A bar mitzvah for a transgender man in the shul where he once had a bat mitzvah

Same bimah, same Torah portion — but this time, a ‘gender-affirming’ ceremony

Emet Marwell, wearing a prayer shawl in the colors of the transgender flag. Photo by Shana Sureck/www.shanasureck.com

Adult bar mitzvahs aren’t all that uncommon. But in July, Temple Shalom, a Reform synagogue in Chevy Chase, Maryland, hosted an adult bar mitzvah for Emet Marwell that was unique in many ways.

Marwell, 28, had stood on that very bimah in 2010, giving a d’var Torah — an explanatory talk — on the very same Torah portion from the Book of Numbers. Back then, though, Marwell was a teenage girl, having a bat mitzvah.

This time, instead of marking a transition out of childhood, the ceremony marked his gender transition. And this time, he’d thought a lot about what it means to be Jewish, trans and queer.

“I knew that my specific Jewish community, Temple Shalom, would be supportive,” Marwell said in a phone interview. “But I was nervous about Judaism more broadly, knowing that there are Jewish communities that might not be as supportive. So I really wanted to find out what Judaism itself says.”

Among the texts he turned to was Psalm 15, which asks of God, “Who may dwell in your sacred tent?”

The answer: Anyone “who speaks truth from their heart.” That passage helped Marwell choose a new first name: Emet, which means truth in Hebrew.

Marwell also found validation in pikuach nefesh, the Jewish law that prizes the preservation of life over all else. Transitioning, he said, “was what I needed to save my life.”

A rabbi’s allyship

The idea for a ritual honoring Marwell’s transition originated with Temple Shalom’s senior rabbi, Rachel Ackerman, who was one of Marwell’s Hebrew school teachers when he was a teenager. She recalled leading a retreat on gender and sexuality in Jewish tradition where “there was one student who knew more than I did.” That student was Marwell.

A few years later, as a student at Mount Holyoke College in Western Massachusetts, Marwell posted on Facebook that he was coming out as trans. Ackerman saw the post and messaged Marwell a hearty mazel tov and an invitation to celebrate in a Jewish way, whenever he was ready.

“I had always known she was an ally,” Marwell said. “But I wasn’t expecting her to reach out and offer something like that.”

At that point, though, Marwell’s Jewish practice took a backseat to other priorities: He was completing his studies at Holyoke and settling into his new identity. A few years later, after becoming active in a synagogue in Northampton, Massachusetts, he got back in touch with Ackerman and took her up on her offer.

Ackerman proposed a renaming ceremony and mikvah immersion, both of which Marwell ended up doing. But the bar mitzvah idea, she said, was “all Emet.” It was the first time Temple Shalom had hosted a “gender-affirming” bar mitzvah, and the guest list included some of the Hebrew school teachers and classmates who’d witnessed his bat mitzvah 14 years earlier.

It was a perfect way to “reclaim that space,” as Ackerman put it, and show Marwell that “Judaism values you, and sees you in the wholeness of who you are.”

Adopted from China as a baby

Marwell was adopted as a baby from China and raised in the Washington, D.C., area by a single mom. His mother Emily’s interest in Judaism had always been more cultural than religious. But when he asked, in fifth grade, why he wasn’t prepping like other kids for a bar or bat mitzvah, she enrolled him in religious school and joined Temple Shalom. She was there for both his bat and bar mitzvah, standing beside him and cheering him on.

But Marwell’s experiences as an Asian Jew, starting when he was young, have not always been easy. At one point, a cantor wanted to schedule Marwell’s bat mitzvah on the same day as another Asian American child whom the cantor kept referring to as “Oriental.” The cantor’s use of that term and insistence on a double ceremony when Marwell and his mother didn’t want one felt “racially motivated,” Marwell recalled. His mother went “storming out” of the meeting with the cantor, and Marwell ultimately did not share his ceremony with the other child.

Another time, he was attending services alone and a woman kept asking him who he was with. “She was implying that I couldn’t be Jewish, that someone brought me in as a guest,” Marwell said — even though he ended up showing her the right page in the prayer book when she lost her place.

At least in progressive Jewish circles, “the part where I’m trans and queer is so easy,” he said. “People get that. They understand that. But they can’t understand that I’m a Jew of color.”

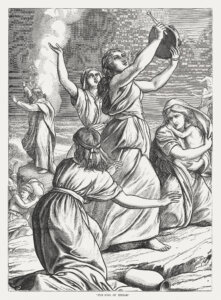

Finding inspiration in Miriam

Marwell’s speech about his Torah portion focused on a single sentence from the passage: “Miriam died there and was buried there.”

When he’d read that sentence as a teenager, he said in his d’var Torah, “I hadn’t yet grasped a full understanding of my own gender, and I also failed to understand the importance of Miriam’s death and her legacy.”

Reading it now, Marwell was outraged on Miriam’s behalf; he felt she deserved more recognition than those few words. After all, she had cared for her infant brother Moses, helped lead the Israelites’ flight from Egypt and sustained them with her life-giving well of water.

Miriam “broke free of the expectations of women, shattered the binary of traditional gender roles, and melded the feminine and masculine as a woman in a leadership position typically only held by men,” Marwell said.

And now that Marwell had found his own “identity as a trans man, and thought deeply about gender roles in the process,” he said he too had “broken free of traditional gender roles.”

He ended his talk with a call to action, asking congregants to make phone calls and write letters opposing anti-trans legislation introduced this year in 38 states.To follow Miriam’s guidance, he added, is to “rise above gendered expectations” and “choose to sustain the lives of all trans people.”

‘A seeker, speaker and educator’

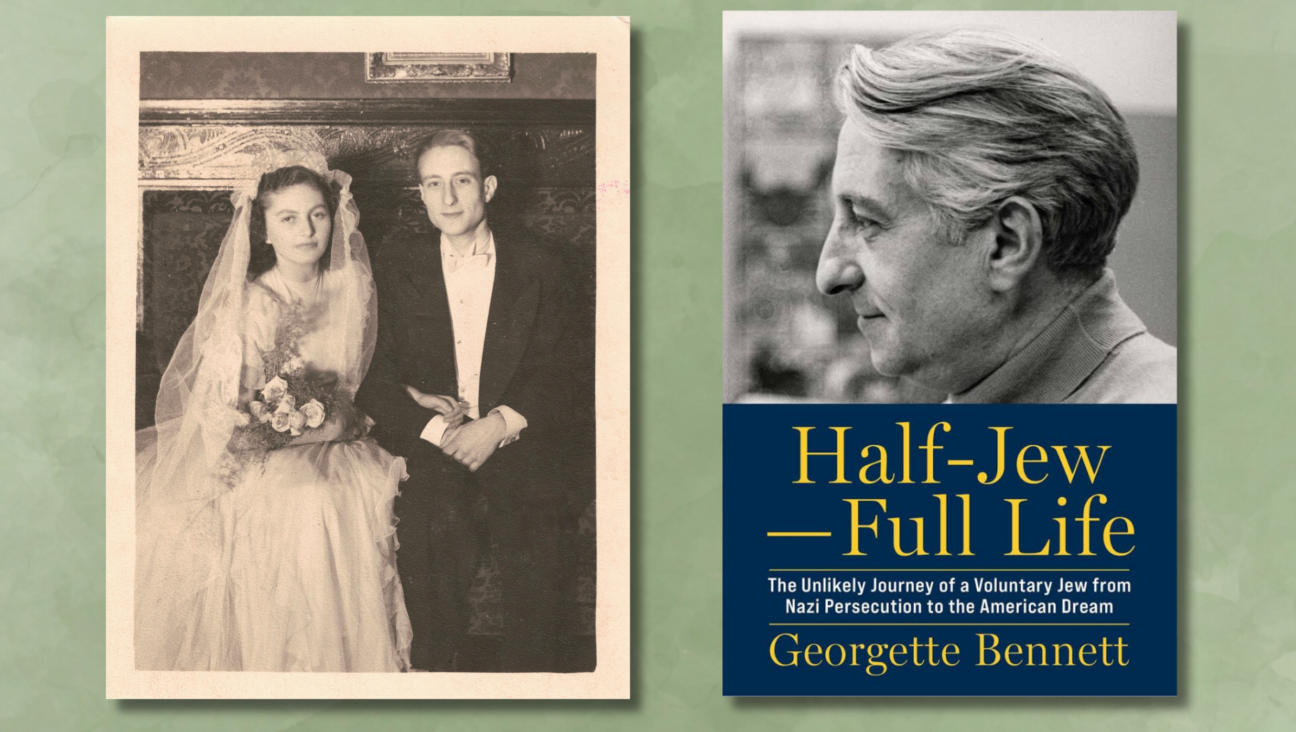

Among those attending his bar mitzvah was a photographer, Shana Sureck, who’d met Marwell in a class at their Northampton shul. When she learned his story “of being adopted from China as a girl by a single mother in D.C., transitioning in college, and deepening his faith throughout this journey,” she wrote in a Facebook post with photos of the event, “I knew I had to go and document this important ritual.”

A member of their class in Northampton made Marwell a tallis in the colors of the trans flag, she noted, and another classmate knitted him a matching yarmulke. She ended the post by invoking the Hebrew meaning of Marwell’s new name: “You are indeed a seeker of truth, a speaker of truth, and an educator about truth, just as your name suggests. You have deepened my understanding of what it means to be fully human.”

Indeed, Marwell is already carrying out the work as a seeker, speaker and educator that so inspired Sureck. He’s teaching a class at their Northampton shul — and planning on applying to rabbinical school.