In ‘Black and Jewish America,’ Henry Louis Gates Jr explores the history of Black-Jewish partnership and conflict

A new PBS series on Black and Jewish relations shows the promise and peril of allyship

In the first episode of Black and Jewish America, Henry Louis Gates Jr. (third from left) sits down at a Seder table with Black, Jewish, and Black-Jewish scholars and community leaders. Courtesy of McGee Media

The new PBS series Black and Jewish America: An Interwoven History is not the first piece of media to investigate the relationship between the two communities. But what’s unique about the program, narrated by scholar and Finding Your Roots host Henry Louis Gates Jr., is that it doesn’t shy away from the historic complexities of this partnership — and the many times it almost fell apart.

Alarmed by the recent rise in white supremacist hate crimes, Gates reconnected with Phil Bertelsen and Sara Wolitzky, who had worked on some of his past projects and are co-directors and co-producers of the series.

“I think we all felt collectively the same kind of revulsion at this rise of white supremacist hate,” Bertelsen, who was a producer on Gates’ Peabody Award-winning series The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, told me over Zoom. “The hoods came off, you know, and so we all, as storytellers and historians, grew concerned, and found this to be a great opportunity to kind of show the importance of shared experience and coalition building.”

Narrated by Gates, the four hour-long episodes recount chronologically Black and Jewish history in America from 1492 through the present using archival footage and interviews with historians and cultural scholars, such as Cornel West and Derek Penslar. From the first episode, they establish that the two identities have never been mutually exclusive. Gates sits around a seder table with white Jews, including author Abigail Pogrebin, and Black Jews, such as chef Micahel Twitty and Shais Rison, the African-American Orthodox Jewish writer known as Ma Nishtana.

By describing times when Black and Jewish people were allies as well as when they were in conflict with one another, the series feels more authentic — and more convincing — than other media about allyship that are often rooted in platitudes and a romanticization of the past. It’s impossible to have honest partnership without confronting uncomfortable truths: There were Jewish slave owners, there were members of the Black Power movement who subscribed to virulent antisemitism, and not all Jews were allies with the Civil Rights movement.

Wolitzky told me that Susanna Heschel, daughter of Rabbi Abraham Heschel, who famously marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma in 1965, recounted a department store called Tepper’s that was near the march. It was owned by Jewish businessman Sol Tepper who was a member of the supremacist organization the White Citizens Council.

“These communities are not monoliths in any shape or form, and at every moment you have differences of opinion,” Wolitzky said

Because many Jews were seen as white, they had legal and economic advantages that weren’t afforded to their Black neighbors, even while they faced social discrimination, such as university quotas and country club bans. Some Jews used this privilege to help Black people, and others used it to take advantage, such as Louis Armstrong’s manager Joe Glaser, who, according to jazz artist Ben Sidran, was likely not giving Armstrong his fair share of money.

The Jewish manager-Black artist dynamic has caused conflict throughout music history, in rock, rap, and hip-hop, although these other incidents aren’t mentioned directly in the series. Given the depth of the history of Black and Jewish relations, some stories and details had to be left on the cutting room floor.

“One of the things we couldn’t afford to do is tell the same story twice, even if it featured different characters,” Bertelsen said. “We were very eager to kind of look at Def Jam Records, and Rick Rubin, and Russell Simmons, and that crew. But we had told it in Episode #2, in essence, through Louis Armstrong and Joe Glazer.”

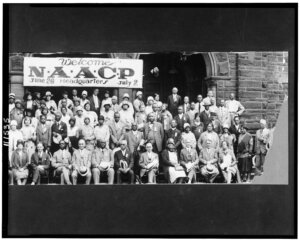

The creators have packed a lot into a relatively short amount of time, including both well-known incidents of Black and Jewish allyship — such as Jews co-founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — and stories that aren’t as broadly discussed — such as Black-Jewish partnership in Merriam, Kansas, to advocate for better Black educational facilities in the 1940s.

Black and Jewish ends by touching on the political fallout after Oct. 7, but offering hope in the form of an intercultural student dialogue group at UCLA founded in the wake of campus protests and led by professor David Myers, an occasional Forward contributor.

Of course, the story isn’t over. Since filming ended in 2025, new developments in national politics and concerning Israel have already popped up. The show mentions the Anti-Defamation’s League role in combatting Black labor exploitation in the Bronx, even as the organization has recently stepped back from broader civil rights causes.

Wolitzky mentioned the recent accusations of antisemitism in DEI initiatives as another issue that’s relevant to the ongoing story of how Black and Jewish people relate in America. However, like the changing ADL, it’s a story that we are still living through.

“These films are really a historical lens, and it’s always really hard to have that same sense of perspective on the current moment,” Wolitzky said.

The first episode of Black and Jewish America: An Interwoven History premieres on PBS on Tuesday, February 3rd at 9pm EST. On Feb. 5, Henry Louis Gates Jr., the filmmakers, and Sen. Corey Booker will discuss the series at 92NY.

Correction: The original version of this article misstated the name of one of the co-directors. His name is Phil Bertelsen, not Paul Bertelsen.