The golden age for American Jews is over — and wow was it short

Considering the ’eminent’ lives of Leonard Bernstein, Mel Brooks, Betty Friedan and Norman Mailer, David Denby ponders the end of an era

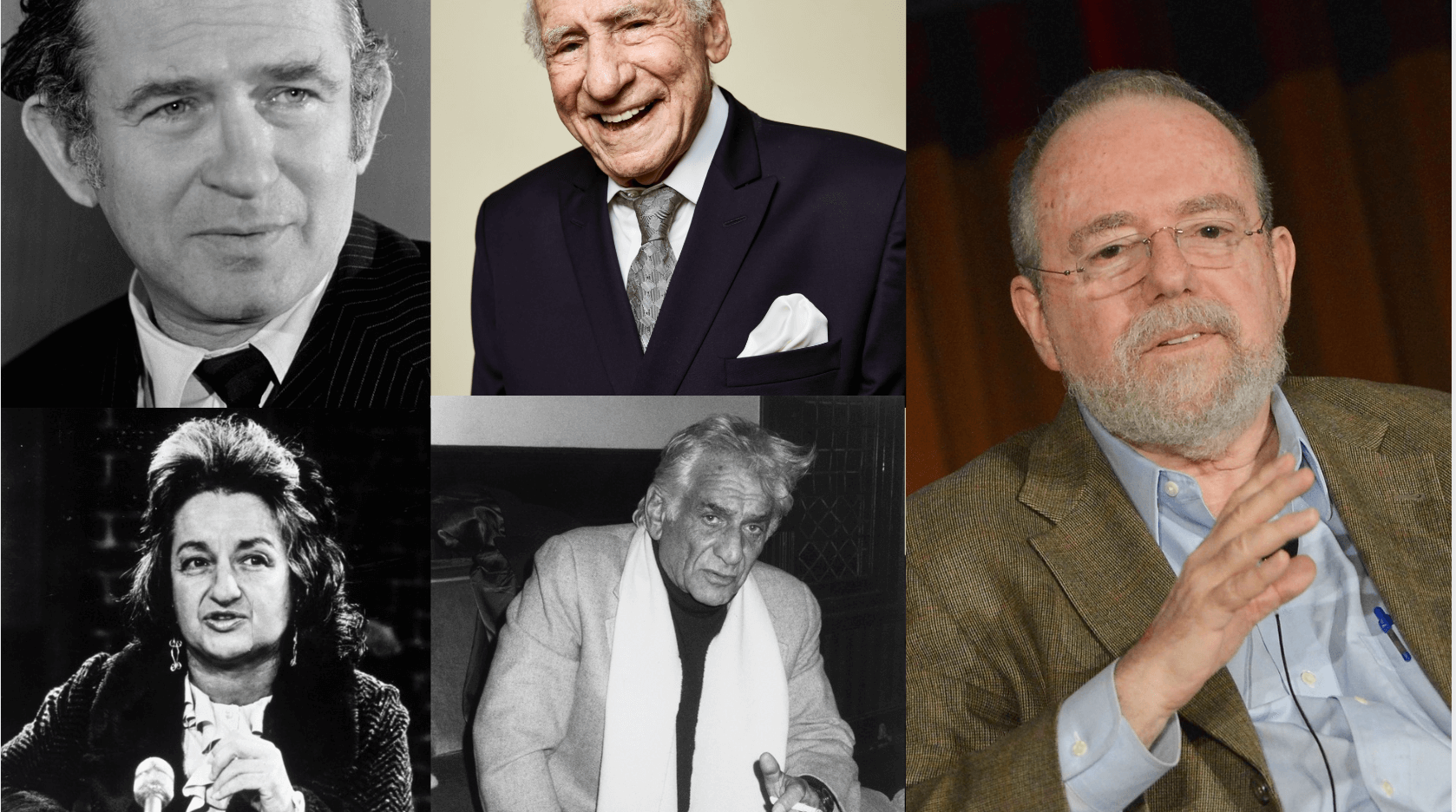

‘Eminent Jews,’ features biographies of Leonard Bernstein, Mel Brooks, Betty Friedan and Norman Mailer. Photo by Getty Images

Eminent Jews: Bernstein, Brooks, Friedan, Mailer

By David Denby

Henry Holt, 40o pages, $32

When Lytton Strachey wrote his Eminent Victorians in 1918, the Victorian period was clearly finished. Queen Victoria herself had died in 1901 and when one looked back at her reign from beyond World War I’s killing fields of Ypres and the Somme, the distinguishing features of the 19th century already felt like history. The four folks he wrote about were long dead. The era was gone.

It would be polemical to make the same claim about the subject of David Denby’s new book Eminent Jews and yet it is in keeping with the social and political tone of a book about four ostensibly cultural figures. Denby implies — by substituting “Jews” for “Victorians” — that there was a Jewish era and it has gone. And, though the chapters themselves only hint at this interpretation of history, the preface written later than the rest of the book looks back explicitly on a “‘Golden Era’ [of] relative safety and abundant achievement for the American Jews after the Second World War.”

As well as echoing Strachey’s book’s title, Denby cites him as a direct inspiration. Just like the book of a century earlier, Eminent Jews is a quadruple biography of culturally pivotal figures who embodied an age. Unlike Strachey’s Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold and Gen. Charles “Chinese” Gordon who lived decades apart, however, Denby’s subjects were all born within a much narrower period. Indeed, Leonard Bernstein was born three months after the publication of Strachey’s book, and the other three, Mel Brooks, Betty Friedan and Norman Mailer, were born within eight years of him.

Denby lists his subjects alphabetically in the book’s subtitle but he treats them in a different order, beginning with the indefatigable showman Brooks, moving onto the feminist Friedan (her husband’s family dropped the “m” because they thought that “Friedman” was too Jewish), before dealing with the bewildering literary paradox of Mailer (the “old, fat, bombastic lying little dynamo” as per one of his wives that Denby quotes) and then maestro Bernstein.

Throughout the book, Denby tries to add to biographies rather than to duplicate them. The book places explicitly Jewish lenses onto his four subjects and, to that end, Denby synthesizes their biographies in zippy fashion as well as adding his own analysis and sometimes even reporting. Though the book as a whole is quite large, each biography is quite compact and can be read as an entertaining and informative section on its own.

Brooks kicks off the book because he provides Denby with his most straightforward challenge and his most engaging subject. Since he is Jewish from his roots to his tips, the biography fits seamlessly into the premise of the book. Brooks’ manner, biography, and jokes are centrally, avowedly Jewish. His achievements — not least as an EGOT — are beyond any real question. His personal longevity is delightful, his professional longevity freakish, and they both give the author plenty to explain and describe. Denby can happily use Brooks to encompass an era that stretches from Sid Caesar to Judd Apatow via “Joan Rivers, Woody Allen, Jerry Seinfeld, Sarah Silverman, and just about every other Jewish comic you could name.”

Friedan feels like the least intuitive subject of the four for Denby since he is more of a cultural critic than a political reporter. He needed to include a Jew who changed not only “culture” but also “the culture” during a period of such social upheaval. Not only is it crucial for Denby to include someone responsible for such positive change, but, especially for such a sexist period of history, it’s important to have someone other than a short Ashkenazi man in the mix. Friedan, the socially awkward visionary who inspired second wave feminism, is a helpful inclusion because of her Jewish upbringing, her social impact and because, in later life, she often spoke to progressive Jewish audiences about her achievement as a Jewish one.

Perhaps because Mailer was a writer — and an uneven one at that — Denby finds him the most challenging. Perhaps because Mailer had a continuing obsession with violence, in others and in himself, it’s hard to justify glorifying him. Perhaps because he was simply not very Jewish, Mailer is the most difficult of the four to present as an eminent Jew.

What is Jewish about Mailer apart from his upbringing? His desperate avoidance of Jewishness in the characters that most resemble him? Denby has trouble answering these questions. Trying to give his characters a shared cultural context, Denby occasionally drops into oddly essentialized tropes of American Judaism. When, in a novel, Mailer tries and fails to lampoon a “WASP” idiom Denby both faults him and excuses him: How could Mailer have grasped something so alien to him? — “No Jew could have this kind of panache.” Still, that same culture produced Kirk Douglas — exactly a Jew with that kind of panache.

As a result of his astounding debut novel The Naked and the Dead and his propulsive promiscuity Mailer is an excellent subject. He had countless mistresses including long-term ones in Chicago and San Francisco, and six wives, one of whom he almost killed — stabbing her twice near the heart. But, though Denby explains clearly how he sees Mailer’s achievements, and though he’s clearly fascinating, it’s difficult to see why he is more eminent, more Jewish, or more representative of the era than Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, or Bob Dylan to name just three major literary award winners. In summing up “the failures while proclaiming the overall splendid success,” Denby again struggles to make Mailer’s mixed legacy part of the Golden Age: “Like other Jews, he was put on earth… to do serious thinking about many things.”

There is no such doubt as to how the author chose his fourth subject: Denby loves Bernstein. Despite the composer-conductor’s flawed personal life, Bernstein was a peculiarly gifted musician and one whose transcendent art Denby tells us “changed my life.” The chapter is a biography, yes, but it is also an extended attempt to address the feeling Denby had after listening to Bernstein conduct Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 in April 1962 —“That last movement opened gates of sensation and feeling that I had never experienced before, at least not outside of dreams.”

It’s Bernstein’s tremendous generosity of spirit, the need to give all that he has received, to teach, or perform, or direct, or all three at once, that marks him out for Denby. This constant attempt to connect, rather than impose, sets Bernstein apart from his great rival, the famous conductor, privileged member of the wealthy Austrian elite, and later member of the Nazi party, Herbert von Karajan.

The prologue and epilogue (At Home in America I and II) are both attempts to justify the Jewish lens on these four. They veer into the language of essentialism again: “As they liberated themselves, they became sages, secular rabbis without shawl and tefillin, exemplars of full-bodied, fearless life, unrespectable but still demanding the utmost of themselves and other people.” And they do not necessarily support his choice of characters — the foregoing description sounds like Dylan more than any of the four he chose. But, much to my surprise, they do work to sew the biographies onto a tapestry of late 20th century American history that was kind to Jews and kind to some eminent Jews.

The short horizon is at least partly because Denby — who was the longtime film critic as well as staff writer at the New Yorker — has chosen to write about the lives of iconic figures who were active while he was a professional writer. One of them, Brooks, is even still alive, aged 98, at the book’s publication. But the claustrophobic constriction and end of the Golden Age goes to illustrate how, despite the brightness with which Brooks, Bernstein, Mailer, Friedan, and others, shone, the Jewish American Golden Age was frighteningly short=lived.

For Denby, the lesson is that American Jews need to display assertive pride in the face of political tribulations. Rather than being idly representative of a generation, Mailer represents this forthrightness himself, and accentuates it in the other three. Though Denby could have chosen, say Louis Mayer as an example of an eminent Jew, he scorns the Hollywood moguls like Mayer who kept Jewish characters and any criticism of Germany out of the movies in the 1930s. That type of action now, he notes “would be a disastrous Jewish response to the present moment of danger.” And that’s why we need Mailer and his pugnacious attitude in the book and in our minds. In a comment intended as a communal exhortation, Denby quotes Mailer telling his sister, Barbara, “Act stronger than you feel, and you will soon feel as strong as you act.”