The Jewish Community Still Discriminates Against Bastards. These Artists Are Demanding Change.

Image by Courtesy of the Jerusalem Biennale

Inside a small room in Jerusalem, four artists are taking on one of the most deep-rooted taboos in Judaism: That of the mamzer, the illegitimate child.

A mamzer is someone born as the result of a sexual relationship forbidden in the Torah. Translated in English as “misbegotten” (according to the JPS Tanakh, but also commonly known as a “bastard” or “illegitimate child”), a mamzer is a child born to a married woman fathered by a man other than her husband or a child born from an incestuous relationship. Not only does Jewish law prohibit a mamzer from marrying other Jews (mamzerim are only allowed to marry other mamzerim or other converts), but the prohibition is also passed on for ten generations, which is to say, for all generations.

Four Israeli artists, Nurit Jacobs-Yinon, Andi Arnovitz, Ken Goldman, and Mira Maylor, are challenging Jewish society to reconsider the Jewish law through their exhibition, Mamzerim: The Misbegotten.

Advocating against these ancient laws, the co-curators of the exhibition explain that Mamzerut [illegitimacy] is an ongoing human tragedy taking place within Jewish and Israeli society that remains largely unknown. “I started this project about Mamzerut because it is not just an Israeli or Jewish issue, but a human rights issue,” said Jacobs-Yinon. ”It’s a huge problem, and we need to talk about it.”

The modern challenges of interpreting the concept of Mamzerim are wide ranging but immediate. In Israel, there is no separation between church and state, so the halakha (Jewish law) of the mamzer has received legal status in the State of Israel. Furthermore, the Chief Rabbinate, acting as an executive arm of the State of Israel, is maintaining a secret and computerized database of those forbidden from marrying, known as the ‘Blacklist’. As of September 2017, the Israeli press reported that the Chief Rabbinate has an active blacklist of those prevented from marrying other Jews, and that the list included 6,787 names.

Andi Arnovitz was so horrified and moved by the existence of the blacklist, which she discovered just a few years ago, that she spent two years creating her own artistic response with The Black List by wrapping, winding and tying thousands of black Japanese papers into 6,386 scrolls, and keeping the contents hidden. She piles the scrolls on a metal pedestal, like a sacrifice. “I thought about how these people are all being sacrificed in this power war and in the ‘name’ of halacha and decided they would be symbolic korbanot (religious sacrifices).” As an Orthodox Jewish feminist, Arnovitz is constantly creating art about the intersection of biblical law, Jewish rituals and feminism. “What was once a humane halachic system, devised to protect and preserve, has now been perverted … where the powerless are systematically abused/isolated and rejected by these rabbis,” she says. Arnovitz is just one of many Orthodox Jews against the modern application of Mamzerut in contemporary Jewish society.

While not a mamzer herself, Jacobs-Yinon is a filmmaker and video artist who closely identifies with those struggling with “who is in and who is out” of Judaism, as a convert. She uses her art as a vessel to bluntly discuss the topics that are usually not discussed at all. When entering the exhibition, one is confronted with a multi-part installation complete with legal documents, a video recounting 12 personal testimonies of anonymous mamzerim, and an interview with a woman who details her experience giving birth to a mamzer. It is both unsettling and unsurprising to learn the legal, social, and religious aspects of life a mamzer and then being excluded from the Jewish community today.

Similarly, Mira Maylor’s work, Transparents, directly confronts visitors to ponder the feeling of being an outsider, an invisible Jew. You can’t escape your own reflection as you observe each of the glass heads mounted on a background mirror. “I always hope that my work will be bothering enough for people to get out of their comfort zone and think. Even a little deviation out of their comfort zone is good for me.”

Surely art can be a springboard for activism, but how do we change problematic laws that some people do not see as problematic and have no desire to change?

Activists from all religious sects are working hard in Israel to override this taboo. Feminist activist and attorney, Susan Weiss, is fiercely trying to demystify the stigma of mamzer and change the current Israeli legislation. She founded Center for Women’s Justice, and writes in her essay, “Women, Divorce, and the Mamzer Status in the Israeli State,” that her goal is “to urge the state of Israel to reject all legislation, regulations, and courts that support its unfortunate notion and the witch hunt that it has, perhaps inadvertently, engendered.”

To be sure, there are sects of Judaism that do not subscribe to the laws of Mamzerut.

Weiss references Conservative Rabbi Elie Kaplan Spitz who refuses to consider any evidence of Mamzerut. “We will give permission to any Jew to marry and will perform the marriage of a Jew regardless of the possible sins of his or her parent,” he wrote in a 2000 paper “Mamzerut.”

Nevertheless, there are many Orthodox leaders who believe the laws will not be overturned anytime soon. “Frankly, the laws of mamzerut still apply to Torah-observant Jews and I see no reason to alter or pretend to alter the basis of these ancient laws,” said Rabbanit Chava Evans.

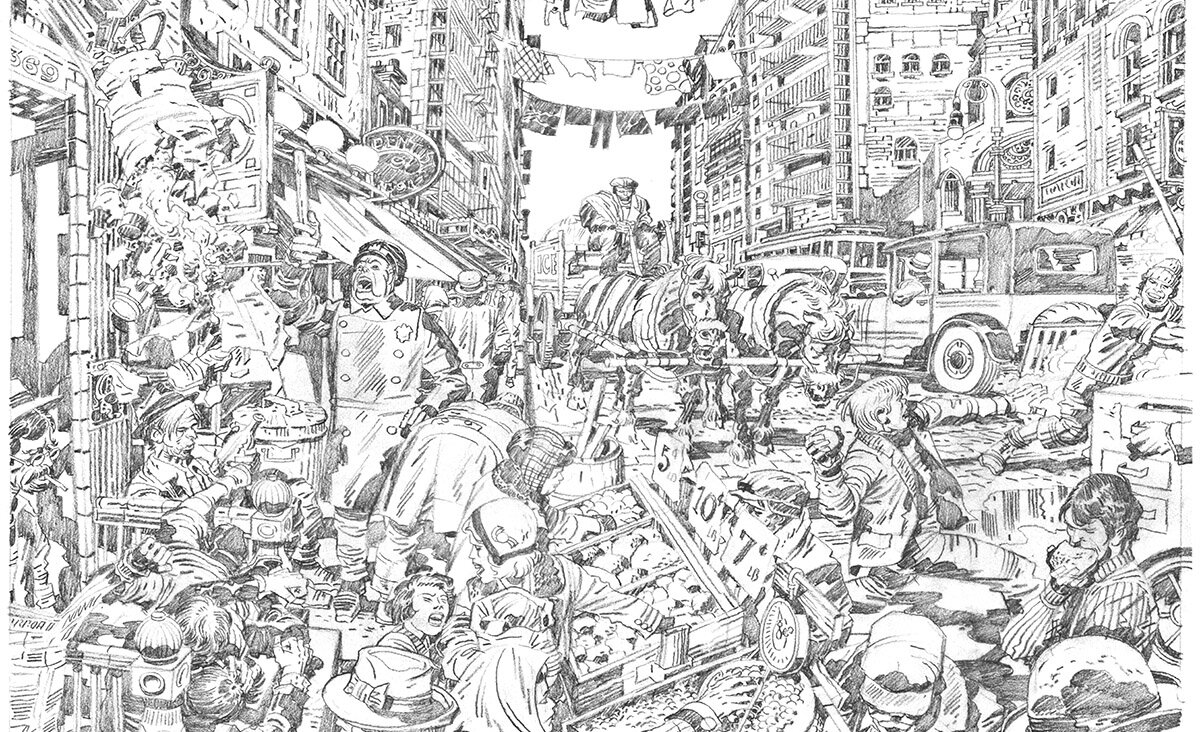

Like Arnovitz, Ken Goldman explains that he has been haunted by the subject of mamzerim so much so that he created DNA Huppah. In the center of the exhibition space, a wedding canopy printed with the pattern of DNA is hung from the ceiling. Emily Bilski explains that having a chuppah in the exhibition was very important when she and Jacobs-Yinon selected Jewish art for the show, especially since “the issue of halachic marriage is at the crux of the mamzer issue.” Exclusion from Jewish marriage is also exclusion from Jewish DNA.

The group show is just part one of this artist-activist journey.

Advocacy for this issue goes beyond art exhibitions, too. Jacobs-Yinon and Bilski just released Mamzerim: Labeled and Erased, a bilingual (Hebrew-English) book of academic essays, modern midrashim and artistic images, in an effort to raise public awareness and combat the modern application of the mamzer. A documentary film about mamzerim, is also in the works.

Jacobs-Yinon tells me that she is sure the only solution will come through when everyone – not just Israelis – speaks up.

Perhaps the most striking part of Jacobs-Yinon’s installation is her projection of the biblical text (Deut 23:3) condemning mamzerim. Phrases like “No one misbegotten shall be admitted into the congregation of the LORD; none of his descendants, even in the tenth generation, shall be admitted into the congregation of the LORD” are projected from a video screen, across the floor of the gallery, casting itself onto the visitors.

Jacobs-Yinon cleverly implicates everyone as a participant in the conversation; no one is exempt or untouched by the laws of the mamzer.

Mamzerim: The Misbegotten is on view at the Bezeq Building (Chopin 12, Jerusalem) through November 16th as part of the 3rd Jerusalem Biennale. The book, Mamzerim: Labeled and Erased, launches on Sunday, October 30th, and is available for purchase here: www.mamzerim.com