In 1943, an opera was composed at a concentration camp. Now, it’s a graphic novel

‘Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis’ adapts a German parable of life, death and despotism

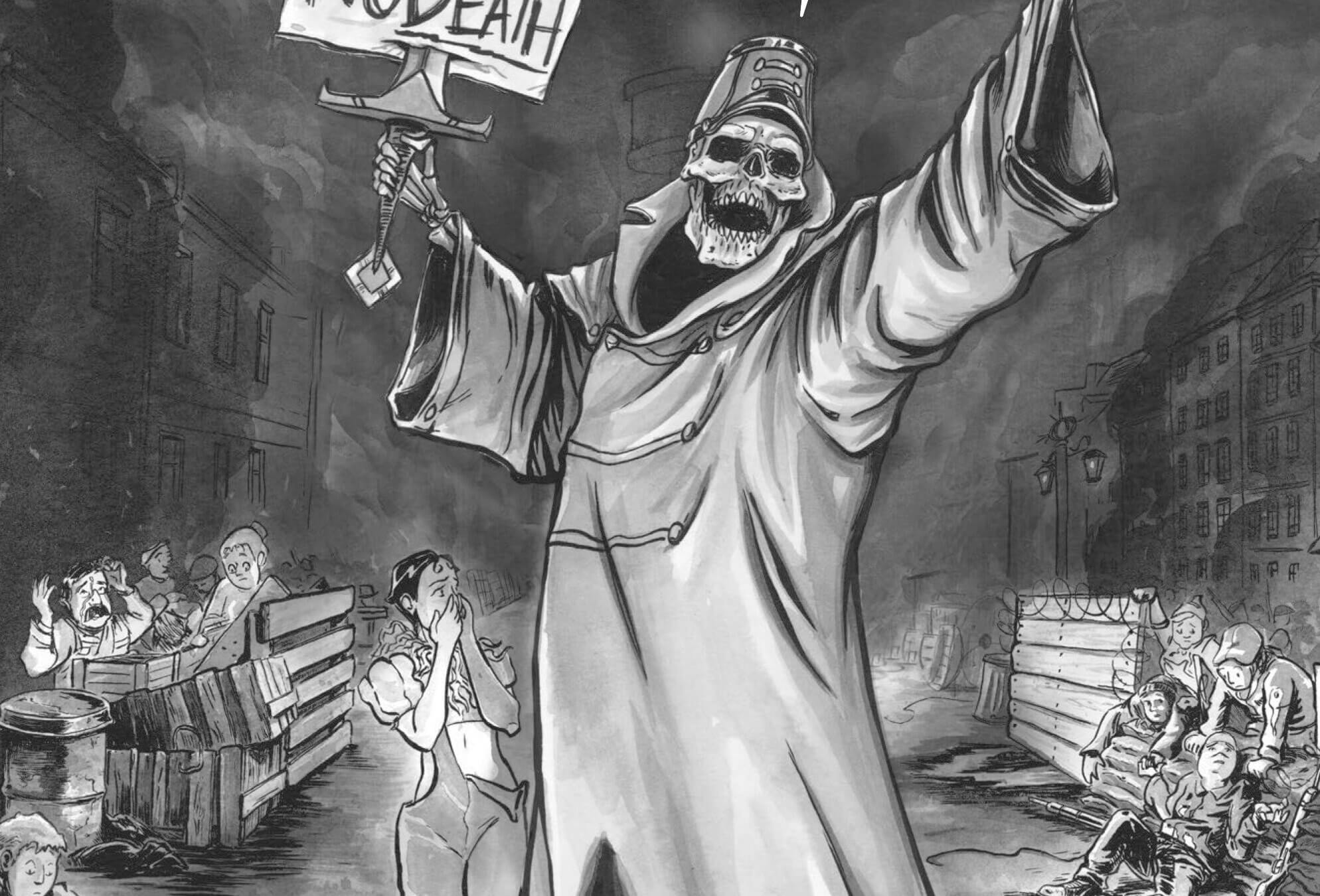

Death, tired of war and bloodshed, goes on strike. Image by Patrick Lay

Peter Kien and Viktor Ullmann’s opera The Emperor of Atlantis is an allegorical meditation on life and death — they wrote and rehearsed it in an atmosphere teeming with both.

The duo met in Terezin, the so-called “model concentration camp” outside of Prague, where prisoners, mostly Czech Jews, were encouraged to pursue creative endeavors before their deportation to ghettos and death camps. In 1943 they assembled the opera, with a libretto by Kien, a writer and illustrator in his 20s, and music by Ullmann, a composer and conductor in his 40s.

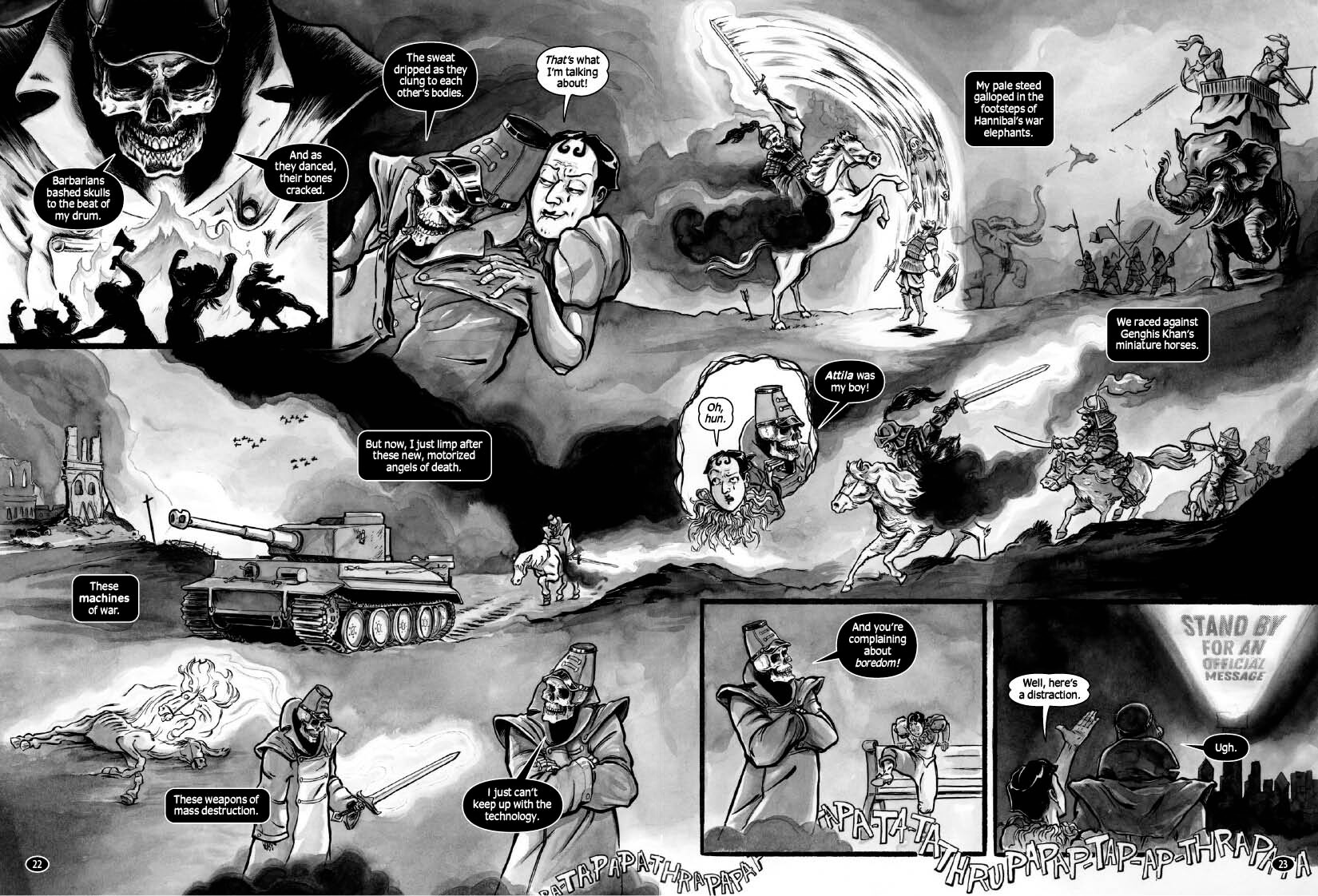

Its plot concerns the embodiment of Death, who, objecting to an order of all-out, mechanized war from a paranoid, reclusive dictator named Emperor Overall, goes on strike, sowing confusion and chaos because no one is able to die.

The opera was never performed at Terezin; Ullmann and Kien were deported on Oct. 16, 1944. Ullmann was murdered in the gas chamber at Auschwitz two days later. Kien died at the camp in late October, likely of typhus.

Remarkably, The Emperor of Atlantis did not disappear. Much of the sheet music and libretto survived, and in the 1970s musicians began staging it — with unsanctioned additions, some of which were supposedly suggested by Ullmann’s ghost via a spiritual medium. While relatively obscure, the piece has been performed at the Dutch National Opera, the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the Warsaw Chamber Orchestra.

In the late 1990s, Dave Maass, a teenager in Phoenix, Arizona, was browsing at a Best Buy when he found a collection called The Music Survives!, devoted to the “degenerate” music the Nazis tried to suppress. On the record — accompanied by a VHS tape — was a small selection from Kien and Ullmann’s opera. Maass was intrigued, and sought out a version of the whole show.

“It kind of became something that really changed who I am and made me think about the rights of prisoners, the importance of freedom of expression, about war and authoritarianism,” Maass, who researches and writes about surveillance technology for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said over Zoom.

After 9/11, the Patriot Act and wars in the Middle East, Maass realized that the opera wasn’t necessarily about Hitler or the Holocaust, but a work that “was designed to resonate over history.”

For years after discovering the opera, Maass was convinced that it should be adapted into a graphic novel.

“Peter Kien the librettist wasn’t just a librettist. He wasn’t just a poet. He was a prolific artist and illustrator,” Maass said. “Had he survived, he could have very well come to the U.S. and found a career in comics, because he really was a master of both text and illustration.”

When Maass met comic illustrator Patrick Lay in 2018, during a comics and robotics convention in Juneau, Alaska, he pitched him the idea.

“It’s this incredible sci-fi fantasy story,” said Lay. “But then it has this incredible backstory, right? It was written in a concentration camp in 1943, and so there’s immediately an additional level of political commentary of historical interest.”

Lay auditioned with a simple page, and now Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis is out from Dark Horse comics, complete with back matter featuring historical context and essays. For the art, Lay used an ink wash style, working off character designs by artist Ezra Rose.

Putting the book together involved deep research to try and find as close to a definitive version of the opera as possible. Maass visited Basel, Switzerland, where Ullmann’s handwritten score is kept in the Paul Sacher Stiftung, and the Wiener Holocaust Library in London, where there’s a handwritten libretto. He discovered that the most-produced versions of the opera strayed from the original or had plot holes that needed fixing.

Maass wrote a fuller story for the soldier, with the character design modeled off of sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld and, using poems and stories by Kien, created a backstory for the enigmatic tyrant Emperor Overall.

Maass and Lay both went to Terezin to observe the grounds, and the city of Atlantis is drawn to evoke its star-shaped layout. Visual motifs unique to the Czech Republic appear throughout the pages, along with allusions to David Bowie, partisan and photographer Faye Schulman and even Rep. Steve King’s infamous photo op with a toilet at an immigrant detention facility.

“We really wanted to embrace how the authors used irreverence and humor as a weapon of resistance,” said Maass. “It always makes me super happy when I see somebody reading it, family member or whatever, and I hear them chuckle.”

Maass and Lay are thrilled that people are discovering the original work through their text, which, they note, takes about as long to read as the opera (which can be found on YouTube.)

Maass and Lay were also keen to hammer home the undercurrent of censorship now being faced by books like theirs — that include queer characters and challenge autocracy — in school libraries across the country. Bans have targeted Art Spiegelman’s Maus and a graphic novel adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank.

In this context, Lay remembers the words of Viktor Ullmann as a source of strength.

“He’s got a quote about making sure that everyone knows they didn’t cry and weep at the banks of Babylon, but they persisted and they made art,” Lay said. “That was something that was really important for us to hold onto.”