How Maurice Sendak’s Jewishness shaped ‘Where the Wild Things Are’

The children’s book author was raised by Jews from Poland. A show at the Skirball in LA explores those roots

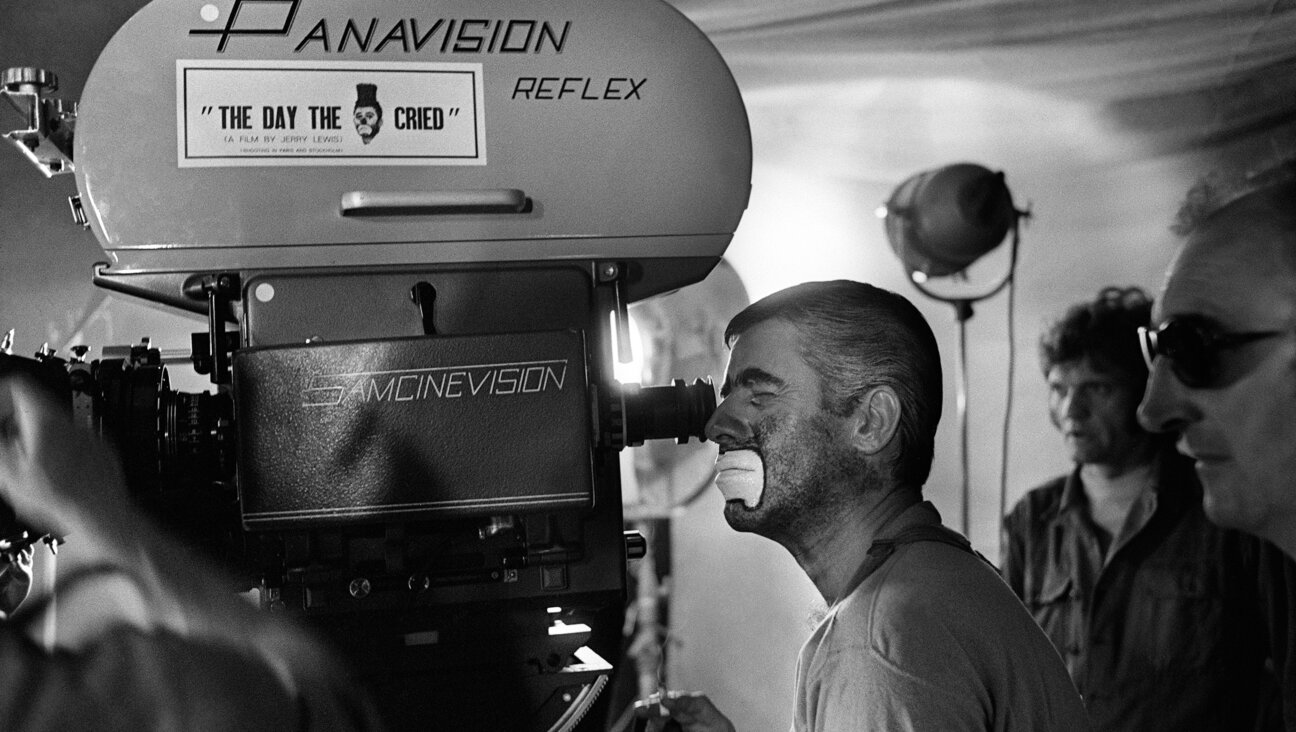

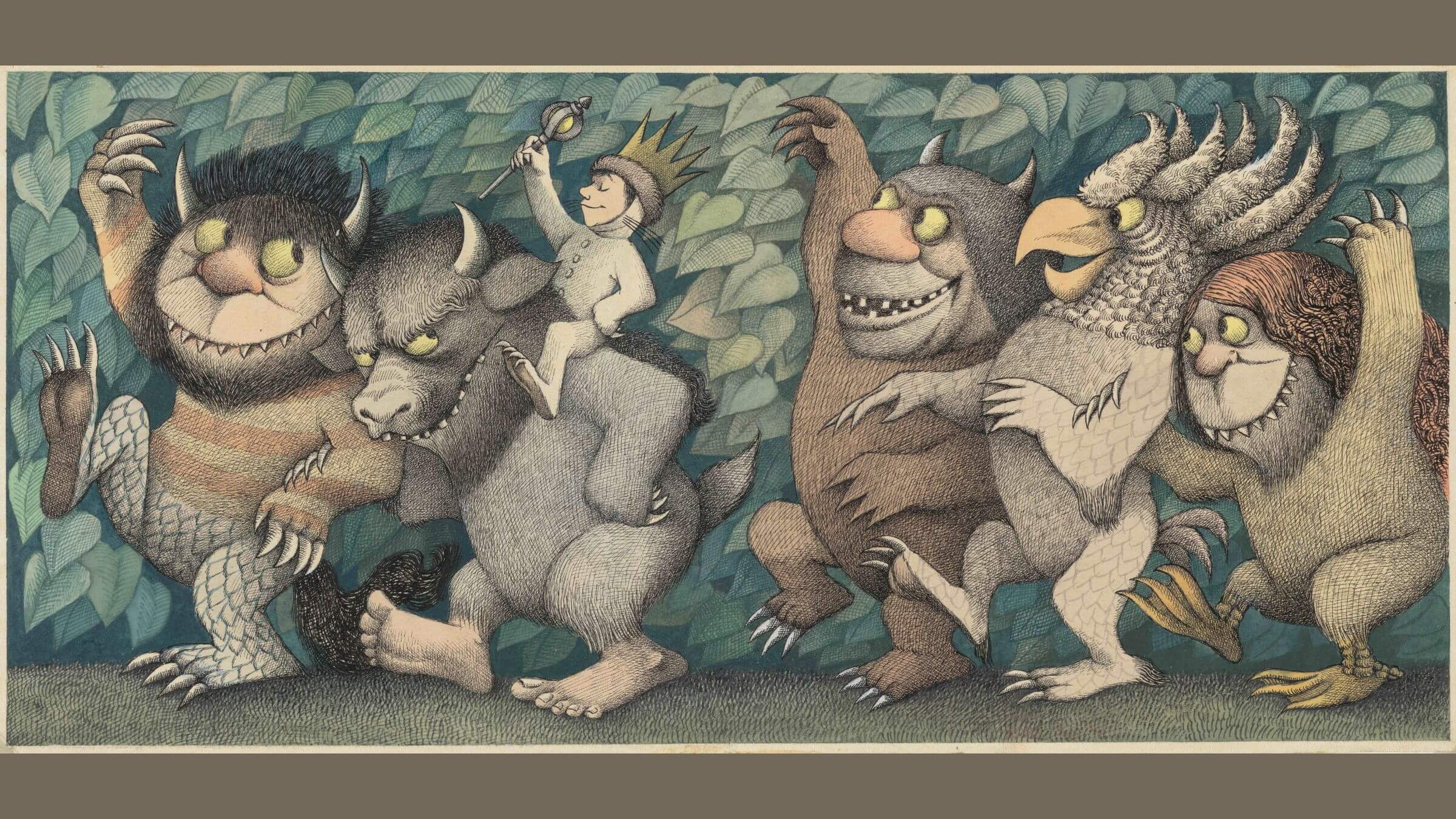

Illustration from Where the Wild Things Are. Courtesy of The Maurice Sendak Foundation.

A new exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles shows how Maurice Sendak’s Jewish roots shaped his work, including the title of his most famous book, Where the Wild Things Are.

“It’s what almost every Jewish mother or father says to their offspring,” Sendak is quoted as saying. “‘You’re acting like a vilde chaya. Stop it!’”

Vilde chaya is the Yiddish phrase for “wild child” — also loosely translated as “wild animal.” The monsters Sendak drew in Wild Things — lovably goofy despite their fangs, claws, horns and bulging eyes — channeled memories of relatives from his childhood in Brooklyn in a family of Jewish immigrants from Poland. These aunts and uncles would pinch his cheeks, and, like the creatures in the book, exclaim, “We’ll eat you up! We love you so!”

In fact, in posters he designed using Wild Things characters, he gave the monsters Jewish names like Moishe and Bernard.

Sendak scoffed at the notion that the book — about a boy named Max who tames monsters and becomes king of all wild things — was too frightening for children. “My experience suggests that the adults who are troubled by the scariness of (Max’s) fantasy forget that my hero is having the time of his life and that he controls the situation with breezy aplomb,” Sendak said.

Sendak, who died in 2012, was not religious, but he “felt a strong connection to his ethnicity and to what he called a Jewish sense of purposefulness,” according to wall text for the show, titled Wild Things Are Happening: The Art of Maurice Sendak. His father told stories from the Bible and of shtetl life, and Sendak grew up regarding books as “holy objects, to be caressed, rapturously sniffed, and devotedly provided for. I gave my life to them.”

The influence of the Holocaust

But there’s a darker aspect to Sendak’s childhood recollections. In an interview with The Guardian, he said that on the day of his bar mitzvah, in 1941, his father got word that their extended family in Europe had been wiped out by the Nazis.

Sendak was mindful that those same aunts and uncles who pinched his cheek could easily have perished. He “struggled to come to terms with the great question of how the same German culture that had produced his heroes Mozart, Schubert, (artist) Philipp Otto Runge and (writer) Heinrich von Kleist could do such terrible things,” according to wall text for the show. And he wove references to the Holocaust and the vulnerability of Jewish life into his work.

One drawing in the show depicts a Jewish tombstone illustrating Dear Mili, a Grimms’ fairy tale about a girl who encounters St. Joseph after her mother sends her into the woods to flee a war. The story is rooted in a Christian allegory, but “Sendak imbued the book with the experience of Jewish children during the Holocaust,” the exhibition says.

Wondering “how children could cope with such horrors” was also central to one of Sendak’s last works, his illustrations for Brundibar. The book, with text by playwright Tony Kushner, was inspired by a Czech opera of the same name performed 55 times by children in the Terezin concentration camp. The story is about siblings who sing for money to buy milk for their sick mother. They are chased away by an organ grinder, but friendly animals and other children ultimately help them. Kushner and Sendak also collaborated on a stage version of the story.

Other aspects of his career

In addition to displaying Sendak’s artwork, books and blown-up images of his fantastical creatures, the show explores other aspects of Sendak’s multifaceted career. He designed sets and objects for numerous stage productions, including a clock for an opera of The Nutcracker and an animatronic goose for a staging of Mozart’s The Goose of Cairo. He met his Harper & Row editor, Ursula Nordstrom, while working as a window-dresser for New York’s legendary F.A.O. Schwarz toy store. Three decades after Where the Wild Things Are was published, he even designed a balloon for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade as part of a promotion for a phone company.

Sometimes Sendak’s unwillingness to sugarcoat his work or bend to convention caused controversy. In the Night Kitchen was banned from many libraries because its hero, a little boy named Mickey, is naked. “The fact that people considered that outrageous — incredible,” Sendak said in an interview with NPR’s Terry Gross. “I mean you go to the Metropolitan Museum, you go to the Frick, you go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and there’s a Christ child with his penis. It’s accepted in fine art, but somehow in books for children, there’s a taboo.”

In the Night Kitchen, which depicts Mickey tumbling out of bed and into a kitchen where bakers nearly mix him into their batter, also celebrates Sendak’s love of the pop culture of his childhood. The protagonist is named for Mickey Mouse and the chefs’ faces resemble comic screen star Oliver Hardy.

‘You can’t protect kids’

To mark the publication of Sendak’s We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy — about homeless children living in cardboard boxes — Sendak collaborated on a comic strip for The New Yorker with his friend Art Spiegelman, author of the graphic novel Maus. The cartoon illustrates a conversation the two men had in which Spiegelman said, “When parents give Maus, my book about Auschwitz, to their little kids, I think it’s child abuse. I want to protect my kids.”

Sendak’s response summed up his philosophy as a storyteller. “You can’t protect kids,” he said. “They know everything.”

The Skirball Cultural Center in LA hosts the exhibition Wild Things Are Happening: The Art of Maurice Sendak through Sept. 1.