How Dean Stockwell fought antisemitism and inspired Jewish moviegoers

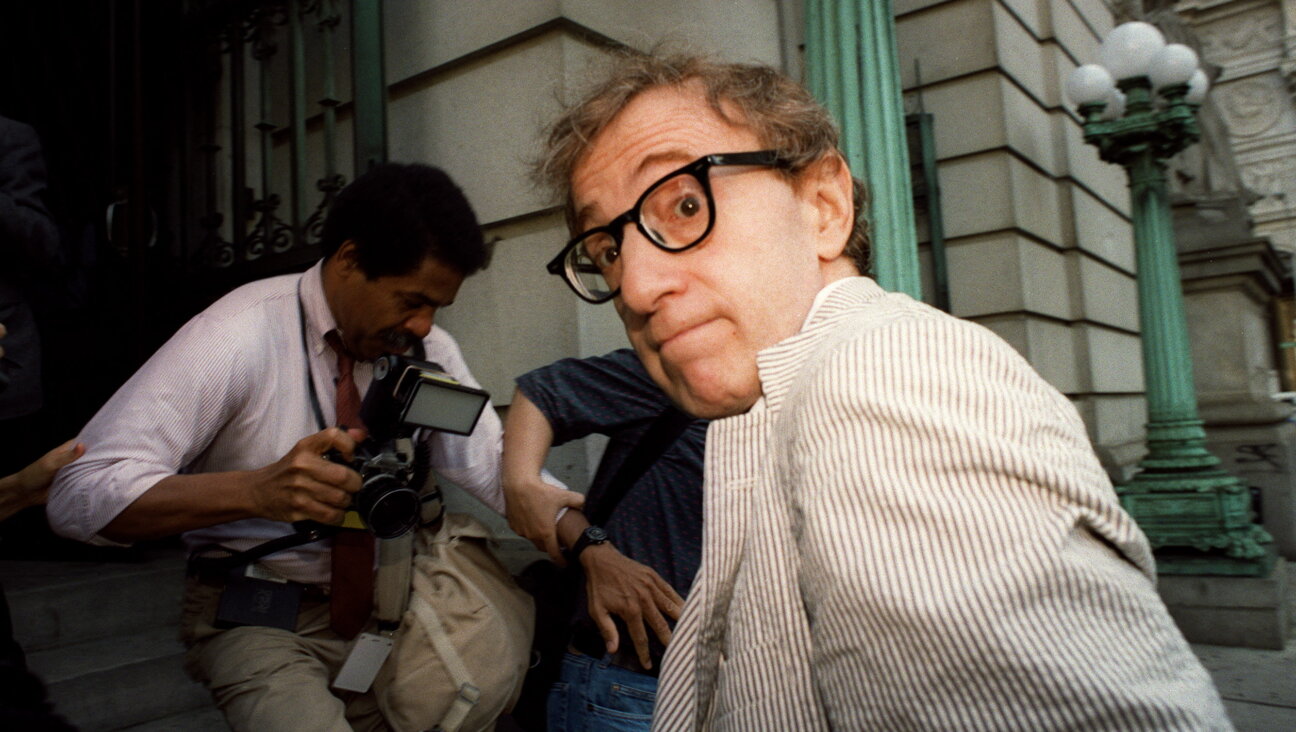

Dean Stockwell By Getty Images

Dean Stockwell, the Hollywood actor who died on Nov. 7 at age 85, is best remembered for appearances in such films as “Dune,” “Blue Velvet,” and “Married to the Mob,” in addition to the TV series “Quantum Leap” and “Battlestar Galactica.”

Yet starting as a child actor at the beginning of his lengthy career, Stockwell also incarnated onscreen some captivating roles with Jewish resonances. In the 1947 movie adaptation of “Gentleman’s Agreement” the novel by Laura Z. Hobson, Stockwell was already a vividly emotional performer.

Indeed, Stockwell’s scenes as the son of a reporter who feigns being Jewish to experience antisemitism in postwar America, hit home in a way that the otherwise stiff, wooden, and repressed adult actors do not achieve. Stockwell’s screen father was played by Gregory Peck, hampered by a limited histrionic range which the American Jewish film critic Manny Farber likened to that of “an ironing board.”

By contrast, Stockwell’s account of schoolyard taunts from classmates who suddenly think he is Jewish is heartrending. The boy’s innocent questions in the screenplay by Moss Hart, one of the few real-life Jews associated with the film, evokes the basic mystery of prejudice:

“They were playing hop, and I asked if I could play too, and the one from school said no dirty little Jew could play with them. And they all yelled those other things. I started to speak, and they all yelled that my father has a long curly beard, and they turned and ran. Why did they, Pop? Why?”

Gregory Peck’s only solace is to proffer a glass of water. Later in the film, as the school attacks escalate, Stockwell cries to his father: “They called me a dirty Jew and a stinking kike, and they all ran away.” As the target of the most violently expressed antisemitism in the drama, which otherwise is limited the level of impolite murmurs at restricted country clubs, Stockwell is singularly impassioned, communicating the theme poignantly.

Soon after “Gentleman’s Agreement,” Stockwell made another film which struck a chord with Jewish audiences. “The Boy with Green Hair” (1948) a fantasy by the Jewish screenwriters Ben Barzman and Alfred Lewis Levitt, was about a young war orphan, played by Stockwell, who is taunted after his hair mysteriously turns green.

The soundtrack includes a hit song, “Nature Boy” by George Alexander Aberle, a tunesmith of Jewish origin known as eden ahbez.

In a memoir, the conservative gadfly David Horowitz noted that as a child, “The Boy with Green Hair” was his favorite movie because of its message that “surface differences don’t matter, except to the ignorant.”

The Austrian Jewish beat poet Ruth Weiss went even farther in her admiration of the film, dyeing her own hair green “in solidarity with Stockwell’s character, as a symbol of peace.”

Indeed, the filmmakers intended the story as a pacifist allegory and reminder of the damage caused to children by war. Yet Jewish viewers clearly felt a special identification with Stockwell as protagonist beyond the ostensible subject matter.

Film historian N. Megan Kelley alludes to a review in “Ebony Magazine,” the African American publication, differentiating “The Boy with Green Hair” from “Gentleman’s Agreement” and “Crossfire” (1947), another film about the dangers of anti-Semitism, with the latter two classified as examples of cinematic art that “blasted religious prejudice.”

Even “The Happy Years” (1950), another Stockwell film, somehow inspired the authors of “The Educators’ Field Guide to the Torah Aura Productions Hebrew/Prayer Program”

Stockwell played a non-Jewish cheating schoolboy whose elaborately prepared cheat system allows him to eventually master a difficult academic subject. This example suggested to pedagogues of Torah Aura Productions, a Jewish educational publishing company based in Los Angeles, that Hebrew students could likewise be taught “to recognize patterns and approximate translations without their ever fully mastering the language.”

As the years passed and Stockwell confronted typical challenges for child actors who age out of habitual roles, he was cast in less sympathetic roles. One such, Judd Steiner, was a fictionalized version of the murderer Nathan Leopold half of the notorious homicidal duo Leopold and Loeb.

The American Jewish writer Meyer Levin wrote a novel, “Compulsion,” based on the 1920s case, adapting it in 1957 for Broadway. There Stockwell starred as Judd Steiner with trademark boiling intensity which became part of his performance repertory; in later life, even an anodyne interview about his film career could take eerie turns, with Stockwell suddenly behaving like a serial killer who refuses to admit where the bodies are buried.

Stockwell also played Steiner in the Jewish director Richard Fleischer’s 1959 Hollywood adaptation of “Compulsion.” Meyer Levin, who also authored several novels celebrating Yiddishkeit, such as “Yehuda” (1931) set on a kibbutz in Palestine, and “The Old Bunch” (1937) about Jewish immigrants in Chicago, could not be suspected of anti-Semitism because he chose to focus on the story of Leopold and Loeb.

Yet the Motion Picture Project (MPP), founded by the National Jewish Community Relations Council, expressed concern that the film’s characters still had Jewish-sounding names, even if the film was cast with non-Jewish actors. Patricia Erens’ “The Jew in American Cinema” notes that in the final result, Stockwell and other characters were “completely de-Judaized.”

Even so, by this time, Stockwell’s repeated appearances in movies with homilies against racism, and specifically antisemitism, may have possibly misled the literary historian Philip Beidler. In a study of America after World War II, Beidler wrote that Dean Stockwell was a cast member in the screen version of “The Diary of Anne Frank” (1959)

In fact, Stockwell did not appear in that film, although he did have a short-lived marriage with its breakthrough starlet, Millie Perkins, who played the eponymous heroine.

Even had he been asked, it seems unlikely that Stockwell would have participated in the filming of “The Diary of Anne Frank,” since his longtime artistic colleague Meyer Levin had sued the authors of the edulcorated stage and screen versions for having suppressed his own dramatized version of Anne Frank’s story, created with the approval of her father Otto Frank.

For a time in the 1960s, Stockwell dropped out of the entertainment industry, preoccupied with consuming alcohol and recreational drugs. It was perhaps a spell of belated childishness that he had not been permitted to express during earlier years on film sets. Stockwell retained ties to Judaism, as the analyst of esoteric mysticism Erik Davis explains, through lessons in a West Coast variation on Kabbalah by the American Jewish collage artist Wallace Berman.

And during a further career dry spell when he was reduced to appearing in dinner theater, Stockwell accepted a role that had been rejected by Gene Wilder in the cheapie horror comedy “The Werewolf of Washington” (1973). This satire of the Nixon administration, written and directed by Bronx-born Milton Moses Ginsberg. was like an extended Jewish joke, and an occasion for Stockwell to show his talent for levity.

Usually, from the time of “Gentleman’s Agreement” onward, he was valued for his convincing onscreen tears. Throughout the intermittent tsouris of his career that lasted for over seventy years, Stockwell’s tragic moments inspired the empathy of generations of Jewish filmgoers.