How Judaism mattered to Sigmund Freud — and why Freud mattered to Jews

Naomi Seidman writes about the relationship between Freud and the Yiddish and Hebrew translations of his work

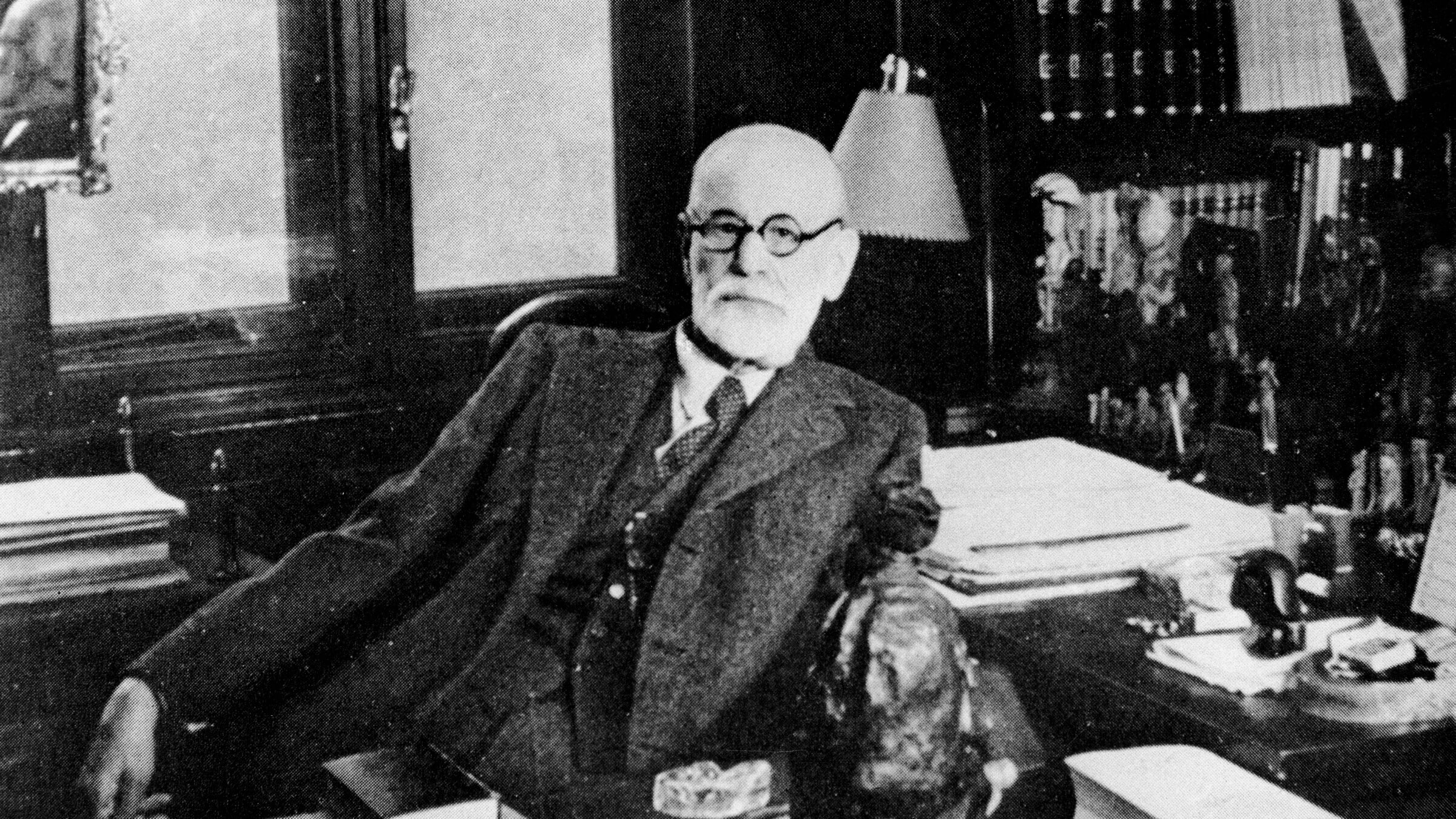

Sigmund Freud in his study, 1930s.

Freud mavens may have to reconsider their idol once again.

Early experts on the German Jewish founder of psychoanalysis, such as Ernest Jones and Ronald Clark, saw him as an assimilated Jew with little ethnic identity.

Others, like Marthe Robert and Marianne Krüll, looked to Freud’s Reform Jewish family to explain his attitudes about Yiddishkeit.

More recently, Emanuel Rice and Yosef Yerushalmi implied that Freud may have concealed the true extent of his closeness to Hebrew and Yiddish roots.

Now, Translating the Jewish Freud, by Naomi Seidman, offers a compelling, quasi-sociological view of how Freud’s Jewish admirers translated his works as a sign of prideful acceptance, which Freud himself valued.

Seidman argues that Freud wrote prefaces for the Yiddish and Hebrew editions of his works, which were accomplished not by trained psychoanalysts, but rather ardent devotees who aspired to draw Freud closer to the mishpocheh, especially as Fascist antisemitism overwhelmed 1930s Europe.

Seidman notes how at home, Freud would caress the resulting Yiddish and Hebrew volumes, which he claimed not to be able to read; he was sure to include them in the luggage when he fled his native Vienna for the UK in 1938, at the end of his life. To this day, these books sit on the shelves of the Freud Museum London.

She opines that the value of the translations is not in their skill, as they are “old-fashioned, dense, and often clunky.” Nevertheless, the early translators showed a good measure of chutzpah.

Freud’s Totem and Taboo, which contains essays on archaeology, anthropology, and the study of religion, was published in Hebrew in 1936. Its translator, Yehuda Dvir Dvossis, was determined to cite Jewish sources to bolster the author’s statements; he wrote to Freud that he planned to add several observations from the Biblical and Talmudic literature in footnotes not in the original text to “confirm and reaffirm [Freud’s] claims, and to occasionally shed new light on them.”

The linguist Max Weinreich, who translated Freud into Yiddish, was more punctilious about faithfully reproducing the writer’s ideas in the mame-loshn. But then Weinrich had honed his punctiliousness as a longtime contributor to the Yiddish Forverts, where he used the pen name Sore Brener, among other literary pseudonyms.

Weinreich, who almost managed to render into Yiddish Freud’s complete Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, was imbued with Freudian terminology. Nevertheless, he used a Jungian term to describe the YIVO Archives in New York as the “collective unconscious of American Jewry.” Carl Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious was opposed to the personal unconscious of Freudian psychoanalysis.

Author of the posthumously published landmark History of the Yiddish Language, Weinreich benefited from some brushes with psychoanalysis and spent part of 1933 studying with the child psychologist Charlotte Bühler (born Malachowski, of German Jewish origin) in Vienna, where he also befriended the Austrian Jewish psychoanalyst Siegfried Bernfeld.

For Dvossis and Weinreich alike, it was essential to underline to the reading public that the world-renowned ideas of Freud emerged from a Jewish kepele.

And to all appearances, Freud was genuinely delighted by these initiatives; he specified that no author royalty payments would be expected for these translations into Hebrew and Yiddish. In a letter to the publisher, used as an introduction to the Yiddish edition of his Introductory Lectures in Psychoanalysis, Freud wrote: “It has given me great joy to hear that the first volume of my Introductory Lectures is about to appear in Yiddish translation, and with great respect, I took the first pages in hand. A pity that I could not do more.”

According to the comparative literature specialist Zohar Weiman-Kelman, this note from Freud, although disclaiming any ability to read Yiddish, essentially proclaimed that Weinreich’s translation was a “kosher psychoanalytic text.”

No slouch at publicizing the kashrut of his work as translator, which he initially produced to celebrate the author’s seventieth birthday, Weinreich added in 1936 a series of five articles in the Yiddish Forverts to commemorate Freud’s 80th birthday, including insights on the “difficulties Freud faced in his career because he was Jewish.”

Even so, Forverts editors were chary about this apparent unrestrained boost for Freudiana, and so added a prudent caveat in the form of an editor’s note. It was admitted more or less that Freud was a big macher, but psychoanalysis itself remained a controversial treatment that the Forverts was not thereby endorsing:

“We on the editorial staff know full well that many people think psychoanalysis is a fraud, a way to make money. Nervous women go to a doctor, and pay them high fees to sit there and listen to them talk. The doctor recommends that they come every day for half a year, or even a full year, and that’s supposed to cure them. But we have such respect for Dr. Max Weinreich, an educated man of absolute integrity, that we have decided to allow him to introduce Freud to our readers.”

A groisen dank to those editors.

Weinreich’s presentation of Freud to Yiddish readers was seconded by other noteworthy examples of literary influence among Yiddishists, among them the Austrian poet Yehuda Leyb Teller (1912–1972) who also produced reportage in English signed Judd L. Teller. He recounted a visit to Freud’s office in Vienna circa 1938, describing Freud s as a “small man with a stone-gray face, with clever Jewish eyes and a vest buttoned up to his tie.”

According to Teller, Freud voiced disenchantment with what Vienna had become under threat of Nazi conquest: a “city whose senses are already completely dulled. Such a condition borders on madness.”

Soon after, Teller was inspired to create a series of Yiddish poems under the title Psychoanalysis, themselves a form of translation of the Freudian experience in a quintessentially Jewish format.

Amidst surreal imagery, Teller imagined Freudian nightmares traced back to childhood:

“Birds scream with mama’s voice./ Papa throws himself beneath the wheels./ A frog crawls out of the young boy’s hair./ Do you recall the dream of little Sigmund?”

Now an octogenarian, Teller’s Freud is described as awaiting the arrival of Nazi troops in Vienna:

“By day he peered out his window,/ Saw the saluting hands./ The Swastika. He smelled with his shrewd nose/ The old bad blood/ In young Aryan louts.”

Combining the themes of psychoanalysis and antisemitism, deemed by Seidman as a “return of both a repressed ancient hatred and a repressed Jewish consciousness,” Yiddish and Hebrew writers and translators placed Freud aptly in a context of historical tragedy.

In doing so, they offered a lasting reply to those still squabbling about how much Freud really identified with Judaism, resolving the issue with a resounding affirmation in Yiddish and Hebrew.