History of Dutch Jews Role in Slavery Is Bluntly Depicted

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

‘The word ‘slave’ is used in this exhibition,” notes a wall text at “Jews in the Caribbean: Four Centuries of History in Suriname and Curacao” at Amsterdam’s Jewish Historical Museum. “The museum is aware of the controversial nature of this term. ‘Slaves,’ as used here, refers to African men, women, and children taken captive and sold as slaves and their descendents who were born into slavery.”

That Jews have owned slaves, despite biblical injunctions about caring for the disadvantaged and the Passover focus on liberation from servitude, isn’t an unknown narrative. The bible itself refers often to laws governing both Jewish and non-Jewish slaves. But it is rare for an exhibit at a Jewish museum to so bluntly and thoroughly address the topic as this show does. (A notable exception: the 1961 Jewish Museum exhibit “The American Jew in the Civil War.”)

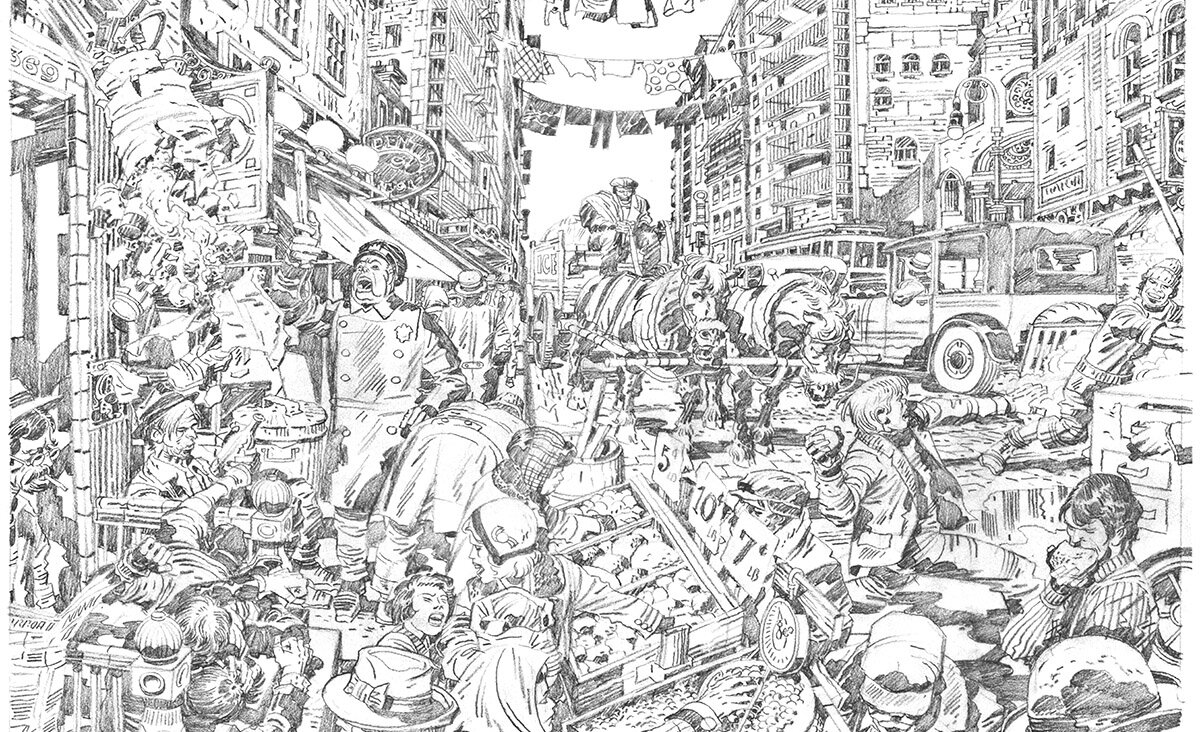

A watercolor by German (non-Jewish) clerk Zacharias Wagenaer, who later rose in the ranks at the Dutch India Company, depicts a slave market in the Brazilian city of Recife. A triangular perspective of a street — which the exhibit notes was home to the Portuguese Jewish congregation’s first synagogue — circumscribed by Cape Dutch architecture, Wagenaer’s painting shows several wealthy figures in doorways, looking out of second-story windows, and milling about the slave market.

Where Wagenaer teases out details in the clothing and facial features of the buyers, the majority of the African slaves are depicted as nondescript masses — more like insects than humans. The few slaves that Wagenaer represents specifically are in vulnerable rather than heroic poses.

“A few days after their arrival, slaves were sold here to Dutch and Portuguese Jewish merchants,” an exhibition wall text notes of Wagenaer’s illustration, one of very few representing the slave trade. Half of the slaves died from hunger and thirst en route to Brazil, according to the exhibit catalog.

Elsewhere in the exhibit, a contract signed on January 6, 1673 — from the Amsterdam City Archives — details the commitments of Emanuel Alvares Pinto (who came from a Marrano family), Pieter van Rendorp (who wasn’t Jewish), and other ship owners to supply 400 slaves to Curaçao. In 1662, Spanish authorities gave two bankers, Domingo Grillo and Ambrosio Lomelin (neither Jewish), a monopoly on the slave trade to Spanish America, and between 1663 and 1667, roughly 3,600 slaves were transported from Curaçao to the Spanish territories.

Yet another wall text in the exhibit discusses the Suriname synagogue Beracha VeShalom in Jodensavanne (Jewish savannah). It notes that Jews were given special dispensation to work their slaves on Sunday instead of Saturday.

Dutch Jewish activity in the Caribbean, beginning with the arrival of Dutch traders in the 1500s, has been much discussed in scholarship, according to Robert Taber, an instructor of Latin American history at University of Florida.

“Slave ownership came with the territory — no major religious tradition had prohibitions on African slavery until around the 1770s. If a person lived in the Caribbean and had any amount of wealth at all, they would use it to rent or buy slaves,” Taber says. “This was a constant across empires, across religions, and across races — as free blacks and people of color also often owned slaves.”

Scholars, therefore, don’t consider Dutch Jews’ ownership of and trading of slaves particularly scandalous or shocking, nor was it considered so at the time. “In some ways, this general acceptance of slavery at the time is horrifying, because it prompts some serious thinking about what we might do on a regular basis that is grossly exploitative,” Taber says.

Museums, as well as institutions which played a role in selling slaves, have more recently begun commemorating slavery. “A major concern in museum studies has been to include participation from the people being represented, to let those ‘under study’ speak their own story,” Taber says. “This museum exhibit may show the merging of these two trends: The Jewish Historical Museum is providing space for Jewish people from Curaçao and Suriname to tell their stories. Hopefully, they want to account for the role of Dutch Jews in these Caribbean slave societies.”

Menachem Wecker is co-author of “Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education,” published by Cascade in 2014.