In place of a proud emblem of Jewish immigration in NYC, million-dollar condos and a private garden

Gentrification comes for the Bialystoker Center and Home for the Aged

Facade of the 1931 Bialystoker Home for the Aged on New York’s Lower East Side. Courtesy of courtesy of Elissa J. Sampson

When the Bialystoker Center and Home for the Aged opened on Manhattan’s Lower East Side on June 21, 1931, more than 25,000 Eastern European Jews came out to celebrate. The distinctive Art Deco tower that rose from the tenements of East Broadway was a glimmer of hope during the depths of the Great Depression. The dedication 25 years after a pogrom that claimed the lives of more than 80 Jews in the Polish city of Bialystok highlighted how far the immigrant community had come.

This October, the building, which closed its doors in 2011 and relocated its last senior residents, will reopen. The tower’s landmarked two-toned tan facade designed by the architect Harry Hurwit has been restored. As has the faux-Hebrew inscription of “Bialystoker” surrounded by roundels of the 12 tribes of Israel above the entrance. Inside, the stained glass windows in what was the retirement home’s synagogue glow anew.

But this time around, there will be no parades, no congratulatory telegrams from the governor’s mansion, and no ceremonial golden mezuzah installation.

The building that for decades housed Jewish and other seniors and served as a center for the Bialystok Jewish diaspora has been gutted, refilled with loft-like apartments, a pool, gym and communal spaces. It’s connected to a private park and a new 28-story tower in a 70 apartment project called 222 LES Tower + Lofts.

The community has resisted each step of the development since the nursing home closed. Organizers won landmark preservation for the building and blocked an attempt to build a second tall tower, but gentrification pressed on. Along with this publication’s former headquarters, the Forward Building which became condos in 2006, and the nearby Jarmoulowsky Bank Building which opened in 2022 as a boutique hotel, it is another example of a working-class Jewish Lower East Side institution that served the public turning luxurious and exclusive.

During the Depression, the stately brick Bialystoker Home stood as proof to Jewish immigrants that their mutual aid societies (landsmansshaftn) remained strong. At the dedication ceremony, local congressman Samuel Dickstein declared that the edifice proved that the Jewish community has always “taken care of their own people, without calling upon the government to find a place for the orphans and the aged.”

Now, the tower stirs up locals’ anxieties of rising rents and displacement. Once a symbol of collective achievement, it symbolizes inequality: another one of the many new doormanned citadels of wealth. Out-of-reach apartments for out-of-touch tenants.

“They took out all the old people from here,” said Jess, a 49-year-old resident of the LaGuardia Houses, a nearby public housing project, who says she knows people with elderly relatives who were relocated from the nursing home. “They fix things up and they try to force the people out who have been here their whole lives out.”

‘An amazing statement about immigration and assimilation’

95 years before anyone considered opening a yoga studio or coworking space on East Broadway, and a month before the stock market crashed, on Sept. 22, 1929, the Bialystoker Center cornerstones were laid. Two prominent families, the Lutenbergs and the Marcuses, both wished to make large donations for the Bialystoker Center. Not wanting to turn down a donation or offend anybody, David Sohn, the head of the Bialystoker Relief Committee managed to have two cornerstones simultaneously placed.

Rebecca Kobrin, Columbia professor of history and the author of the book Jewish Bialystok and its Diaspora, credits Sohn, who died in the home for the aged in 1968, not just for the building, but for the outsize imprint that the Jewish emigres of Poland’s 10th largest city left on the Lower East Side.

Near the Bialystoker Center and Home for the Aged is the Bialystoker synagogue on Bialystoker Place, a short walk to Kossar’s Bagels and Bialys (long called Kossar’s Bialystoker Kuchen Bakery) famous for producing the city’s famous doughy bread, the Bialystoker kuchen, known simply as bialys and often described as the bagel’s baked hole-free cousin. It’s perhaps Jewish Bialystok’s most enduring legacy after Esperanto, which was invented by the ophthalmologist Leyzer Zamengov who was born in the city in 1859 when it was part of the Russian Empire.

Sohn arrived in New York from Bialystok in 1911 at the age of 21. In 1919, then a house painter, he began fundraising to rebuild the Polish city after World War I. Unlike most Eastern European cities, Bialystok was majority Jewish which gave its diaspora a strong and cohesive identity. Between 1919 and 1932, according to Kobrin, Bialystoker Jews in the United States, Australia and Argentina sent back $9 million (the equivalent of over $150 million today).

“After they coordinated to rebuild Bialystok,” said Kobrin, “they decided that they were going to use some of their money and their great acumen at fundraising to build something for the Lower East Side that could serve their community.”

The project didn’t just help aging Bialystoker emigres, it made a statement. A few months after the Empire State Building opened on Fifth Avenue, the Bialystokers’ Moorish Art Deco building, with its top hat-wearing doorman announced that the Jazz Age had arrived on the East Side.

Sohn and his cohorts had gone from Ellis Island refugees to Jewish-American leaders. Their transition is mirrored in the “Bialystoker” sign preserved above the entrance written in English but in letters that look like Hebrew.

“What an amazing statement about immigration and assimilation, as Yiddish becomes English and immigrants become Americans,” architectural historian Andrew Scott Dolkart wrote in 2012 to the Landmark Preservation Commission calling it “one of my favorite details in New York and an amazingly pointed symbol of our history.”

But Bialystok arrived on the Lower East Side just as the Jews were leaving. Sohn himself had already moved to the greener pastures of the Bronx, part of a mass exodus of Jews that only accelerated during the Depression.

In the 1950 census, most of the 100 or so residents of the nursing home list Poland as their birthplace. They’re mainly retired garment district cutters and stitchers whose American-born children and grandchildren are professionals spread across the New York area.

In 1992 when the food writer Mimi Sheraton visited the building to research her culinary history book The Bialy Eaters, the center was still publishing its Yiddish and English newsletter the Bialystoker Shtime which persisted for another decade. But at the time, of the home’s 95 residents, only two were born in Bialystok. Others were Jewish or, increasingly, Latin American, a reflection of a changing neighborhood.

Soon after, the hardscrabble neighborhood began attracting artists, followed by designers, restaurateurs, gallery owners, and then inevitably real estate developers. By the 2000s, the senior home which itself had reached old age was losing money each month, while property values continually climbed.

A garden for the wealthy

In the musical, The Producers the fictional character Max Bialystock realized he could turn a profit by sinking a Broadway show. Some accuse real world Bialystoker board members of also profiting off of failure.

When the home closed in 2011, the nursing home recreation director suggested to a Forward reporter that the home closed as a result of willful neglect. A judge later struck down the board chair Ira Meister’s $1.5 million purchase of a three-story office building owned by the Center and adjacent to the Bialystoker home as self dealing.

The Bialystoker Center and Home for the Aged board members further raised the ire of the community when they initially resisted efforts to protect the facade of the building. The board argued that the Bialystoker Home, adjacent office building, and garden needed to be sold to developers to cover the nursing homes’ debts and the cost of relocating the residents. In 2016, the properties were acquired for $47.5 million by the developers RoundSquare Development (then called Ascend Group).

RoundSquare subsequently attempted to acquire the air rights of the neighboring Seward Park Cooperative, a four building complex built by labor unions in the 1950s. With the air rights, they could build modern towers on each side of the Bialystoker home. The $54 million purchase offer sharply divided the coop’s residents.

Mendy Erez, a 73- year-old retired electronics seller who was born on the Lower East Side and has lived in the Seward Park Coop for over 40 years, supported the sale. Erez, who was on the co-op board at the time of the vote, told me it was the co-op’s only opportunity to sell the valuable air rights and benefit from the neighborhood’s building boom. The money, he said, was needed for repairs and financing.

Others argued the two new glass towers would cast a shadow on the coops and were antithetical to their values. “With only luxury condos and no affordable units, the Ascend project undermines the diversity of our surrounding community,” one resident wrote in an op-ed on the Lower East Side news site the Lo-down at the time.

The offer did not pass a shareholder vote and RoundSquare was forced to confine itself to converting the landmarked building to “loft apartments” and to a single new tower on the east side of the Bialystoker Home. The other side at the corner of Clinton Street, instead of becoming a second tower, is a 6,700 square foot private garden.

The new modern tower blocks Erez’s view, but he’s more bothered by the private garden. “It should be also for the residents of our building,” he said. The lot, he claimed, was donated by the co-op to the nursing home 40 years ago to give the seniors outdoor space. Neighbors like him were welcome inside what was called the Doris Cohen Memorial Park. “We didn’t donate it so that somebody should make a profit and keep us out of there,” he said.

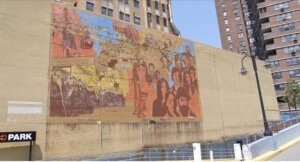

Adding to local resentment is the fact that, in 2016, RoundSquare whitewashed the Jewish Heritage mural painted in 1973 on the office building abutting the Bialystoker Center and Home. The mural depicted the Jewish Lower East Side and Jewish religious life and tragedies like the Holocaust, and the 1972 massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. Roundsquare founder and president Robert Kaliner at the time promised the non-profit public art and education organization that originally painted the 1973 wall, CITYarts, that they would sponsor a new mural that would represent the neighborhood’s diverse communities.

RoundSquare did not respond to questions, but according to an email from CITYarts Executive Director Tsipi Ben-Haim, the developers never followed through on an initial discussion of an art project for their new building. No artwork has come to replace the popular mural that featured the motto: “Our Strength Is Our Heritage, Our Heritage Is Our Life”

‘Where are the people?’

The sleek marketing of 222 East Broadway focuses instead on the future. “New and Blossoming on the Lower East Side” reads the top of their website, which promotes the neighborhood’s “new emerging art and dining scene” and the building’s “luxe amenities.”

On a tour of a $2 million two bedroom, I was pitched on the in-unit washing machines and the downstairs gym and pool. There are also co-working spaces, a private park and a play space for children. Seemingly, one doesn’t ever have to leave the building. Why shop for groceries when the building has cold storage for perishable deliveries?

All this adds to a feeling among long-term residents that their new wealthy neighbors may live in the community but are not part of it — a departure for an East Side that long lived cheek to jowl and still crowds its parks, libraries and markets. “They put up about 14 buildings. The supermarkets don’t benefit. The synagogues didn’t benefit,” said Erez who grew up in a tenement. “Where are the people?”

Erez might not be able to access the buildings’ amenities and they may have taken away his sweeping view of the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridge, but the facade of the Bialystoker Home remains on view for everyone, a testament to the neighborhood’s communal past. The historian Kobrin told me that Sohn, the fundraiser and longtime executive director of the Bialystoker Center, understood that “the built environment makes an imprint” and that he built the center and nursing home to ensure Bialystok left its legacy on East Broadway.

On a recent afternoon, the Bialystoker Home entrance of the building was being worked on, perhaps for the first time in a decade. I was told the entrance would be fully restored to its former glory. Next to the door was a small plaque placed in 1969 reading “This Tree Donated in Memory of David Sohn.” Underneath it, the ground was still barren.