For Europe’s Jews, owning grand homes symbolized not just wealth, but equality

In many places, Jews couldn’t own property until the 19th century. Exercising that right gave them social and political status, a new book explains

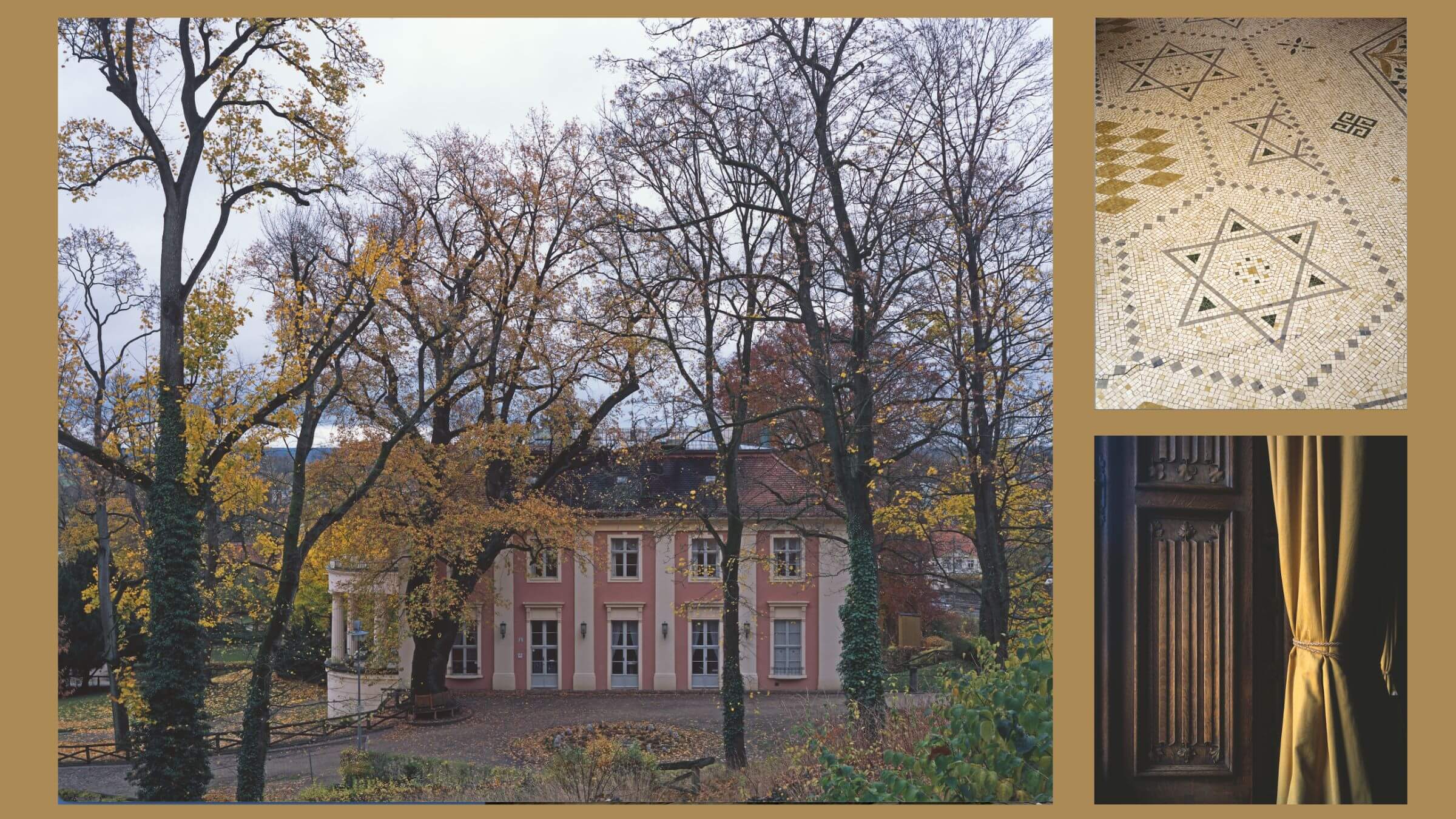

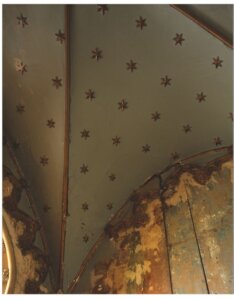

Left: The Schloss Freienwalde house, in Bad Freienwalde, Germany, once owned by Walther Rathenau, a Jewish foreign minister in the Weimar Republic. Top right: Stars of David in a tiled floor at Villa Kérylos on the French Riviera, built for Theodore Reinach, who founded the first Reform synagogue in France. Bottom right: Drapery at Strawberry Hill House, Twickenham, England, once owned by Lady Frances Waldegrave, the daughter of a Jewish opera singer. Courtesy of Profile Books. All photos by Hélène Binet/Jewish Country Houses

Abigail Green is nervous about Jewish Country Houses, the book she co-edited. And her concern is understandable: At first glance, the book could be perceived as an ode to wealthy Jews in a bygone European era, along with their art and architecture, fancy furnishings and manicured landscapes.

But take a closer look. This book shows how, for centuries, Jews were denied the right to own land and live where they pleased. When those rights were finally granted — in 1831 in Britain; with the revolution in France, and elsewhere, later — Jews who could afford it manifested their newfound privileges by buying and building lavish homes across Europe.

Yet these houses were not merely symbols of material success. They also cemented the social and political status of Jews who had until then been excluded from the upper classes, even when they were wealthy enough to belong there.

Of course, all that changed when the Nazis took power and World War II began. Which is why Jewish Country Houses is also “a book about the fate of Jews in Europe,” Green said in a phone interview from London.

‘Subversive houses’

The book was a collaborative project, co-edited by Green and Juliet Carey, with chapters and other material contributed by researchers and experts across Europe. It was published by the National Trust and Profile Books in the United Kingdom and Brandeis University Press in the U.S.

The moody, detailed photography by Hélène Binet – showcasing Stars of David in a ceiling or floor, or an architectural style reflecting an owner’s particular tastes – was particularly important, Green said: “Photos of country houses where it’s always a sunny day with jolly flowers and a green lawn are not appropriate for these stories.”

Green’s mother was a Sebag-Montefiore, one of Europe’s best-known Jewish families along with the Rothschilds, Salomons, Warburgs and Sassoons. “So it wasn’t news to me that Jews lived in the country and went hunting,” Green said. “But these houses tell a different story. They are basically subversive houses, because they are part and parcel of a Christian feudal system that ran through rural Europe and rural society. For Jews to own these houses, when they were regarded as so alien that they couldn’t own land, is a subversive thing. And the idea of a Jewish aristocracy is a very subversive thing.”

On the other hand, Green said, Jewish country houses have also been criticized as “sites of assimilation. The families are viewed as sellouts who became distanced from Jewish society.”

That is not “a fair assessment,” she said. Not only were the owners’ social circles and neighbors acutely aware of their Jewishness, but often these wealthy Jews were major philanthropists, supporting Jewish charities in their own countries as well as funds for Jews in Palestine and elsewhere.

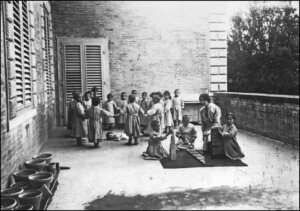

Owning property was also a way for Jews to access political power. As landowners, they could acquire titles as members of the nobility; they could host parties and events for other elites, including royalty, and they were expected to take responsibility for the community whose work they relied on to run their estates. They built schools, modernized agriculture and sometimes even supported churches. Such acts of noblesse oblige paved the way for Jews to run for office and represent those communities in government. In Ireland, for example, Lady Desart, who built homes for local woodworkers in a model village near her country home outside Kilkenny, became the first Jew to serve as a senator in the Irish Free State.

The Nazi era

In the Nazi era, as Jews fled, hid or faced deportation and mass murder, their properties were seized and sometimes destroyed, either intentionally or as the result of warfare. Even homes that survived the war were often emptied of all traces of their owners, repurposed by Communist regimes, or simply deemed unworthy of preservation because their aesthetics did not match prevailing tastes.

Among the many wartime tragedies is the story of renowned painter Max Liebermann, whose success allowed him to build a retreat and villa in Wannsee, a Berlin suburb. Liebermann was kicked out of the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1933 and died two years later. His widow was forced to sell the villa to the Third Reich. When told she’d be deported to a concentration camp, she took a fatal dose of sleeping pills. Today, the Liebermann estate is a museum, but the family’s possessions are gone.

“It’s very beautiful and the volunteers are very keen on the garden and that kind of thing, but it belies the terrible experience of the Liebermanns,” said Green. “It’s empty; there’s a few paintings but no furniture, nothing in it. And that’s a common fate of these houses.”

In a few cases, however, Jews recovered their estates and even used them to help survivors. For example, the Warburgs used their German villa to house Jewish children liberated from concentration camps.

Another Jewish country house in England, Trent Park, owned by the Sassoon family, was the site of lavish parties in the 1920s and ‘30s attended by Winston Churchill, as well as a love nest for the future King Edward VII and his American mistress Wallis Simpson. But during the war, Trent Park became a genteel prison for 100 German officers who were encouraged to stroll in the garden and play billiards. They had no idea their conversations about Nazi weapons technology and concentration camps were being monitored by German-fluent Jewish refugees via tiny hidden microphones. Today Trent Park is open to the public, and a museum related to the war effort is being planned.

A positive reception

In Britain, unlike in the U.S., “most people don’t meet many Jews,” Green said. “They just don’t know much about any of this.” So she and her colleagues have been pleased by positive reactions to a traveling exhibition related to the book, along with presentations and training sessions for National Trust staff and volunteers about the homes’ Jewish history. Even an exhibition about the houses in a National Trust garden was “completely unproblematic” despite fears of vandalism after the Oct. 7 attacks.

Green hopes the book will also get a positive reception — and that it will help people see the properties as more than repositories of material wealth. These houses, she said, symbolize “the dream of belonging” held by European Jews, “and that moment when it seems possible. But the houses also represent something that is irreparably gone, destroyed by the Holocaust.”

Now they have a new life, she said, as “sites of teaching about antisemitism.”