Nazis are praising Hitler’s art prowess. But was he really any good?

The not-very-surprising answer is: no. But why?

The signature of Adolf Hitler at the painting “Prague in the Fog.” Courtesy of Getty Images

Now that social media is barely moderated, speech is freely flowing, full of slurs and praise for various dictators. For example, as one viral tweet posited, how Adolf Hitler’s paintings were actually way better than more lauded Jewish artists such as, in this example, Mark Rothko.

The poster described Rothko’s famous 1951 painting “Number 6 (Violet, Green and Red)” as a “blob” and “three unsymmetrical rectangles.” In contrast, he highlighted Hitler’s painting, “Neuschwanstein Castle,” which he said was “literally too good” for the “decaying system” to appreciate.

Before he wrote Mein Kampf, Hitler worked for years as a street painter, producing, conservatively, hundreds of works, though he found little commercial success. He applied twice to the prestigious Academy of Fine Art in Vienna, but was rejected both times.

For Hitler’s adherents today, this is an unimaginable affront — though, of course, if Hitler had made it as a painter, he probably wouldn’t have done all the fascist things they now love him for.

Appreciation for Hitler’s paintings is nothing new among neo-Nazis; adulation of the Nazi leader, as in any sort of ideological devotion, encompasses everything he touched. (His art also seems to have started generating more attention recently thanks to a trend of referring to Hitler as “the Austrian painter” as a way of evading moderators; not a problem anymore!)

To be entirely fair to the neo-Nazis (not that we should be, but stay with me), Hitler’s artwork is not exactly bad, especially to an untrained eye. I certainly could not paint a castle as well as he did, though that isn’t really saying much. He even got an agent — ironically, a Jewish man named Samuel Morgenstern — and managed to sell a few of his pieces when he was young and trying to make a living as an artist in Vienna.

But to many people, the capability to create good art implies some deep understanding — of the world, of the human condition, of beauty. And imagining that Hitler could tap into the depth of the human experience is uncomfortable. So was his art any good? Let’s get into it.

The missing vanishing point

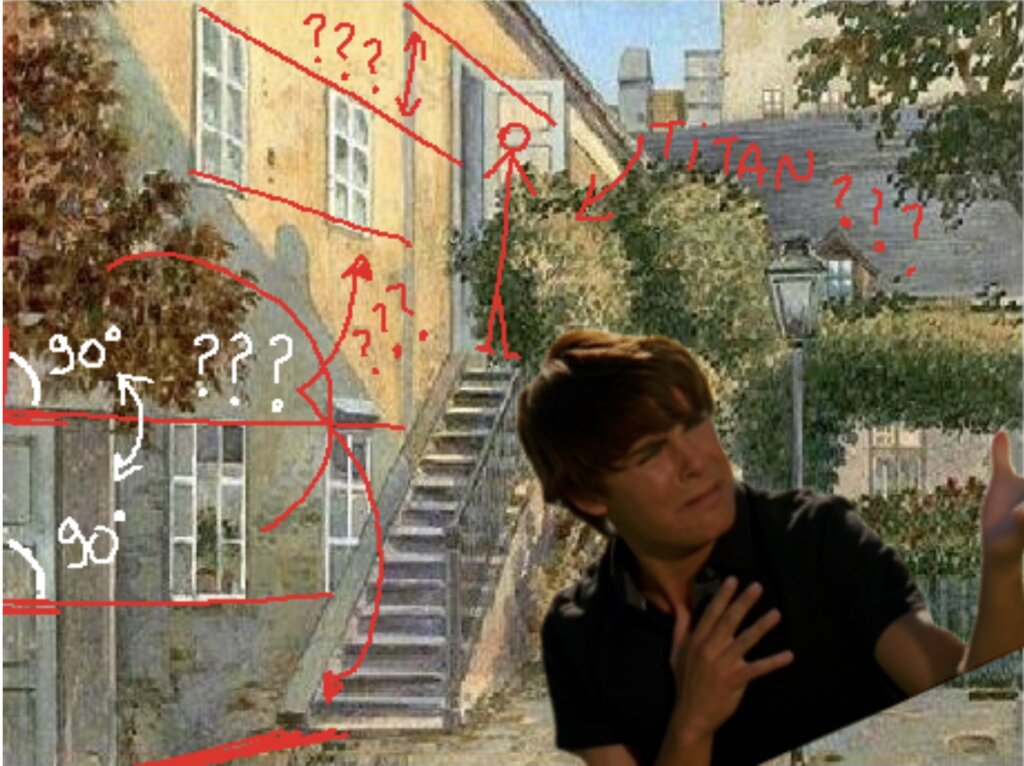

user: “mother-fucking-fate-nanodayo” that regularly makes the rounds online. Courtesy of Tumblr

One of the most discussed — examples of Hitler’s flaws as a painter is a watercolor depicting a courtyard. In it, stairs lead up to a windowed building, a lamppost out front and a few trees scattered around.

At first glance, it appears to be an unremarkable but competent piece. But, as numerous Reddit threads break down, the perspective is off. The light source seems to be coming from multiple different places. One window appears to be facing the viewer directly despite its placement on an angled wall. Another window is cut off by the stairs. A second-story door is far larger than it should be. In short, the vanishing point — a basic technique of conveying perspective in painting — is all wrong.

Skewed vanishing points and poor depiction of light and shadow mark many of Hitler’s paintings, but far from all of them. Perhaps we should not judge him by his worst work.

A paucity of people

Of course, not every one of Hitler’s paintings has glaring technical errors. He was selling paintings to tourists; perhaps he didn’t try that hard on everything. It’s hard to say, at this point in history; he was at least a competent amateur.

Hitler’s online proponents argue that any small technical errors he might have made are exactly the kind of mistakes that one goes to art school for. They don’t matter, his admirers say, because if only his talent had been recognized in his time, he would have learned to perfect his shadows and perspective.

Fair enough — except for the fact that he was applying to a competitive program. Much in the way that someone who aced chemistry in high school might not be admitted to MIT, being better than the average person at painting isn’t enough for an exclusive program. But, apparently having a rather high opinion of himself, Hitler didn’t apply anywhere else.

And the examiners at the Academy of Fine Art in Vienna didn’t just critique Hitler’s techniques; they criticized his underlying lack of care for humanity, complaining that his work didn’t feature enough humans. (When he did paint people, his technical issues were even worse; in one painting of Mary and an infant Jesus, Mary’s hand is hulkingly large.)

Hitler’s work on people was bad enough that, when he failed the entrance exam for the Academy of Fine Arts, the school’s feedback noted his lack of attention to humans. One examiner encouraged him to go back to high school, get his diploma and reapply to the school of architecture, since it was clear that he was more interested in buildings than in people — a prescient criticism.

Subjective subject matter

To be fair, realism isn’t always the aim in art. Many artists — like, say, Picasso — made a point of messing with perspective and proportion. Others, such as Rothko, stopped attempting to paint a literal object or person at all, and played with pure form and color.

But Hitler was not an abstract or modernist painter; in fact, as became clear later in his life, when he became Fuhrer, he abhorred any style of art that deviated from realism. His landscapes weren’t evocative expressions of, well, anything in particular, but instead attempts at true-to-life reproductions of what he saw.

This makes his technical errors more glaring and unforgivable, of course. And it also, probably, is why the art school rejected him. Not only was his realism not quite good enough, it was unfashionable and out of step with the cutting-edge experimentation of his time.

In the early 1900s, art was becoming groundbreakingly avant-garde. Artists were taking big risks in style and technique, and Expressionism, which emphasized emotion over realism, was booming in Europe. Monet was painting his water lilies with daubs of paint instead of careful, realistic details and Edvard Munch works with their thick lines and eerie colorings were beginning to gain critical attention. Picasso and Braque were skewing perspective and composition as they experimented with Cubism.

And in the very city where Hitler was applying to art school, a little over a decade before his first try, a group of Viennese artists, led by Gustav Klimt, had seceded from the Austrian artist’s association in protest of its emphasis on realism and historicism; they wanted to focus on the decorative style and bright colors that came to define the Art Nouveau movement.

Hitler’s works, meanwhile, kept to muted colors and carried few emotions; they focused on fussy details and careful reproduction with none of the conceptual breadth or experimentation that his contemporaries were using. His work, in short, was not creative or distinctive enough. (Perhaps that’s why there’s such a successful market for forgeries.)

Fascist art and classicism

For the people who love Hitler’s art today, its main appeal seems to be that it depicts pastoral European life — the kind of Aryan idyll that Hitler sold to the German people in his time, and that white supremacists still dream of. There’s no boundary pushing in these paintings, which is what makes them boring, but at the same time appealing and comfortable to conservative extremists.

Contrast these drab pastorals, as that viral tweet did, with Rothko’s bold color and abstract style. Rothko was highly engaged with his contemporary world, including theory and criticism — unlike Hitler, he didn’t turn his back on modernity to dream of an imagined past.

It’s a common complaint that anyone could make abstract art, that it’s unskilled. But Picasso painted classical portraits before Cubism, and Rothko painted evocative landscapes and buildings before he moved to abstraction.

The avant-garde artists wanted to access feeling and meaning in its purest form. “There is no such thing as good painting about nothing,” Rothko said; he was instead aiming at “the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea and between the idea and the observer.”

Perhaps understanding that his lack of meaning is part of what made him a failed artist, Hitler embarked on a campaign against what he called “degenerate art” shortly after he rose to power; he put on a mocking exhibition of modernist work, disparaged its supposedly Jewish nature, and burned masterpieces. The Nazis claimed this “degenerate art” would “endanger public security and order.”

Yet even in targeting the Expressionist and avant-garde, Hitler was, in a way, acknowledging their success; if the work aims to provoke a deep emotional response, it certainly got one.

Art may be in the eye of the beholder, but where most people at least online who respond to Hitler’s work might praise it as pretty or accurate, no one says they are moved by it, or that the art itself communicates a philosophy or idea.

Rothko’s art, on the other hand, provokes an emotion. Even if that reaction is anger or hatred, the work has succeeded exactly as Hitler’s failed.