Could this be the most meaningful Holocaust memorial in New York?

In Riverside Park, a stone meant to be a placeholder for a grander memorial has become an unlikely gathering place for Bundist Holocaust survivors and their descendants

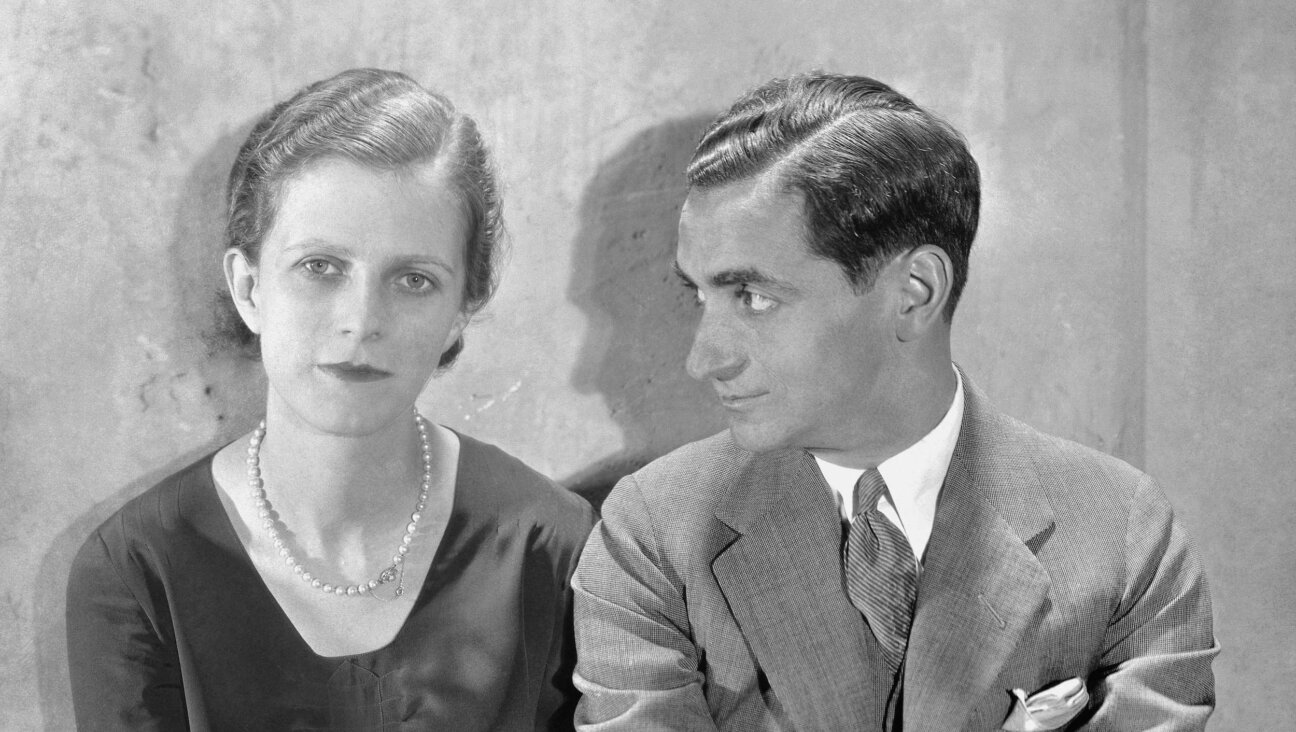

New York, 1947 – Cornerstone laying ceremony for Holocaust Memorial planned for Riverside Drive. Courtesy of YIVO

On a quiet stretch of Manhattan’s Riverside Park near 83rd Street, guarded by an iron fence, is a plaque that mostly goes unnoticed. But the inscription on the small flat stone laid in 1947 makes clear a bigger statement was intended.

“THIS IS THE SITE FOR THE AMERICAN MEMORIAL TO THE HEROES OF THE WARSAW GHETTO BATTLE, APRIL–MAY 1943, AND TO THE SIX MILLION JEWS OF EUROPE MARTYRED IN THE CAUSE OF HUMAN LIBERTY.”

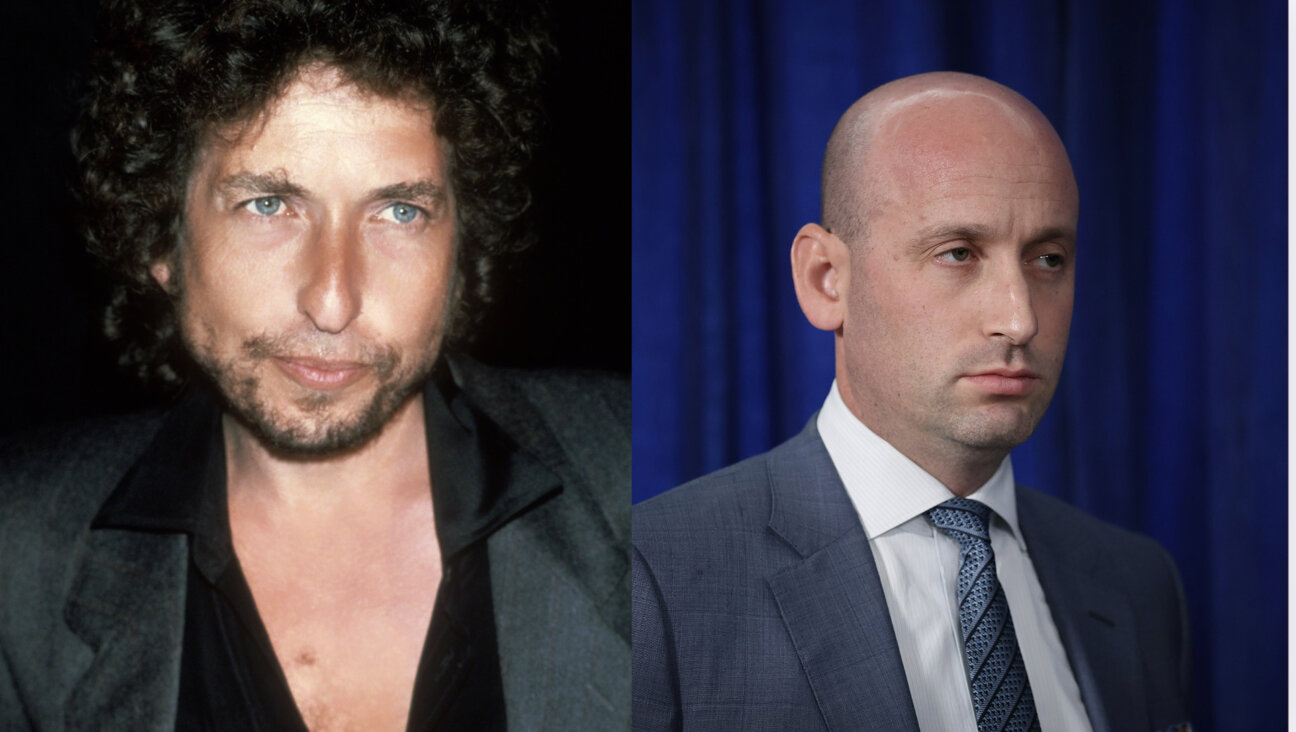

The granite plaque was placed as a temporary marker for the country’s first Holocaust monument. New York Mayor William O’Dwyer, speaking to a crowd of 15,000 in October 1947, promised a memorial in Riverside Park designed by the sculptor Jo Davidson. “It will be 50 feet high and 50 feet in diameter,” The New York Times reported.

However, Davidson’s sculpture of a muscular Jewish fighter defiantly towering above a rabbi with his arms outstretched over the fallen never came to be. Neither did the other seven design proposals that were made before the project was abandoned in the 1960s.

Every few years, a journalist writes about Manhattan’s never-built Holocaust monument. Generally, they reiterate a variation of a theory laid out in a 1993 Times article that the proposed monuments were all deemed “too ugly, too depressing or too distracting for drivers on the West Side Highway.”

But that explanation doesn’t feel satisfactory. Too depressing? Riverside Park’s main landmark is a tomb. Too ugly and distracting to drivers? Did the Times reporter ever visit Times Square? Even if these reasons were true in 1993, Holocaust memorials and museums have since then popped up at an astounding rate. Why hadn’t anything more substantial been made?

A ‘very pure’ commemoration

It’s not as if the plaque has been forgotten; it’s taken on great significance for some. Each April 19, the anniversary of the start of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, it is the site of a remembrance ceremony. At last year’s event, a mostly graying crowd of 120 sat in folding chairs or stood for two hours withholding applause between speeches and Yiddish songs of resistance.

After the ceremony, participants placed flowers on the plaque honoring the uprising and the 6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust. For decades, survivors, many of whom participated in the resistance, gave speeches in Yiddish. Now their children speak on their behalf in English. Still, they remember the Khurbn, not the Shoah or the Holocaust — using the term once favored by Yiddish speakers. The granite slab itself is called Der Shteyn (Yiddish for “the stone”).

In a phone interview, the feminist poet Irena Klepfisz compared the secular memorial to a Yarzheit, the annual Jewish ritual of

remembrance. For her, the ceremony is intertwined with the memory of her father, the Bundist militant hero Michel Klepfisz, who was killed in action on the second day of the uprising.

Klepfisz, white-haired and wearing a bubble gum pink jacket, spoke at last year’s event about the efforts the

Jewish Labor Bund, the Socialist party that held sway in prewar Europe, took to hide children. “I personally know of five child survivors who owe their lives to the devotion and determination not only of their parents but their parents’ comrades,” she said. Klepfisz was one of them, having been born in the ghetto in 1941.

“This is the only commemoration I go to every year,” the poet, who is on the organizing committee, told me. “I feel that what they do at Der Shteyn is very pure.” She called other events “commercialized.” In 2006, Arthur Krystal wrote in The American Scholar that he avoided Holocaust movies, documentaries, museums, and memorials — making an exception only for Der Shteyn.

I asked Shane Baker, the executive director of the Congress for Jewish Culture, who oversees the ceremony, why a true memorial was never built. Baker, 54, would seem to be an unlikely head of the April 19 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Memorial Committee. He grew up Episcopalian in St. Louis and, through a passion for Yiddish theater, became a leading advocate for Yiddish culture.

“We view the simple stone marker and our annual gatherings as ‘the monument,’ preferring an act of living memory to any grand statues,” Baker wrote back, seemingly bothered by my question.

After I apologized, he responded in more detail. “We are touchy because every time a monument is mentioned, another white knight comes riding to the rescue unbidden,” he explained. “Who knows,“ he wrote sarcastically, “maybe someone will come along and force through a plan for … a giant man facing the sun, or 400-foot-high tablets of the law, or a giant megillah decorated with death and destruction as have been proposed.”

I was a bit surprised by his response, which left me to ponder why a group committed to the memory of the Holocaust was not interested in a Holocaust monument. What had the monument come to represent?

Shifting goals

Before The Diary of Anne Frank and Schindler’s List, the Warsaw Ghetto uprising was at the center of Holocaust memory. In her 2009 book on Holocaust remembrance in postwar America, We Remember with Reverence and Love, historian Hasia Diner noted that the uprising became “the prism through which American Jews performed the memory of the 6 million.”

Tying together the heroes of the ghetto uprising with the murder of the 6 million allowed Jews to remember European Jews not just as victims, but as fighters against Nazism alongside Americans and other allies. Further, by projecting the motivations of the ghetto fighters onto all Jews in the Holocaust, one could give meaning to the destruction. Hence the plaque remembers “THE SIX MILLION JEWS OF EUROPE MARTYRED IN THE CAUSE OF HUMAN LIBERTY.”

Today, no one would suggest that European Jewry was “martyred in the cause of Human Liberty.” It is understood that Jews were senselessly murdered simply for being born Jewish.

The author of the inscription is not known, but the project to build a monument in Riverside Park was initially spearheaded by Adolph Lerner, a journalist and Polish Jewish refugee. According to a 1948 report by Lerner in the YIVO archives, he rushed to place Der Shteyn on Oct. 19, 1947, to rally support ahead of the November U.N. vote on the partition of Palestine.

“In his press release, Lerner seemed to imply that because of the Holocaust, the world — that is the United Nations — had the responsibility to create a Zionist state,” Rochelle Saidel wrote in her 1996 book Never Too Late to Remember about the development of New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage, which she connects to these early efforts.

Lerner initially received the support of Mayor O’Dwyer and the powerful Park Commissioner Robert Moses, who approved of the Riverside Park location. But the city’s Art Commission rejected the initial sculpture. Subsequent designs also failed. Moses’ department thought one took up too much park space, and there was a fear that a 60-foot stone pylon topped by a bronze menorah would be too startling to drivers, as alluded to in the 1993 New York Times article.

Saidel blamed more fundamental issues. “The main reason for its failure,” she wrote, “was that the organized American Jewish community, along with the government, had not set an agenda for Holocaust memorialization.”

Politicians, she argued, needed to champion the cause, not just show up for photo ops. Similarly, Lerner lamented that American Jewish groups were “aloof” and did not come through with funding or support. Jewish organizations were focused on supporting the living by aiding survivors and the nascent state of Israel, not remembering the dead. Diner quotes Rabbi Israel Tabak. “History,” the rabbi said in 1953, “has already established that monument; it is nothing less than the state of Israel.”

Cold War American politics presented their own challenges. McCarthyism had a chilling effect on Jewish organizations. Moreover, postwar American society had yet to embrace diversity and ethnic differences. “No minority group in America had yet created a museum, erected a massive monument on public space, organized university courses, or held an annual and highly visible lachrymose commemoration open to all, which focused on the painful events in their pasts,” Diner wrote.

By 1951, the goal was no longer for an explicitly Jewish monument, but rather a sculpture of the Ten Commandments, a symbol of shared Judeo-Christian values. That proposal failed after the artist Erich Mendelsohn died in 1953.

While mainstream American Jewish organizations moved on, survivor groups, especially those connected to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Bund, continued to gather each year at Der Shteyn.

In the more politically open 1960s, two competing Jewish coalitions proposed different monuments by the sculptor Nathan Rapoport, famous for the uprising monument in Warsaw. Survivor groups presented a design of Torah scrolls with bas-reliefs of scenes from the Holocaust, while Jewish labor groups pushed for a statue of a man engulfed in flames, an homage to Artur Zygelbojm, a Bundist politician who died by suicide in London in 1943 protesting of the world’s indifference to the death camps.

Both proposals were unanimously rejected by the City’s Art Commission for being too “tragic” for a park. Of course, New York parks have many monuments that memorialize tragedies. Eleanor Platt, a member of the commission, explained the difference to The New York Times in 1965: “They’re generally patriotic and have to deal with this country holding its own. It’s American history.”

In turn, the city suggested placing a monument first in Times Square, then by Lincoln Center, and finally in Battery Park, but according to Saidel, the Jewish community focused their fundraising and attention on Israel after the 1967 and 1973 wars, imperiling the project. Rapoport’s sculpture Scroll of Fire was eventually installed in Israel and in 1985, a less tragic Rapoport sculpture was approved for Liberty State Park in New Jersey. Instead of depicting a muscular ghetto fighter, the 15-foot bronze statue depicts a strong American GI carrying a weakened Jewish concentration camp survivor. A Jewish tragedy was recast as a patriotic symbol.

Eight years later, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, first initiated in the 1970s, opened on the National Mall, folding the Holocaust into the national consciousness and serving as a counterpoint to the American ideals of freedom and democracy.

“You hear, in the elevator up, the voice of a GI who has liberated the camps,” said Avinoam Patt, professor of Judaic studies at the University of Connecticut and a former researcher at the D.C. museum. “It frames the encounter with the Holocaust from an American perspective.” Even in New York, with a large Jewish community, the Museum for Jewish Heritage is positioned to tell the Holocaust as an American story. “You walk out at the end, and there’s the Statue of Liberty,” Patt said.

Saidel found that survivors embraced this narrative shift. “Those who arrived in the United States as survivors or refugees appear to be especially proud of the way the Holocaust has been ’Americanized,’” she wrote. “Perhaps it gives them the sense that they, too, have now been completely Americanized.”

A similar change occurred with remembrance events. In the early 1970s, the prominent survivor group Warsaw Ghetto Resistance Organization (WAGRO) started to reach out beyond the survivor community. “To this end, its activities were conducted mainly in English, rather than in Yiddish or Polish,” David Slucki, an associate professor at Monash University in Australia, wrote in the American Jewish History journal in 2019. In his article about remembrance of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, Slucki noted that WAGRO moved their yearly commemoration event from April 19 to Yom HaShoah, the day of remembrance established by Israel. And while the group, according to Slucki, was “nominally apolitical,” they leaned toward Zionism, despite having been founded by Bundists.

In 1972, WAGRO began hosting their Yom HaShoah event in the massive Temple Emanuel on Fifth Avenue. The commemoration “quickly became the largest annual Holocaust memorial event in New York City,” Slucki wrote, “attracting dozens of Jewish organizations as co-sponsors; prominent city, state, and federal officials as keynote speakers; and international figures.”

Irena Klepfisz remembers these large events. “They were very commercialized. A lot of politicians showed up, who [it] seemed to me, pardon the language, didn’t give a fuck about it,” she told me by phone. Klepfisz, who has worked as an anti-occupation activist, was also put off by these rallies presenting “Israel as the answer to the Holocaust.” Eventually, she stopped attending.

“In the mid-’80s, I rediscovered Der Shteyn,” she recalled. The service was still mostly in Yiddish, no politicians were invited to the podium, and she recognized people from the survivor community she grew up in. “It felt like a real memorial,” she said.

Slucki grew up in a Bundist household in Melbourne. His grandfather was a survivor, and as a child, he attended similar events in Australia. Speaking at the Riverside Park ceremony in 2018, he said that April 19 was his father’s Yom Kippur. His article in American Jewish History begins and ends with Der Shteyn.

“It was around the Warsaw Ghetto that survivors developed a language, a set of rituals, and a calendar that would form the basis of the Holocaust memorial culture that is more familiar today,” he noted. He sees Der Shteyn as a symbol of the Warsaw Ghetto narrative receding from the Jewish consciousness. “While it promised to stand as the eternal symbol of Jewish heroism and resistance,” he wrote, “today it is neatly tucked away in a Jewish neighborhood in Manhattan, easy to miss, the site of an ever-shrinking commemoration organized by the children of Bundists and others nostalgic for a lost world.”

I thought of Slucki’s words as the Der Shteyn ceremony came to an end with the singing of the Bundist anthem in Yiddish. Old friends hugged goodbye. “Any Bundists who are left, you know, you will see them at the Der Shteyn,” the late Miriam Erlich, the granddaughter of the prewar Bundist leader Henryk Erlich, said in a 2019 interview with the Yiddish Book Center.

The ceremony appears frozen in time. “At Der Shteyn, people do not come to visit the past, they come because they remain part of the past,” Krystal wrote in 2006. The event is a tradition fossilized in the plain stone that I had dismissed. I now understood that any monument would disrupt the 75-year-old ritual.

Klepfisz pushed back on my insight, though. “They’re not like the meetings I attended as a child,” she wrote in an email. Those first gatherings of survivors were raw in emotion. Today, at Der Shteyn, she explained, “they emphasize resistance in all its forms (not just armed) and avoid all the sadism and horror that the early memorials had — and which I as a child had a hard time with.”

Holocaust remembrance at Der Shteyn wasn’t a relic of the past. It had progressed, just on a different trajectory from the mainstream Jewish American community.

Klepfisz agreed that a monument would alter the ceremony, but in a practical, not a spiritual way. “The process of having a statue would take a lot of time, and the investment — including financial — would produce ‘debts,’” she wrote me. “People would feel that they were ‘entitled’ to speak as a ‘reward.’ The very process of having a statue would inevitably change the nature of the gathering.”

But more than not wanting to pay the political price for a monument, they truly don’t want one. If a monument is judged by its ability to spur remembrance, then Der Shteyn accomplishes its task — more so than the grandest monuments and the loudest politicians.

“Der Shteyn does not derive its poignancy from its grandeur,” the son of Holocaust survivors and chair of the program Marcel Kshensky said. “Der Shteyn,” he proclaimed, “derives its meaning from us.”

On April 19, musicians, academics, survivors and their families will gather at 2 p.m. at Der Shteyn in the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Plaza in Riverside Park, New York City.