Why Hebrew is showing up in unexpected places — and why that matters

Three new books written in English — by Yael Van Der Wouden, Jessica Jacobs and Toby Lloyd — feature Hebrew in them

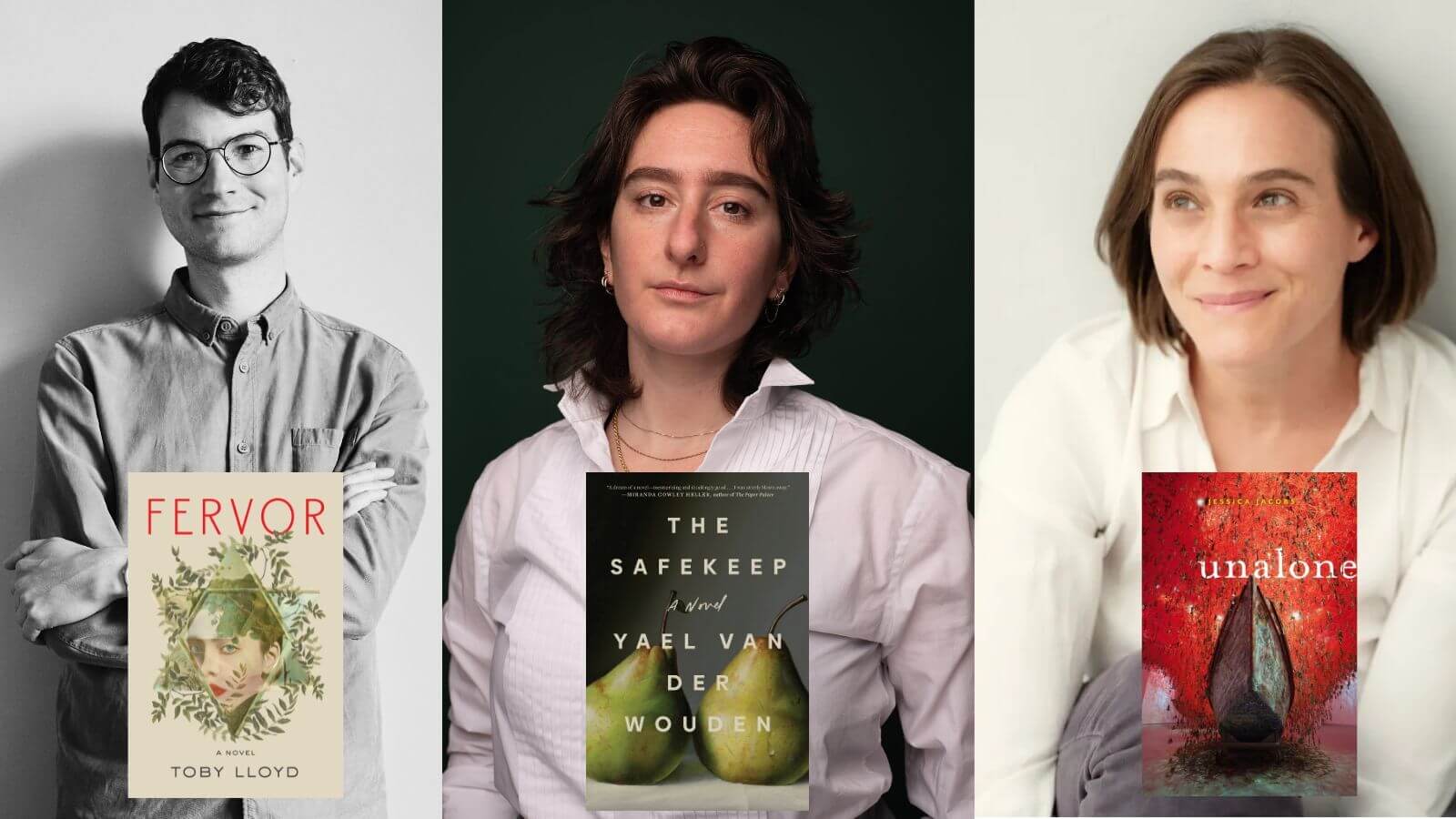

From Left: Toby Lloyd, Yael Van Der Wouden and Jessica Jacobs. Photo-illustration by Mira Fox

In the past few months, I have encountered three new English-language books that all have Hebrew in them. Though it’s become fairly common for English language books to contain snippets of Spanish — Promises of Gold by José Olivarez, for instance, or Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao —blending Hebrew and English, to my eye and ear, is significantly different. And there is also something special and notable about centering Hebrew right now.

Most English-language readers can make out a little bit of Spanish. In the United States, Spanish is widely studied and, according to the U.S. Census, more than 41 million Americans speak Spanish at home. The Spanish alphabet and the English alphabet are far closer than the Hebrew and English alphabets, which are wildly different. And Hebrew, of course, is written from right to left.

About 2.4% of America’s population is Jewish, numbering 7.5 million according to Pew, yet only a tiny fraction of American Jews speak Hebrew at home. Sure, day school students can handle a bit of Hebrew, and can read a few sentences of it in a novel or a poetry collection. “In the 2018–2019 school year, a total of 292,172 students were enrolled in Jewish elementary and secondary schools in the U.S.,” according to a report from The Avi Chai Foundation. Yet 65 % of these students are from Hasidic or “Yeshiva World” schools, and unlikely to be reading literary novels and poetry collections.

Meanwhile, Hebrew-school attendance, usually for the non-Orthodox, has decreased over 40 % between 2006 and 2019.

Yet two of the books I saw — Unalone, a poetry collection by Jessica Jacobs, who lives in Asheville, NC, and The Safekeep, a debut novel by Yael Van Der Wouden, who lives in the Netherlands — have actual Hebrew letters, the words spelled correctly, in the text. The third book, Fervor, an ambitious debut novel by the London-based Toby Lloyd, touches on many Jewish themes, from the memory of the Holocaust to the baal tshuva experience. It has a lot of Hebrew transliteration, though no actual Hebrew.

Hebrew in transliteration

The phrase Baruch Hashem — blessed is God — appears over and over in Fervor, sometimes in places where it seems awkward. I also found myself wondering if it should have been Boruch Hashem, in the Yiddish pronunciation, since a key character in the book is a grandfather from Yiddish-speaking Europe, recounting his memories. But transliteration aside, Fervor is a novel that sticks in my mind, because it is the rare book that addresses the question of belief; it also confronts Jewish history, and how individuals respond to it, and it also offers an up-close portrait of campus antisemitism that seems especially relevant right now.

The main character, Tovyah, a young man who grows up with a writer as a mother and a lawyer as a father, is an intriguing true intellectual; he really loves to learn, and has a voracious appetite for books. Though he grew up religious, he does not believe in anything. Naturally, his neighbor at Oxford is a young woman with a tenuous connection to Judaism, and a curiosity about it; the chapters she narrates are to my ear the strongest.

The book explores the question of what a writer can write about, and who a writer damages when she has free rein; it is a question most writers have come up against at some point. Fervor culminates in a horrifying event where a family member is destroyed by her own mother’s writing, or so the novel hints at, even as it allows for other possibilities — and other heartbreaks.

Having known individuals deeply damaged by a publication, this did not seem that far-fetched to me. Neither did some of the novel’s other dramatic moments — including a swastika and Star of David carved into Tovyah’s dorm door, or the memory of the Holocaust which haunts a grandfather on his deathbed. I won’t forget the grandfather’s haunting memory of walking a little boy into the gas chambers. As I read Fervor, I found myself thinking that the question of how we the grandchildren of survivors are affected by the Holocaust remains very much alive.

Hebrew — in Hebrew — in a novel in English

Yael Van Der Wouden’s The Safekeep, also confronts the long shadow of the Holocaust; like Fervor, it has many twists and turns within a gripping family narrative. But I was not expecting it to end with a quote from Isaiah 56:7. For my house will be called.

“She put the Bible away,” Van Der Wouden writes, “and went downstairs to finish the day: to sweep the rooms and wash this morning’s dishes and peel potatoes for dinner. Inside her the words repeated themselves, tumbled around: my house, my house, my house, echoed with her hands in a bucket of suds; devotion devotion devotion, a loop, drying a single knife. A single fork. A small teaspoon, its twisted neck; its drop of a head.”

Seven pages later, the book ends with Isaiah 56:7 in Hebrew, in bold, Hebrew letters. Not a translation, not a transliteration, but actual Hebrew.

Hebrew in the table of contents

In Jessica Jacobs’ Unalone, described as “poems in conversation with the Book of Genesis,” the Hebrew was less of a surprise: it was right there, in the beginning, in the table of contents. The book is arranged according to the parashot of the Book of Genesis, and the table of contents has the names of those parashot — like “Bereishit” — in actual Hebrew letters. I was delighted to see bits of Hebrew in the poems, as well, often when I least expected them.

So what does all of this mean? I think it says that several things are happening in the English-speaking world, all at once. Yes, there is increasing antisemitism and deepening concern in some circles about its spread in literary and cultural spaces; I say “some circles” because anti-Zionist Jews see this differently.

Fervor explores some of this tension, and does a good job depicting the isolation that Jewish students feel — even if they don’t agree with their parents’ views on Israel, or their parents’ takes on Jewish observance. It’s also true that the history of the Holocaust continues to haunt Jewish novelists in many countries, as can be seen in The Safekeep, from The Netherlands, and Fervor, from England. And while Hebrew itself is under attack, as the official language of Israel, which I believe is one reason why Yiddish and Ladino have been gaining popularity among younger language learners, there also seems to be a simultaneous rebellion — a desire to center Hebrew, to include it, to say, this language is a part of all these stories. There is a desire to insist on what Hebrew readers know: this language is eternally relevant.

This language is part of both belief and the questioning of it. It is there in England, in the Netherlands, in Asheville, NC. It is ancient and contemporary. And rather than hiding in the shadows, at this fraught moment, there it is, in both a table of contents and on the very last page of a novel. Take a moment to notice Hebrew making appearances in unexpected places. Long live this trend.