Inside Sasha Velour’s Talmud of Drag

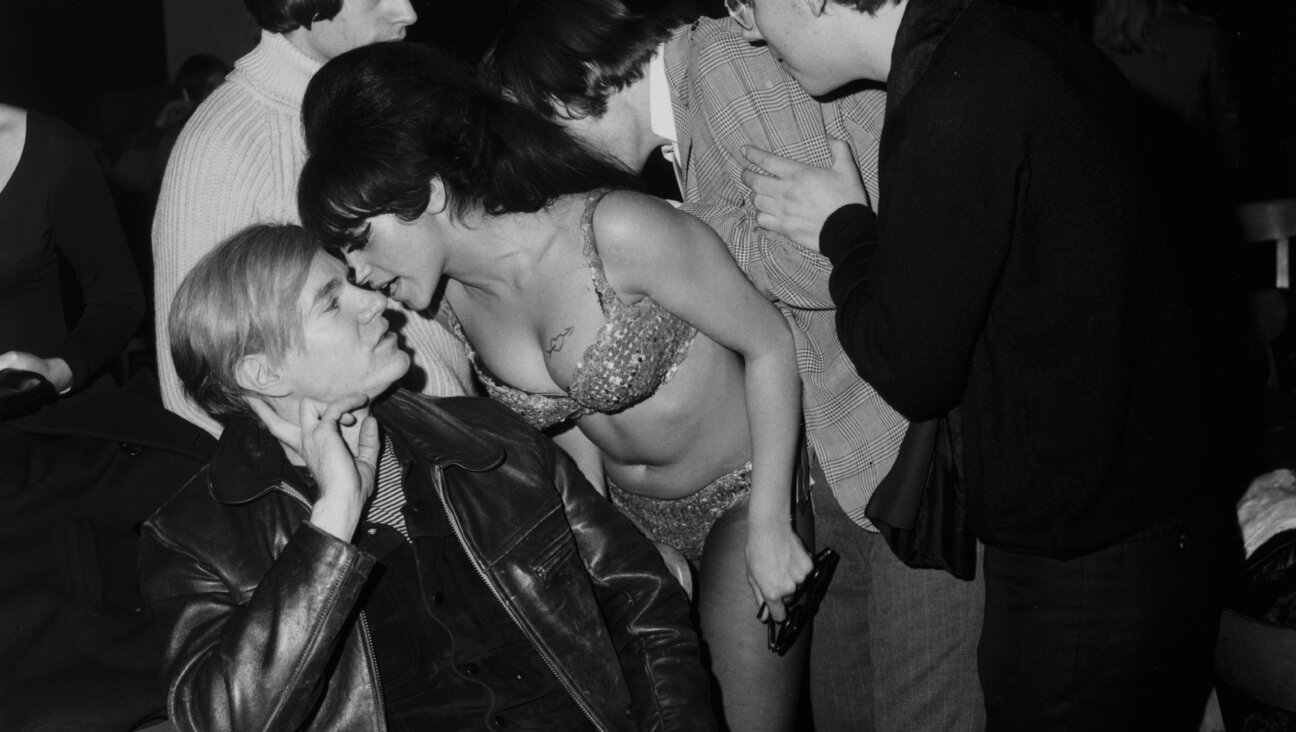

Image by Courtesy of Sasha Velour

The Talmud didn’t make Sasha Steinberg a drag queen. But it did help inspire Vym, the “drag culture” glossy he launched in July as Sasha Velour, his alter ego.

“What struck me about the Talmud, and so much Jewish philosophy, is that it’s not always one narrative,” Steinberg told the Forward from the Brooklyn apartment he shares with partner and Vym co-founder John Jacob Lee, an actor. “It’s different voices interpreting and reinterpreting these texts. Vym is the same. Discussions of gender, queer history and queer politics shouldn’t always be in agreement.”

Vym Magazine: Sasha Steinberg, aka Sasha Velour, recently co-launched ‘Vym,’ a glossy magazine about drag culture. Image by Courtesy of Sasha Velour

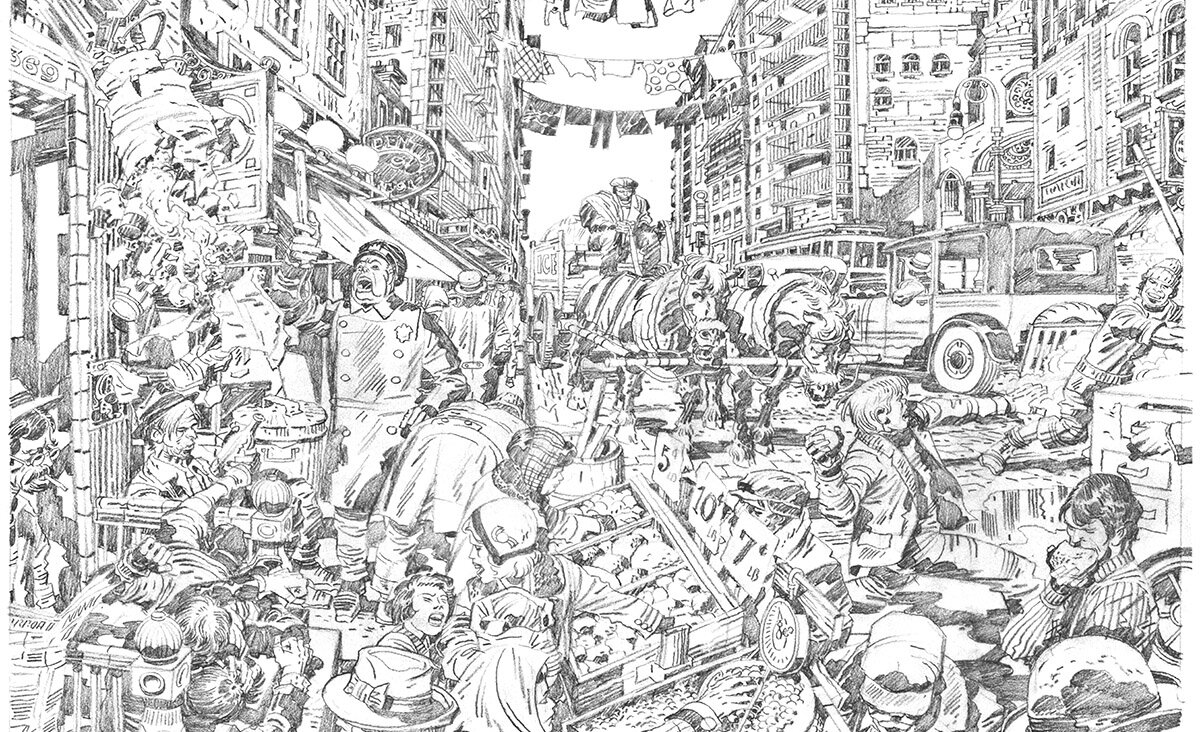

In an “art magazine about drag,” Vym uses “philosophy, photography, comics, and illustration to explore what it means to do drag,” Steinberg said. “It’s not just a series of random interviews with drag queens, but an exploration of what drag is about, what it can be, its history.”

Even in the age of “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and very public dialogue around gender, drag retains its subversive power, said Michael Musto, who is an author, a columnist for Out magazine and a longtime chronicler of New York nightlife.

“Drag is now a household word,” Musto said. “But it will always be subversive because the act of a man dressing like a woman has an edge that can’t be dulled by massive exposure.” As for Vym’s prospects, “there is an audience for it,” Musto said. “Drag lends itself to creative exploration of many kinds, and taps into people’s imaginations and fantasies. Besides, a lot of drag queens are artists, so this will give them a great venue.”

Steinberg and Lee raised $8,000 on Kickstarter to launch Vym, offering donor perks like on-demand lip-syncing videos, and “dragged-up” photo shoots — one of which was bought by “a middle-aged mom,” he said, laughing. “We figured everyone can experience drag as perfomative, so why not?”

Steinberg’s heady approach to drag reflects his polymath background. Born in Illinois to Mark D. Steinberg, a labor history professor dad, and to a “Daughters-of-the-American-Revolution Protestant” editor mother, Jane Hedges, he lived all over the world while his family schlepped “from university to university.”

As a child, he was allowed to choose which family tradition to follow — “a very strange liberal-childhood experience,” he said. “I chose Judaism, mainly because of the stories and the food. And I felt a strong connection with that side of the family, since I have a Russian name. Their history felt vibrant and personal.”

One set of Steinberg’s paternal great-grandparents survived the Triangle Waist Company Fire and traveled “back and forth between America, Ukraine and ultimately Harbin, China, becoming merchants, truck drivers, garment makers.” The other set was reputed to have killed a brother; the name Steinberg “was picked as an alias” when they went on the lam.

“Identity for Jews like us was shaped by cultural practices and family traditions rather than allegiances of place or language or class, because those things continued to be redefined for us,” Steinberg said. “Drag operates along similar lines. As a drag performer, my identity exists in music, art and fashion, not in any one ‘language’ of gender or ‘appearance.’”

After high school in Illinois, Steinberg lived in Russia and then Germany, where he volunteered at the Berlin State Opera. Back in the United States he studied theater and literature at Vassar College, focusing on translation, which became a kind of metaphor for his life. “Translation became a philosophy for not just thinking about language and culture, but about gender, and how we distill ideas into our own bodies and experiences,” he said. A Fulbright scholarship took him to Russia, where he aimed to study the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender movement, though to get the project approved he told the Russian government it was about “political art.”

A Matter of Identity: Sasha Velour's new magazine about drag culture was inspired, in large part, by Jewish philosophy. Image by Courtesy of Sasha Velour

But Steinberg found that the ivory tower was creating a barrier. “In Russia, I kept trying to explain these complicated ideas. The kind of writing I’d learned to do was not helpful,” he said. Then he discovered comics. “Comics are an incredible vehicle to deal with really complex issues. They’re so much more accessible than academic writing,” he noted. Steinberg ended up in River Junction, Vermont, pursuing a master’s degree in cartooning at The Center for Cartoon Studies.

“I went to Vermont to learn how to translate my ideas about gender identity and queer history into comics form. Vym is a kind of comics project at its heart,” Steinberg said. Steinberg’s own comics include witty, wry work about the Stonewall riots and “a queer Agatha Christie-ish mystery” called “The Disappearance of Pepper Stein.”

Sasha Velour herself began life as a comics character before Steinberg felt bold enough to take her onstage. His performances became riskier and bolder; a kind of horror-chic Nosferatu drag is now his signature.

With the launch of Vym, Steinberg’s Jewish and drag identities are finally intersecting in more meaningful ways. “The connection between the malleable identities of Judaism and of drag is really interesting to me, he said. “In terms of my own family, Diaspora has always been about repeated and dramatic reinvention.” The magazine is a family affair as well; Steinberg’s mother, Hedges, who later died of cancer, copy edited it.

Not all of Vym’s contributors are drag queens, or have even been immersed in drag culture. Masha Bogushevsk a New York-based photographer, met Steinberg when the latter started teaching at Be Fluent NYC a language school she owns in midtown Manhattan. She ended up documenting his transformation from Steinberg to Velour over six radiant pages shot at the apartment that Hedges and Steinberg share.

“I’d seen Sasha — this soft-spoken employee and teacher — become a very big character onstage,” said Bogushevsky, the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants. “It’s almost like his body size changed. I was amazed at his confidence and how he carried himself. And I wanted to capture that.”

Steinberg says that kind of power fuels his art. “For me, being really strong in my character means being confidently weird,” he said. “That’s really important. My whole life, people who’ve done that have really inspired me. And that’s absolutely a Jewish idea.”

Michael Kaminer is a contributing editor at the Forward.