had remained silent, felt compelled to speak. They reported him to the authorities and cameras were installed throughout the office to officially catch him in the act.

The third episode, “Doors Locked,” is the most gripping and fun. (Am I allowed to say fun, considering the stakes?) There are below-the-radar meetings, suitcases filled with documents changing hands, and some very real car chases. The music is suspenseful and we are introduced to two great characters, female counterintelligence agents who are as stony-faced, vocally flat, and noncommittal as any stereotypical male secret service agent sprinting alongside the president’s car. Pollard tries to outsmart them, but he’s ultimately out of his depth. In one snippet, his tone flirtatious, he says he’s aware that surveillance cars are flanking his building and that he’s being monitored at all times. Deadpan, they assure him that the agents are in fact bodyguards there to protect him from would-be assassins.

Despite the Keystone Cops-style antics, the story turns dark as the American agents close in on a now-terrified Pollard and his wife, who has unwittingly become entangled in his schemes. Suddenly, Pollard’s handlers and contacts are nowhere to be found. Some have flown out of the country. Others insist they know nothing about spying activities.

In a desperate effort to elude his pursuers, Pollard frantically drives to the Israeli embassy, where he is barred from entry. Stunningly, no contingency plan was in place for Pollard in the event he was caught. Pollard was betrayed and abandoned. But then, perhaps he was always viewed as an exploitable and disposable lightweight.

A media circus erupted in the wake of his capture. It was a humiliating and enraging disaster, a diplomatic catastrophe, all the more so because Israel was a close ally.

In an effort to salvage the diplomatic relationship without losing face, the Americans brokered a deal with the Israelis: If all stolen documents were returned and all participants recounted their espionage activities, they would receive immunity. This agreement did not extend to Pollard.

In theory, the Israelis agreed. In practice, according to all accounts, they were not fully forthcoming. In Pollard, one high-level Israeli player sums up the situation by saying there’s a difference between lying and not revealing the whole truth.

In the end, Pollard received a life sentence for his crime. The documentary never establishes what damage he caused to American security. More importantly, he sold secrets to an ally, whereas spies convicted of handing over sensitive documents to enemy nations were doomed to far less time behind bars. James Olson, the former CIA chief of counterintelligence, says he “does not exclude the possibility that there was antisemitism” at play.

Still, I wish the documentary had told us more about how Main Street gentiles as well as Jews felt about Pollard. Did they even know who he was? Either way, no one was more stunned or beaten in the face of his sentence.

But his story was not over yet. Thirty years down the road he had become a cause célèbre in some circles. In 2015 he was released to Israel. Disembarking from the plane, he got on his hands and knees to kiss the ground. Still a performer, he had morphed into an aging hippie, his straggly gray hair hanging down beneath a yarmulke.

The documentary Pollard is now screening on ChaiFlicks.