Was the ‘Yiddish Sherlock Holmes’ the first Jewish superhero?

Detective Max Spitzkopf, now in English translation, gave Jews of the 20th century an avenger of their own

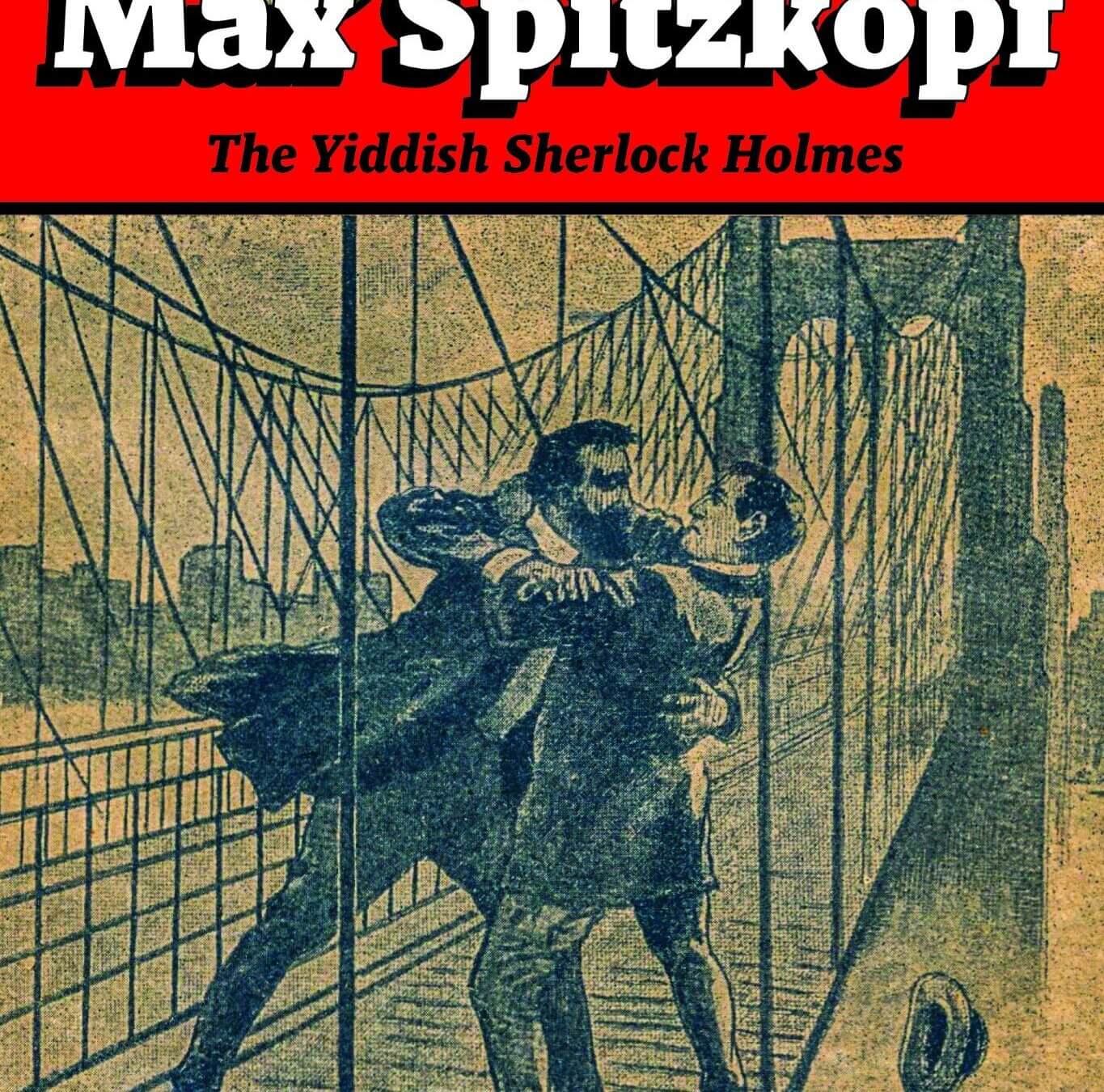

Spitzkopf tussles with an assailant on a bridge. Courtesy of White Goat Press

In 1908, around 30 years before Batman was first billed as the World’s Greatest Detective, and 15 after Sherlock Holmes solved his final case, another sleuth made his bombastic debut, rescuing a rabbi’s kidnapped granddaughter.

This hero distinguished himself in a major way. As the back blurb of his adventures insisted, “Max Spitzkopf IS A JEW — and he has always taken every opportunity to stand up FOR JEWS.”

The adventures of Spitzkopf, the nattily-dressed, pistol-brandishing Viennese gentleman, renowned throughout Austria-Hungary for his gumshoeing, were published in 32-page pulp pamphlets across the Yiddish-reading world. In his memoir, Isaac Bashevis Singer, vividly recalled devouring these stories as a child, and he was far from alone. Yet for all their popularity, copies of the original volumes, like Batman’s first appearance in Detective Comics #27, are exceedingly rare.

In 2017, Mikhl Yashinsky was a fellow at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, when it received the first five stories in a bound volume from a donor. They were in rough shape, their cheap paper crumbling. Yashinsky set out to translate them.

“He was really a kind of Jewish superhero,” said Yashinsky, whose full translation of the 15 Spitzkopf stories, written by Jonas Kreppel, is out now. (He received the other 10 from the Yale Judaica Library, one of the only institutions in the world to have the complete collection.)

The cases Spitzkopf and his capable Watsonian assistant, Fuchs, take on reflect the early 20th-century conditions of Jews in Galicia.

Spitzkopf uncovers a blood libel plot — and thwarts a Passover pogrom. He frees a young Jewish woman from sexual slavery in Constantinople. While Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories, which were translated to Yiddish, certainly had a literary edge on these mysteries, Spitzkopf was an avenger for his people. And whereas these Jewish cause célèbres rarely had a happy outcome, Kreppel, the author, always served up poetic justice. The writer was so sensitive to his readers, no doubt affected by the prejudice and violence he ripped from the headlines, he didn’t leave them in suspense, revealing the villains’ machinations early on.

While Spitzkopf is described in the translation’s subtitle as the Yiddish Sherlock Holmes, Yashinsky said the stories themselves are scanty when it comes to the character’s Yiddishkeit. The text itself calls him the “Viennese Sherlock,” and he appears to be a well-assimilated Austrian citizen, written in a distinctly German-inflected Yiddish. He is just the kind of person his creator aspired to be.

Kreppel, born into a Hasidic family in Drohobycz, Galicia, was a prolific writer on many subjects in four languages (Yiddish, German, Hebrew and Polish). He edited Jüdische Korrespondenz, a newspaper of German-Jewish concerns, wrote a still-used reference text on German Jewry, Juden und Judentum von heute (Jews and Judaism of Today) and countless political tracts. (He also published one-off, sensationalist adventure stories with titles like My Son-in-Law the Murderer.)

Initially poised for a rabbinical career, Kreppel settled in Vienna and eventually served the Austrian government as a press officer and advisor to the foreign consulate. Ever the patriot, and a defender of his fellow Jews, he was an early critic and victim of Nazism. The Nazis sent him to Dachau in 1938 and murdered him in Buchenwald on July 21, 1940.

Yashinsky translates the Spitzkopf stories with a flair reminiscent of gangster flicks. He also cites inspiration from his maternal grandparents, voice actors Elizabeth and Rubin Weiss, who performed a variety of roles on radio serials like The Lone Ranger and Challenge of the Yukon.

“They played those villains and damsels in distress,” said Yashinsky, himself an actor, who recorded a brief selection of the Spitzkopf stories for the current exhibition at the Yiddish Book Center.

The crooks Spitzkopf tracks down speak of “cheesing it” when they wish to make themselves scarce. Antisemitic Poles speak in heavy dialects of the loathed Żydzi they plan to blame for the death of a child before Passover.

The Yiddish literati of the early 20th century looked askance at Kreppel’s stories, deriding them as “shund,” originally a term for waste left after butchering animals. Yashinsky read that Yoel Teitelbaum, founder of the Satmar Hasidim, was scandalized that his words were “distributed far and wide as though they were Holy Writ.” Yashinsky believes they have value.

“To me, it’s important to take seriously the popular culture of the day,” Yashinsky said. “They’re stories of heroism and of sticking up for the persecuted and defending them. So I think that’s relevant in any time, and especially in ours.”

Perhaps it’s wish fulfillment, like the claims on every booklet that Max Spitzkopf was a man who “LIVES AND BREATHES.”

He didn’t do either, but those who read of his exploits likely felt better believing the lie.