What’s Under Your Fashion Exhibit?

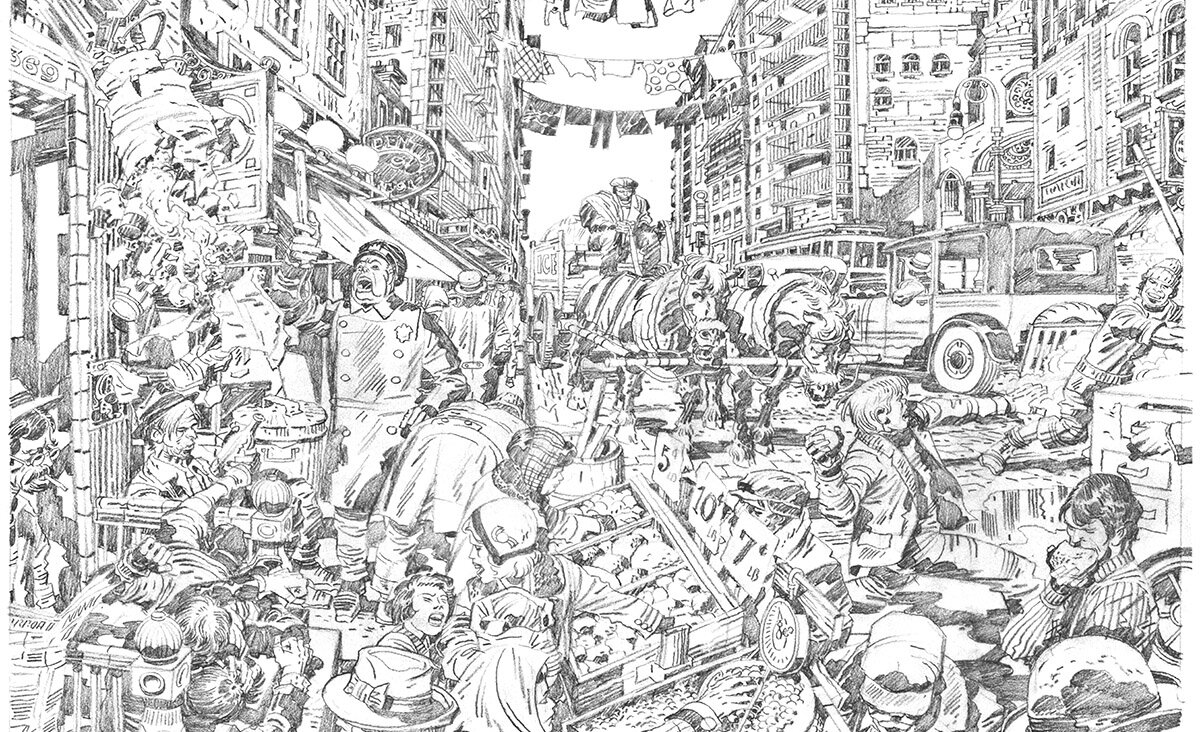

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

When the State of Israel first came into being 67 years ago, it harbored certain aspirations: It hoped to be not only a national homeland for the Jews and a light unto the nations, but also the fashion mecca of the Middle East. Most of us are familiar with the first two beau ideals; the third may come as something of a surprise. We don’t usually associate the Holy Land with high fashion.

Still, it wasn’t for want of trying. Both Hadassah and ORT quickly established vocational schools to train a future generation of designers. Established garment manufacturers from the United States also lent a helping hand. Thanks to their encouragement and the steady development of a homegrown textile industry, “Israeli fashion is conquering the world,” jubilantly proclaimed an economics reporter in 1951, as he took the measure of its products at international expositions.

Gottex, the manufacturer of boldly patterned and inventively designed bathing suits and swimwear accessories, helped to put Israeli fashion on the map. Under the imaginative direction of Lea Gottlieb who, together with her husband, relocated to Israel in the wake of the war, Gottex became an internationally renowned brand. Some of its dazzling designs are currently on display in a rather modest exhibition at the JCC of Manhattan called “What’s Under Your Pareo? Unraveling the Work of Lea Gottlieb.” A loan show from the Design Museum Holon, it showcases a number of swimsuits and cover-ups alongside a series of sketches and snapshots.

Wrap Star: ‘What’s Under Your Pareo’ at JCC Manhattan spotlights Lea Gottlieb’s designs. Image by Koon JCC Manhattan

The exhibition traces the influences that fired Gottlieb’s creativity. The local topography, especially its marine life; the needlecraft traditions of Gottlieb’s native Hungary; Monet’s flowers; Chagall’s use of blue; and the impact of an exhibition at the Louvre on Nefertiti actively shaped her visual imagination. It would be lovely to think that “What’s Under Your Pareo?” would have a comparable effect on future designers, inspiring them to similar heights. Alas, much like its subject matter — the bathing suit — the exhibition is far too scanty for that. Would it be otherwise.

The story of how the nascent state of Israel reconciled the contempora-neity of fashion with the imperatives of tradition is a fascinating one and deserves its place in the sun. Visitors to the JCC exhibition would be intrigued to learn that what to cover and what to expose was a source of great concern during Israel’s formative years. As Anat Helman, an historian at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, makes clear in her lively and compelling book “A Coat of Many Colors,” dress loomed large on the national agenda between 1949 and 1956.

If, in the United States of the postwar era, what to wear was largely a matter of individual taste, in Israel of the early 1950s, what to wear was a collective preoccupation. Army quartermasters, kibbutz residents, administrators at the Ministry of Rationing and Supply, let alone readers of Haisha, had much to say about the cut, fit and meaning of contemporary attire.

In some instances, Dame Fashion took her cue from the weather, which rendered so much of Western fashion downright impracticable: too hot, too cumbersome, too fussy. In other instances, she deferred to the dictates of religion, which frowned on novelty and favored modesty. Meanwhile, the influx of thousands of immigrants from the East, who were not so quick or eager to exchange their native dress for Western attire, further complicated fashion’s hold on the body politic.

Gottex: Lea Gottlieb's internationally renowned brand, Gottex, is on display at the JCC of Manhattan. Image by Koon JCC Manhattan

The culture of casualness, which dominated so much of Israeli culture, also gave Dame Fashion a run for her money. The emphasis Israelis of the 1950s placed on informality, verging close to austerity and even renunciation, didn’t take kindly to the frivolity associated with the pursuit of stylishness. When, in 1954, a high priced clothing store that carried American teenage fashions opened in Tel Aviv, it was roundly criticized. “There’s no room for such a salon in Israel,” insisted its detractors. “We have not yet become a people that can allow itself only the concern for beauty and prettiness. Our youngsters have other missions and other occupations. Any such salon is an alien element in our midst.” Even the military had to tailor its uniforms lest they smack too much of stiff upper-lip, Western notions of sartorial protocol. Constituting itself an “army of the people,” the IDF was determined to look the part.

It would take years — by one account, nearly 500 of them — before Israeli fashion came into its own. Helman tells us that those in the garment business who were unwilling to wait so long “nationalized” their offerings by bestowing upon them a local name: A fur chapeau dubbed the “El Al” was just one of many such examples that enliven Israeli vernacular history; a forward-looking ensemble labelled the “Negev-colored” suit a second. Meanwhile, other members of the fashion world sought to push things along by developing a line of clothing expressive of “Sabra simplicity, Eastern colorfulness and Western sewing technology.”

Did they succeed? A look into our closets, jewelry boxes and shoe bags provides the answer. We didn’t have to wait an eternity, after all.