Carol Kane, Robert Smigel and Nathan Silver on how ‘Between the Temples’ is an ode to Jewish questioning and lifelong learning

The new comedy is about a cantor and his adult bat mitzvah student

Jason Schwartzman, teaching a group of young Jews about what it means to love one’s neighbor in Between the Temples. Photo by Sean Price Williams.Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

When director Nathan Silver was shooting a documentary about his muse — his mom, Cindy — he brought his crew to film her at her temple in Kingston, New York. There, he learned something new about her that raised more than a few questions.

“I found out she was in this b’nai mitzvah class. And I was like, ‘What? You’re gonna get a bat mitzvah?’” said Silver, who along with actors Carol Kane and Jason Schwartzman, was giving press interviews at a publicity office in Manhattan. The filmmaker, behind such indie hits as Thirst Street and The Great Pretender, was appropriately clad in a “My mother is a travel agent for guilt trips” T-shirt under a patterned button-down.

Cindy Silver didn’t end up going through with the rite of passage, but her preparations, with some goading from a publicist friend, gave her son the idea of a Harold and Maude love story between an adult bat mitzvah student and a young faith leader at a synagogue. The result is Between the Temples, where a cantor who lost his voice finds it with the help of an older-than-average pupil.

The role of Benjamin Gottlieb, a recent widower and cantor for a Reform shul upstate, was written for Schwartzman. Kane, the Oscar nominee known for her roles in Hester Street, Taxi and The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt was later cast as his adult student, a widow named Carla O’Connor, one half of the May-December (Av-Adar?) romance. Kane came in with her own idea for the character, inspired by her mother: making her character Ben’s old elementary school music teacher.

“My mama is a composer, musician, 97 now, at the piano every day,” said Kane. Her mother, Joy, moved to Paris at 55 to become a music teacher, reinventing herself. “It’s very parallel to Carla’s story of just thinking, ‘I gotta start over. I got to give myself a new life.’ And Ben facilitates.”

Between the Temples, which opens Aug. 23, following a celebrated run at Sundance and the Tribeca Film Festival, was a learning experience for Silver and Kane, who were both raised secular. The film is brimming with Hebrew song, temple politics, Kabbalat Shabbats and jokes that may go over a goyishe kopf. Much of it was filmed on location at Silvers’ parents’ temple with extras pulled from the congregation.

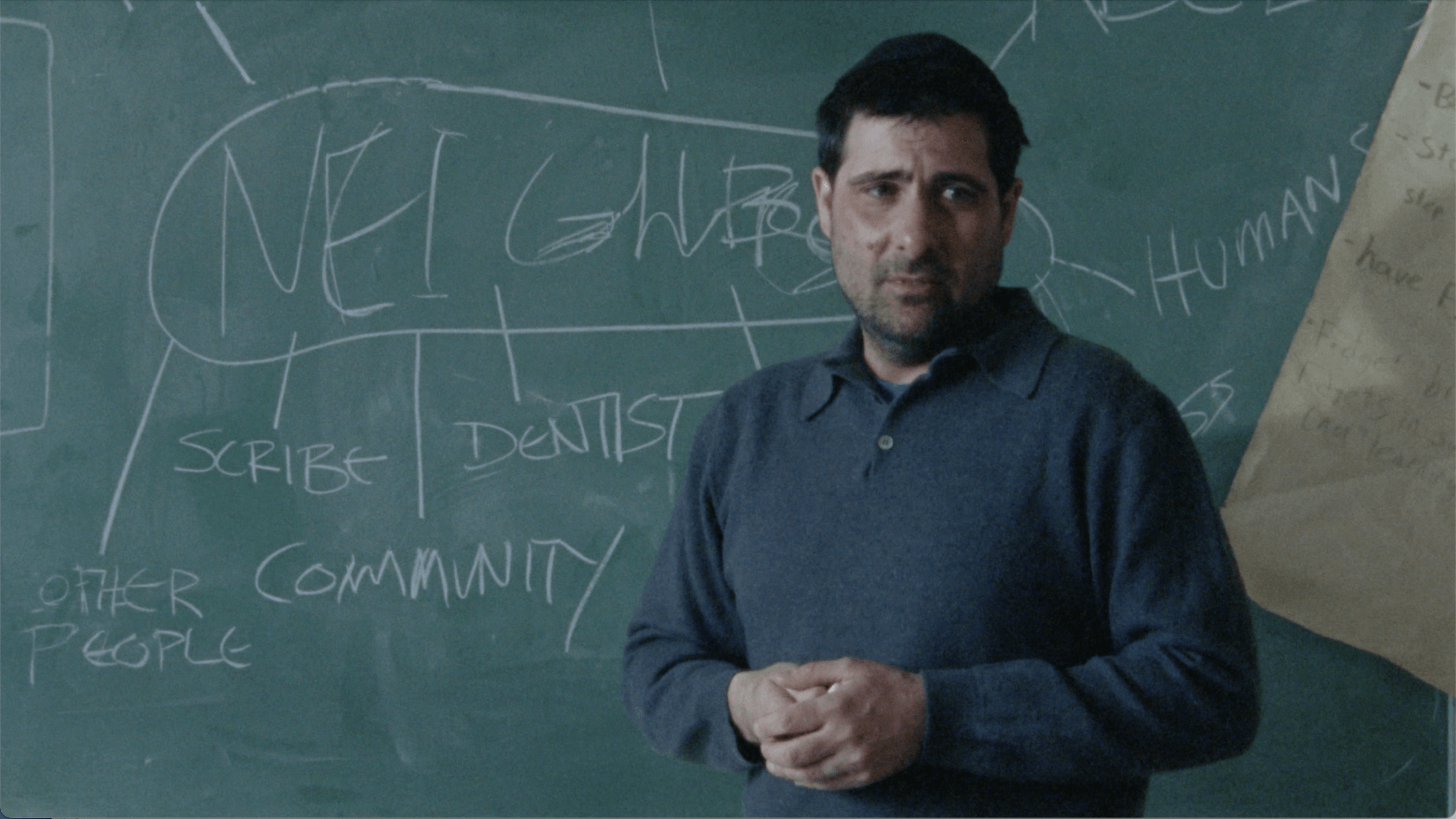

“The movie is about community,” Schwartzman, who taught himself traditional songs like Yedid Nefesh to play Ben, said at a Tribeca Film Festival Q&A. Community was more than just a theme, Schwartzman said; it was “the set that Nathan made for us,” one where collaboration and questions were strongly encouraged.

This shofar is fine for putting

When Silver, and his non-Jewish co-writer, C. Mason Wells, had questions during production, they appealed to experts: Rabbi Mikey Hess Weber of Columbia Jewish Congregation in Columbia, Maryland; Robert Smigel, who plays Ben’s boss, Rabbi Bruce; and production supervisor Jesse Miller, who, when not working as a freelance film producer, is a b’nai mitzvah tutor.

“This was just kind of a random, lucky fluke that it kind of joined these two parts of myself in a way that I would never have predicted,” said Miller, who isn’t branding himself as a Jewish consultant — at least not quite yet. It was Miller’s first time working so extensively with actors.

Miller and Smigel both went to day school as kids. Smigel, a legendary comedy writer and the hand that operates Triumph the Insult Comic Dog, attends Shomrei Torah, a Modern Orthodox shul in Fair Lawn, New Jersey. Together they advised on matters relating to temple life, like keeping the Torah Ark closed and suggesting a fitting Torah portion for Carla (Kedoshim).

“To see a movie that’s comedic about religion, but at the same time reaffirming the beauty of it, is so special,” said Smigel, who plays what he describes as a “somewhat mercenary version of a clergyman” with TKUNOLM vanity plates and principles easily bent by the promise of donations. In an early scene, Rabbi Bruce is shown putting a golf ball into a shofar.

“If you’re at all religious, you know that a shofar is sacred,” Smigel said. So as not to offend, he ad-libbed a line that this shofar wasn’t kosher. It gets a laugh every time.

About that Shabbat scene

The almost-15-minute Shabbat scene toward the end of the film was especially tough to get right, Miller said, given the varied ways Jews welcome the Sabbath. It had to be specific enough to be believable, but universal enough to pass a Jew’s BS detector. The cast, including Dolly De Leon and Caroline Aaron as Ben’s moms, shot the cacophonous, claustrophobic sequence with two cameras over two nights, a different version each time.

“It’s all about embracing the rituals and embracing the tradition and looking at it,” said Silver. “It’s like anything else in life: the absurdity of what we do. Like for instance, why do we eat at a table?”

Kane, at the table with Silver, interjected, “Who says we eat at a table?”

“Some of us do! I don’t often, I guess,” Silver conceded — but still questioned the custom. The interviewer half expected someone to ask why we recline on this night but not all other nights.

Silver, who cites Joan Micklin Silver (no relation) and Albert Brooks as inspirations, said that making this film has changed the way he approaches his Jewishness. In the spring, he attended his first Seder in years.

Kane, who sometimes had her mom in the room while she learned her Torah portion for the film, said the experience made her wish she’d been raised with more Jewish tradition, so she could make the choice whether or not to carry it with her.

She said she feels privileged to have a career where she can learn for roles — whether it’s Yiddish for Hester Street or an ancient Hebrew melody for Between the Temples. (In the interview, she asked what “cringe” meant when referring to a style of movies and TV, and took a note of it.)

Part of Judaism, it seems, is not being afraid to ask.

“I was somehow taught, but I don’t know by who — just the zeitgeist, maybe — it’s not a good thing to ask, because that means you’re ignorant,” Kane said. “Whereas this tradition is the absolute opposite: It means you’re a lifelong learner.”