Leonard Cohen’s Depth, Style Shortchanged By Montreal Tribute Exhibit

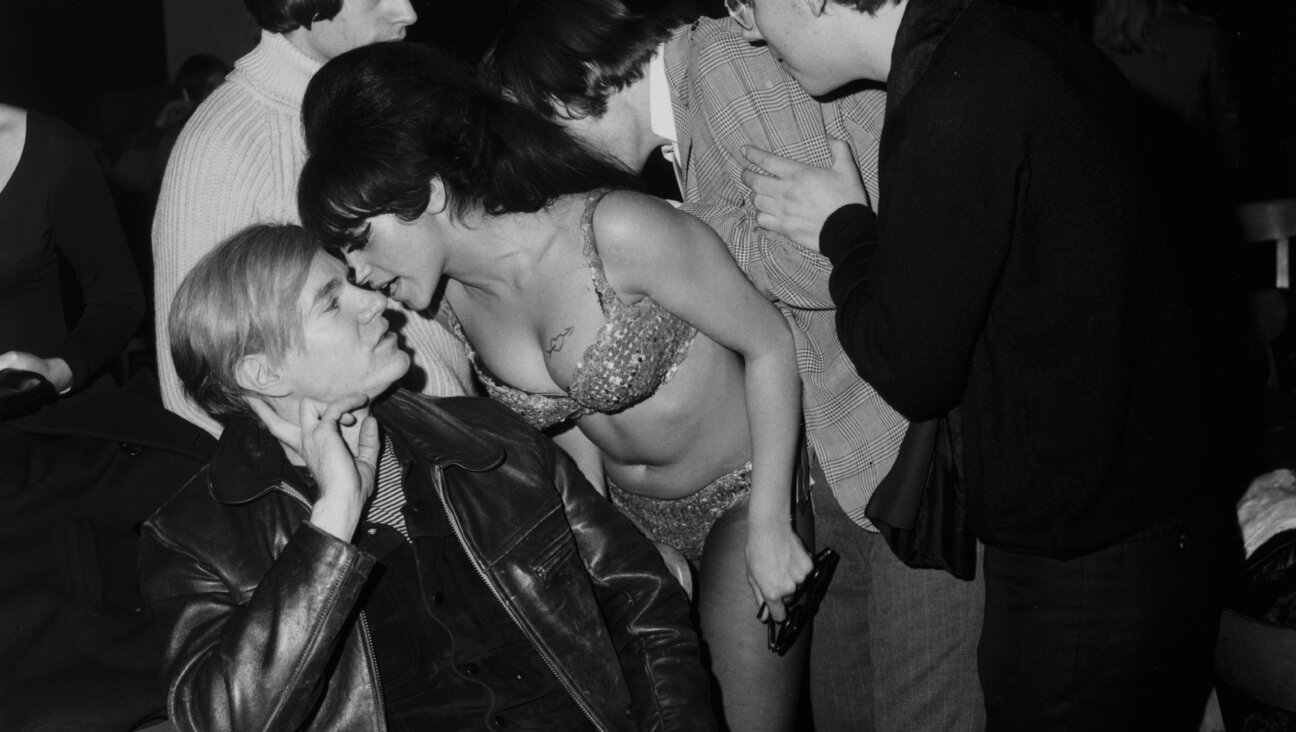

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

A Mona Lisa grin became one of Leonard Cohen’s signature facial expressions. For a poet of self-mocking intimacy, it made a perfect mask.

As I walked through “A Crack in Everything,” the new exhibit about Cohen’s life and work at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, I imagined Cohen appraising the show with that half-smile. Planned years before Cohen’s death as a multimedia tribute, the exhibit consists of artistic responses to Cohen’s work, including works from art world stars like sound-installation duo Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, filmmaker Tacita Dean and multimedia artist Taryn Simon.

For an exhibit about a supreme ironist, much of “A Crack in Everything” feels painfully earnest. How would the songwriter of “Bird on a Wire” react to Dean’s three-minute video of, ahem, a bird on a wire – it flies off at the video’s end – except to smirk?

The 15 other artistic responses to Cohen included in the show range from the literal – say, George Fok’s immersive (and superfluous) video installation of Cohen’s interview clips and TV appearances – to self-consciously hip projects like Kota Ezawa’s groovy but empty cartoon of an early Cohen television interview. Some nuanced, sharp-edged works feel closer in spirit to Cohen’s own, but those are outnumbered by high-concept, sometimes facile presentations.

“This was never a sycophantic exercise,” John Zeppetelli, the museum’s director, told a packed press conference on the day of the exhibit’s opening. “It’s not about his magnificently cut suits or fedoras. It’s about his incredible cultural output.”

“A Crack in Everything” opens with two installations inspired by “Hallelujah,” Cohen’s most relentlessly covered song. “I Heard There Was a Secret Chord,” a “participatory humming experience” by Montreal interactive studio Daily tous les jours that verges on self-parody, places spectators in a chamber that vibrates as participants around the world live-stream their own chants. What could have been a sly commentary on the song’s ubiquity – is there a reunion or death scene on TV that hasn’t used it? – becomes a “kumbaya” moment at which Cohen himself might have laughed.

Simon phoned in “The New York Times, Friday, November 11, 2016.” The piece consists of a glass case displaying the front page of The New York Times from the day of Cohen’s death. Above the fold, President Obama shakes hands with Donald Trump, the new president-elect. The juxtaposition – Trump atop the page, Cohen’s obit below – certainly jars the viewer, but only in the way reading an especially eventful front page would. The piece doesn’t transcend its material.

In “Ampel/Stoplight,” German artist Thomas Demand synchronized video of a stoplight to Cohen’s “Everybody Knows.” Appealing on their own, the parts never connect as an effective whole. Candice Breitz, a South African artist based in Berlin, offered “I’m Your Man (A Portrait of Leonard Cohen),” video footage of an amateur choir of Montreal-based Cohen devotees singing a litany of his songs. The piece is likely intended to capture the deep meaning of Cohen’s music to his fans; it puts forward the idea that his songs now belong to all of us. But hearing the chorus’s version of “Jazz Police,” one of Cohen’s weirdest compositions, just made me crave the original.

In fact, two of the show’s most effective installations aren’t by artists, but by the man himself – sort of. Along the walls of one corridor, the museum displays lyrics to ten of Cohen’s songs. Seeing his words displayed as art magnifies their already immense power. And a video cycles through Cohen’s self-portraits, ranging from doodles to more elaborate artwork. They’re funny, often self-mocking, and provide a privileged window into what made Cohen such a singular character.

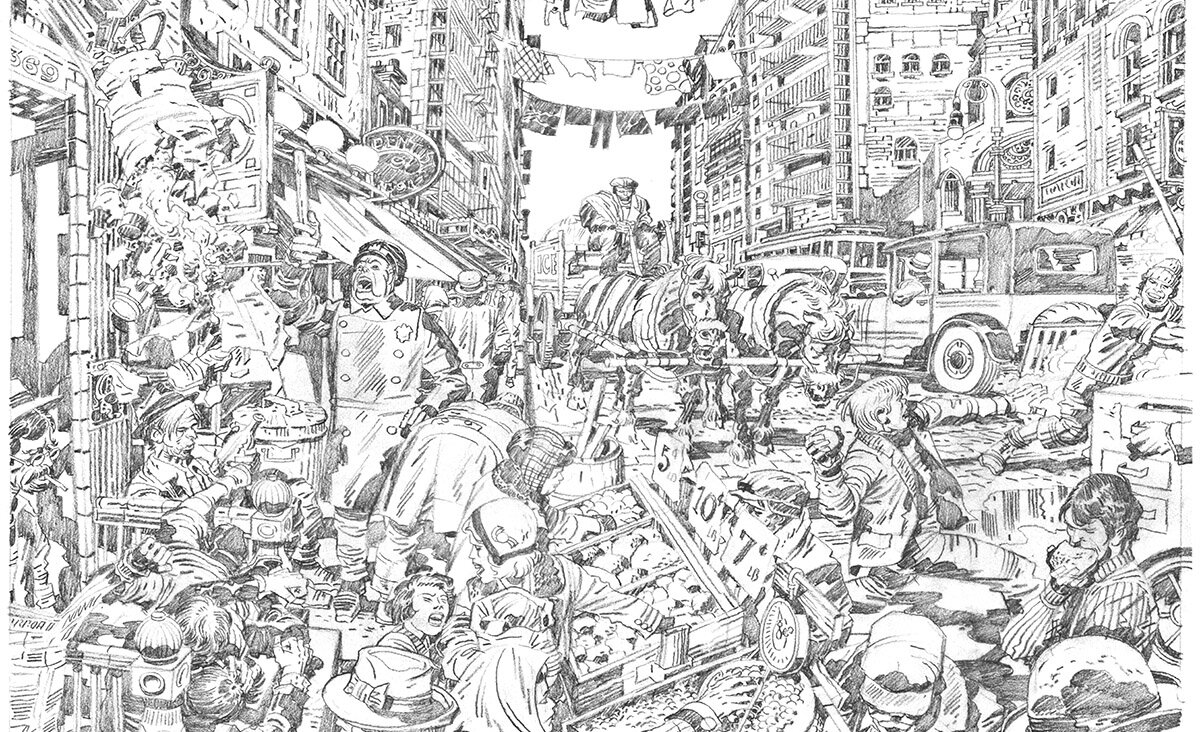

When the exhibited artists practice the same ironic distance to which Cohen himself adhered, the show loosens up. In his first museum work, Israeli filmmaker Ari Folman of “Waltz With Bashir” fame transforms what the “addictive melancholy” of Cohen’s songs – as Folman put it at the opening press conference – into the exhibit ’s most mordantly funny work. Folman’s “Depression Chamber” allows one viewer at a time to enter a darkened room in which a crazy quilt of animated symbols, including crosses, pinups, birds and tombstones, swirl and coalesce along the walls and floor to strains of Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat.” Folman told the press gathering that his sister’s teenage depression over an indifferent boyfriend inspired the piece. While acknowledging the music’s undeniable power, Folman also used the work to poke sly fun at the operatic grandeur of teen angst.

Just a few of the works in the exhibit revolve around explicitly Jewish themes. Chicago artist Michael Rakowitz, whose work focuses on notions of Jewish identity and geography, created a fantasy narrative around Cohen’s 1973 Yom Kippur War performance in Israel. In “I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze,” a video projection of Cohen’s legendary performance casts an eerie glow over display cases holding ephemera connected to that war and Rakowitz’s Iraqi-Jewish family history. Using Cohen’s own typewriter, which Rakowitz bought from a Berlin collector in 2013, the artist typed a long letter to Cohen that explores Jewishness and personal identity; the eight-page letter is displayed within the cases.

The most potent artwork in “A Crack in Everything” harnesses Cohen’s voice – literally – to devastating effect. For “The Poetry Machine,” Cardiff and Bures Miller have rigged a beaten-up organ to mismatched speakers that span the large, loft-like space. By holding down keys on the organ, visitors can launch different recordings of Cohen’s voice incanting his poetry and prose. Pressing multiple keys, his voice becomes a storm of words that dissolve into in an incomprehensible baritone. The second the keys are released, the voices stop. That moment, more than any in the show, drove home the magnitude of Cohen’s loss.

Before I left the museum, I asked Zeppetelli what he wanted visitors to take away from “A Crack in Everything.” “I hope they’re enriched and moved by this man’s enormous achievements,” he said. “People understand he’s great. We want to make that demonstrable with this show.” The show does make one thing clear: Cohen still outshines everyone around him.

“Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything” runs at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal through April 9 2018