For decades, a Jewish family has sought the return of their beloved painting — can the Supreme Court make that happen?

A Question of Ownership: Camille Pissarro’s “Rue Saint-Honoré, dans l’après-midi. Effet de pluie” Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons/Getty Images

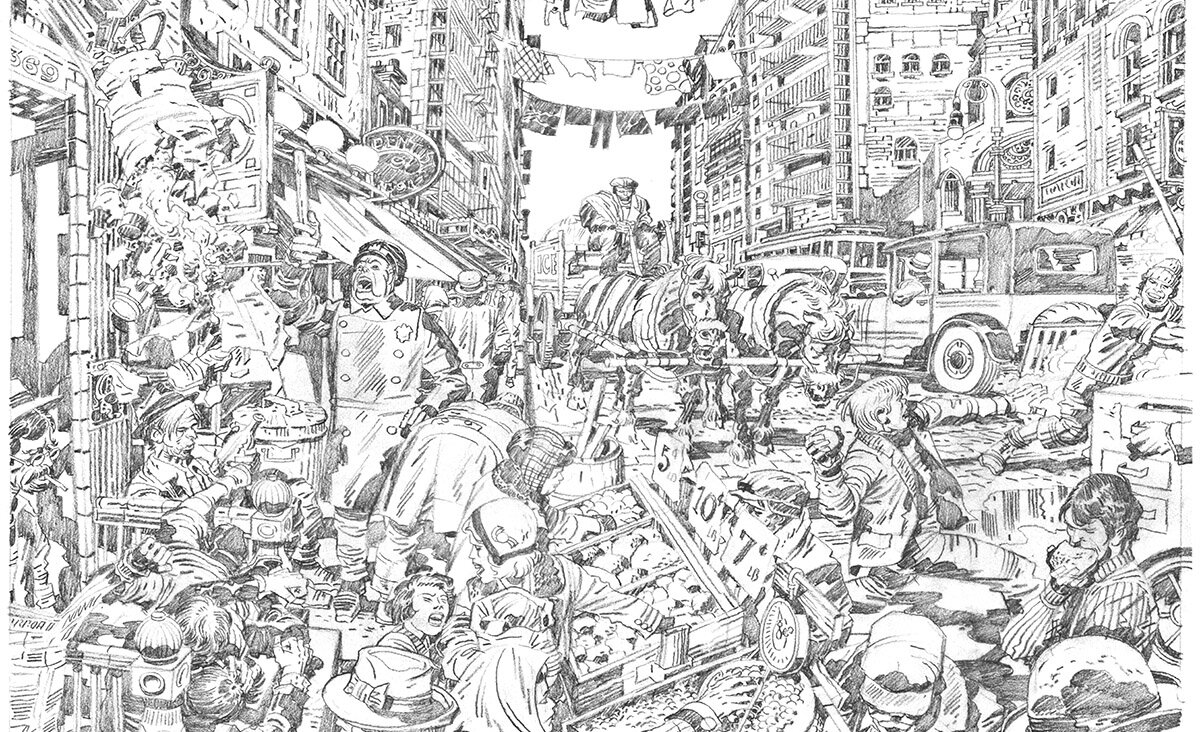

Twenty-two years ago, photographer Claude Cassirer received a call he never expected. His family’s long-lost Nazi-looted painting by the French-Jewish painter Camille Pissarro had been found. It was hanging in a Spanish museum. The painting, “Rue Saint-Honoré, Apres Midi, Effet de Pluie” depicts the grand avenues of modern Paris glistening during an afternoon rain. It was a prized possession of Claude’s grandmother, Lilly Cassirer.

Claude vividly remembered the painting, under which he would play with his toys as a child. An old family photograph shows the painting in Lilly’s Berlin apartment, prominently displayed in a gilded frame above a lush velvet settee.

Since the painting was discovered at the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum in Madrid in 2000, the Cassirers have been fighting to regain it. On Jan. 18, the painting will take center stage at the United States Supreme Court. At stake is more than the painting itself, now valued at over $30 million. The court could set new legal precedent as to whether looted art cases involving foreign nations will be determined under state or federal common law, and therefore whether a foreign nation’s laws on property trump both U.S. state laws and international doctrine.

If the Supreme Court concurs with the lower courts, which sided with Spain, it could lead to a chilling effect in looted art cases brought against other countries and embolden current holders of Nazi-plundered art. It is a tipping point for one of the longest-running cases about looted art in United States history.

Kunst Und Kunstler: Julius Cassirer was the patriarch of a family of cultural influencers, who made their fortune in manufacturing building construction materials. Julius’ son Bruno and nephew Paul established an art gallery and publishing house that produced art journal Kunst und Künstler, which was later shut down by the Nazis. By Wikimedia Commons

Art is in the DNA of the Cassirer family. In 1898, within just a few months of the completion of “Rue Saint-Honoré, Apres Midi, Effet de Pluie,” the painting was purchased by Claude’s great-grandfather, Julius Cassirer. He was the patriarch of a family of cultural influencers, who made their fortune in manufacturing building construction materials. The same year, Julius’ son Bruno and nephew Paul would establish an acclaimed art gallery and publishing house that would produce the well-known art journal Kunst und Künstler. Bruno and Paul were also the secretaries of the cutting-edge art collective, The Berlin Secession, which was pushing modernism forward in the country.

It is not surprising that Julius would have snapped up the painting quickly from Pissarro’s Paris dealer, Durand-Ruel. Julius would have likely known that “Rue Saint-Honoré” was unique within Pissarro’s oeuvre, which was dominated by landscapes. When Julius died, his son Friedrich, an opera conductor, inherited the painting. After Friedrich died in 1926, the painting passed to his wife Lilly, Claude’s grandmother.

The Aryanization of German society, by which laws and regulations were placed on Jews by the Nazis starting in 1933, was a practice run for the art plundering operation that took place across the European continent in the 1940s. The forced sales and looting of Jewish property became a weapon of war, used to dispossess Jews first of their livelihood, then of their physical possessions, culminating in their murders in concentration camps.

Kunst und Künstler was shut down by the Nazis in 1933, and in 1936 all Jewish printing houses were delisted from the Reich Chamber of Culture, established by Joseph Goebbels. The successive actions rendered the family businesses untenable. Bruno fled to England and started a new publishing company. Claude meanwhile was a Holocaust survivor many times over. He and his father escaped to Prague, but he was soon sent to boarding school in England when Czechoslovakia became unsafe for Jews. In 1940 during a school trip to France, he was seized by Vichy collaborationists and sent to an internment camp in Morocco. He nearly died of typhoid fever before the camp was liberated in 1941. He was taken to Cleveland, where he started over as an immigrant refugee.

Meanwhile, Lilly had remarried and moved to Munich, staying in Germany longer than the rest of the Cassirer family. In 1939, she and her husband Otto applied to the Nazi government for a visa to leave Germany and take their possessions with them. A Munich-based art dealer, Jackob Scheidwimmer, was appointed by the Nazis as the official appraiser for their estate. Likely knowing of Hitler’s penchant for Pissarro, Scheidwimmer denied the request to take the painting out of Germany and demanded Lilly sell it to him for 900 Reichsmarks (approximately $360, or $7200 today), far below market value. Lilly knew that if she did not agree, her exit visa would be denied. The funds were deposited into her account, which was already blocked. Far greater in value would be the amount the couple would have to pay to leave the country — approximately $4 million today in both a Jewish asset tax and an escape tax.

Lilly and Otto fled to England. After Otto’s death in 1957 she moved to Cleveland to live with Claude. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Claude said that his grandmother never lost hope that the painting would be found, although she did not live to see it. She bequeathed the rights to the painting to him. By 2000, Claude had retired from a distinguished career as a photographer — he had even photographed John F. Kennedy and Paul Newman — when he got the fateful call from a former client who knew the family saga. She had seen the painting in a museum catalog.

Signature Drawing: The signature of Impressionist Camille Pissarro appears on “Landscape in the vicinity of Louveciennes (Autumn)”, a painting from 1870 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales November 18, 2005 in Sydney, Australia. By Getty Images

Claude first petitioned Spain to return it. When that failed, he sued Spain in California. To fund the legal efforts, the family enlisted the help of the United Jewish Federation of San Diego, which is a co-plaintiff in the case. Claude died in 2010, but his son and daughter David and Ava took up the mantle. Ava died in 2018.

The serpentine journey this painting would take after Lilly “sold” it under duress underlies the legal battle. After Scheidwimmer acquired the painting, he forced the Jewish art dealer Julius Sulzbacher to trade three German paintings for the Pissarro. Sulzbacher took the painting to Holland on his own escape but it was later seized by the Gestapo who took it back to Germany. It was next sold at a Nazi auction in Düsseldorf. In 1943, it was sold again in Berlin to an anonymous buyer for 95,000 Reichsmarks.

In 1951, the painting was smuggled from Germany to California and sold at the Frank Perls Gallery in Beverly Hills to the real estate mogul Sydney Brody. The next year, Brody asked New York City’s Knoedler Gallery to sell the work, which was purchased by Sydney Schoenberg from St. Louis. (The gallery is the subject of the documentary “Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art” and had been named in several lawsuits about Nazi-looted artworks).

In 1976, the painting made its way back to New York to the Stephen Hahn Gallery, where it was acquired by Swiss steel magnate Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza for $275,000. The Baron kept the painting at his estate in Switzerland until 1988 when the Kingdom of Spain leased his art collection for 10 years. In 1993, he sold his collection to Spain for $350 million.

The case has been the subject of nearly two decades of procedural wrangling, with three appeals to the Ninth Circuit. The main point at stake at the Supreme Court is “a relatively narrow issue,” says Stephen Zack, a lawyer at Boies Schiller Flexner who is representing the Cassirers. It comes down to how the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), the law that governs whether a foreign nation can be sued in U.S. courts, should be applied — a question known as “choice of law.” That is, were the lower courts correct to use Spain’s law of prescriptive acquisition to determine that the Baron (and thus the museum) had acquired good title to the painting? (Title in Spain is conferred to a good faith purchaser merely by holding onto property for seven years, three at the time in Switzerland). Or should California law, which states that thieves cannot pass on good title to anyone, including a good faith purchaser, apply?

The museum has downplayed the significance of this legal question, contending in its opposition brief that the divergence between the Ninth Circuit and the other appeals courts on this issue is not as considerable as claimed by the plaintiffs. In a statement, Nixon Peabody, the firm representing the museum assert, “At the conclusion of the case, regardless of which choice-of-law test is applied, the Foundation anticipates that its ownership of the painting — already recognized by the district court and the Ninth Circuit — will be affirmed.”

Zack, on the other hand, believes that the Supreme Court “will clarify the law that should have been applied is California law. And California law does not have a statute of limitations. Stolen property is still stolen no matter when it’s recovered and that gives a right to get it back. So public policy and the law and morality all end up in the same place.”

Nicholas O’Donnell, partner in the Art & Museum Law Practice at the firm Sullivan & Worcester concurs. For the Cassirers’ case, he filed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court on behalf of Mark B. Feldman, the former U.S. State Department legal adviser who was primarily responsible for drafting FSIA. Their position is clear: the application of Spanish law is a misinterpretation of FSIA and that California law should apply.

O’Donnell told me that applying federal common law “doesn’t really exist anywhere except the Ninth Circuit. All of the other federal appeals courts have held — no, you look at the choice of law rule in the forum state where the case is pending.” Furthermore, he states that the lower courts’ decisions are contrary to international principles governing looted art, including ones Spain is a signatory to, including the Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets and the UNESCO treaty on illicit transfer of cultural property. This could be relevant because, as O’Donnell says, “In a separation of powers context, it would be inappropriate for judges to be doing things that interfere with international policy.”

Even the United States government has taken an interest in the case. The Solicitor General will participate in the oral arguments Tuesday, taking the position that California law should prevail. The outcome of the case, the U.S. contends “has implications for the treatment of the United States in foreign courts and for its relations with other sovereigns.”

“Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I:” 1907 painting by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), oil, silver, and gold leaf on canvas. Neue Galerie New York. Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund. Courtesy of Neue Galerie New York. Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, and the Estée Lauder Fund, the heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer

For the public, it may be surprising to learn that cases involving looted Nazi art often do not reach the question of whether artwork can be returned or not. Steven Thomas, head of the art practice at the firm Irell & Manella LLP who represented Maria Altmann and the other Bloch-Bauer heirs in the sale of five Nazi-looted Gustav Klimt paintings (including “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer,” the “Woman in Gold”) told me that the large number of potential “procedural challenges can be devastating to a theft victim, especially where it might be clear that, yes, it was stolen — but you can’t bring a case here in the U.S. because your claim is barred, or if not barred, we rule foreign law applies and it favors the current possessor not the victim.”

“It has been a very long and sometimes torturous journey that should have been very simple,” said Zack, the lawyer for the Cassirers, “We would hope that at the end of the day, both for legal and moral reasons that this painting is returned as soon as possible to the Cassirers. In the meantime, there have been several generations who have been trying to do this, a number of whom have died waiting.” For the Cassirers, the opinion of the Supreme Court will determine whether a 20-year quest ends on a narrow legal issue, or whether the quest to get back their Pissarro painting will continue — in the courts.

Michelle Young is the founder of Untapped New York. She holds a degree in the History of Art and Architecture from Harvard University and a master’s degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, where she is an Adjunct Professor. She has written for The Guardian, Hyperallergic, Curbed, and Business Insider and her photography has been published in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, . She can be reached at @untappedmich.