He made 613 paintings of commandments and 915 collages of proverbs — but who’s got room to show them all?

Like RIchard Dreyfuss in ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind,’ Archie Rand feels compelled to create

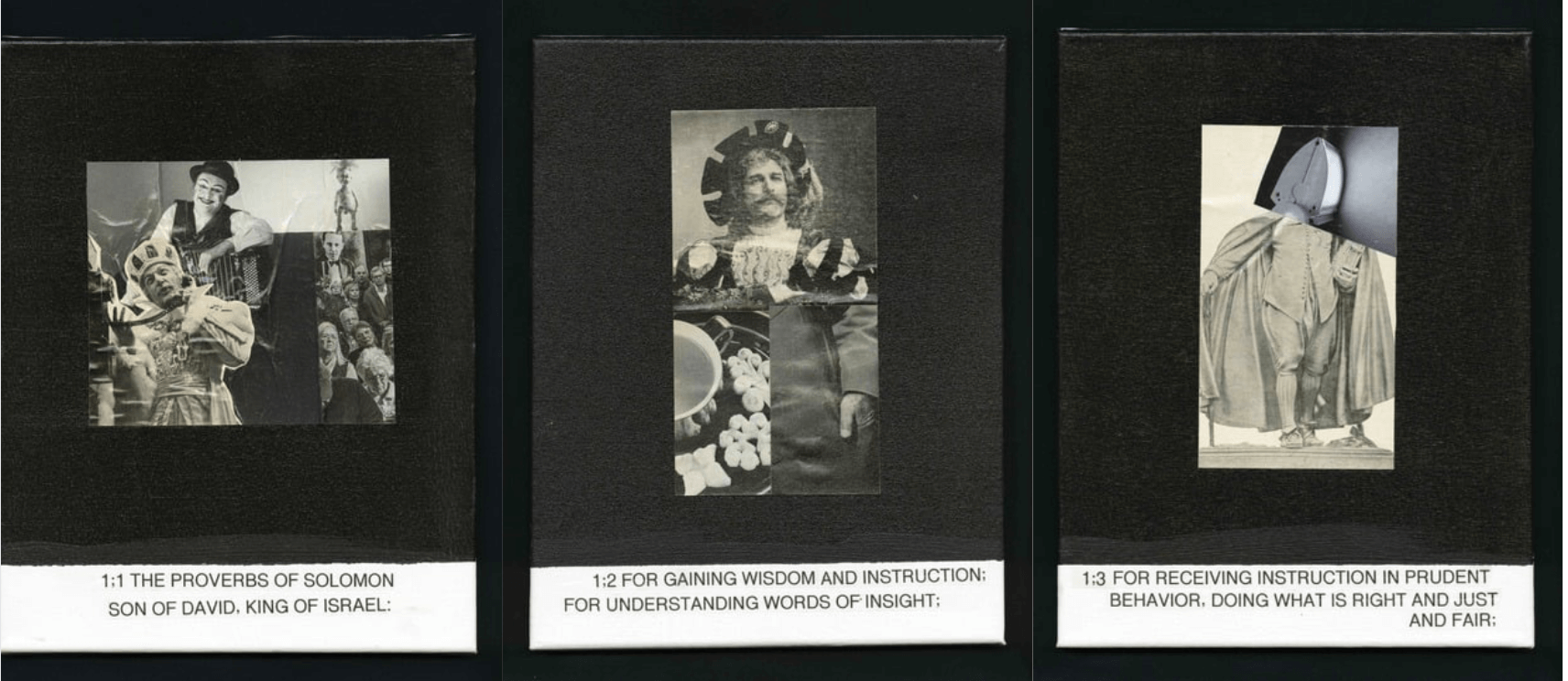

Archie Rand’s 915 collages represent each of the 31 verses of the Book of Proverbs. Courtesy of Archie Rand

When Brooklyn artist Archie Rand completed painting each of the 613 commandments in 2006, Rand was dubious that it would receive any critical acclaim, let alone be accorded museum exhibition space.

“To my happy shock, it became a huge success,” Rand said. “The book sold very well. In fact, it’s still in print. There are shows of it all the time and people come and read mitzvahs that never in their lifetime would they ever read.”

Now Rand has just completed 915 collages representing each of the 31 verses of the Book of Proverbs and, once again, he’s saying, “There is no audience for this.”

In fact, Rand called a company that installs steel shelving for supermarkets and had it build about 15 shelves in a wall of his studio so he can store the canvases.

“They are going to sit there until I die unless…” he told me. “The ‘613’ needed about 2,000 square feet of space to show and this needs a couple of hundred more feet. So even if somebody wants to show it, you need the Whitney Museum or something.”

The mostly black and white collages are not illustrations but rather images that are placed on a canvas. Below each is a verse of Proverbs.

Rand, 74, whose home and studio are in Clinton Hill, said the project, which took about a year, was something he was “propelled” to do.

He likened his experience to the scene in Close Encounters of the Third Kind in which the Richard Dreyfuss character felt compelled to pile dirt in his kitchen.

“I don’t want to get mystical or anything,” he said. “I’m not saying that God — the guy with the white beard, you know — pointed his finger and said, ‘Archie do this.’ I’m just saying it hasn’t been done; it needs to be done. Judaism needs an enormous amount of iconography to fill itself in. And even if I’m completely wrong, and if none of these images work, at least I’ve given it my effort. It’s like, you know, the job is not yours to complete, but you’re not free to withhold from working on it.”

Rand said he began the project by buying canvases, painting them black and then putting collages on them that consisted of newspapers as old as 1868 and magazines dating back to 1910 that he had bought since he was a kid at flea markets and that were given to him by people who were throwing them away.

“I just had boxes of this stuff,” he told me. “I finally said, either I throw all this stuff out or I use it. And then I said, ‘You know, if I put this pelican next to this jar of peanut butter, something happens.’ I don’t know what happens but it’s weird. Why does something happen? And what does that mean? Wait a second. Does that mean that you shouldn’t cheat your neighbor?”

In that way, he found that by putting two or three totally disparate images together, they somehow connected with a verse from Proverbs.

“They’re not haphazard — I didn’t just throw things together,” he said. “I kept reading and as I was putting these images together I kept thinking, ‘What type of poetic transference am I getting?’ And then I would read the sentence that inspired it and most closely linked up to it. And that became the pairing of the image and the text, which when read and viewed together would hopefully cause some kind of meditative or synaptic response from the reader and viewer.”

This is not something that can be explained rationally, Rand acknowledged, but “it is how art has worked since its inception. Art is not a rational pursuit per se, or, as Leonardo da Vinci said, it’s an acquisitive — it’s a thing of the mind.”

The success of this project, Rand said, is not that important. But “if there’s one image and one text that clicks with any one potential viewer even 50 years after I’m dead — God willing they should still be available digitally — then it will have served its purpose.”