A Transylvanian-American klezmer blues bash right at home at a Brooklyn fiddle summit

The Neighborhood Fiddle Summit brought together a melting pot of musical influences

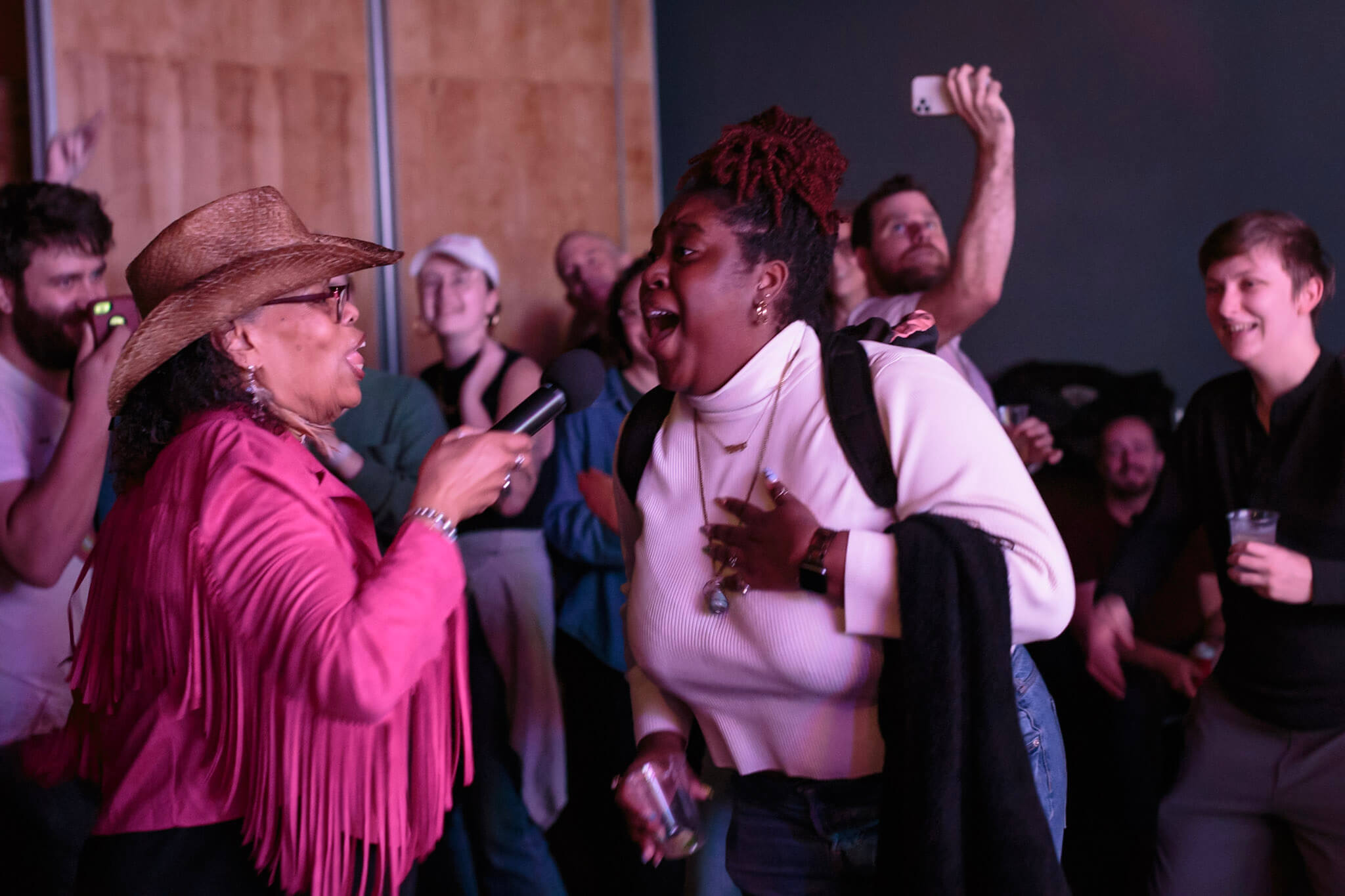

Henrique Prince, Zoë Aqua and Ira Temple at the Neighborhood Fiddle Summit. Photo by Jesi Kelley

Choosing the Neighborhood Fiddle Summit over Bad Bunny for a rainy night in Brooklyn reminded me that I’m team pajama, team apple pie, team rock ‘n’ roll. I love the merge, meld and mix of cultures, as people talk to people, generation after generation, learning how they do stuff and adopting the things they love. Often the crazy, foreign, new becomes the new norm, whether choosing comfortable sleeping wear from the Indian subcontinent; eating Turkish apples refracted through Germanic pastries and brought to America; or dancing to African rhythms played by post-Appalachian hillbillies.

While El Conejo Malo was being supported by Feid and Young Miko at the Barclays Center, barely half a mile away at Littlefield, two quite different acts convened. Klezmer violinist Zoë Aqua and old-time string band The Ebony Hillbillies came together for this “fiddle summit” hosted by The Neighborhood: An Urban Center for Jewish Life. Talking to the musicians and to the Neighborhood’s Rebecca Guber, the impetus for the event came mostly from Jewish studies scholar and musician Jeremiah Lockwood, whose Transylvanian genealogy and blues roots linked him to both the Romanian/klezmer folk stylings of the former and the old-time urban American string hoedown of the latter.

First came Aqua, fresh from a tour of the West Coast. She played — as part of a trio of fiddle, bass (Zoe Guigueno) and accordion (Ira Temple) — some of the tunes she learned and composed in Transylvania during the two years she spent there on Fulbright research grants. Aqua is only a couple of years older than Bad Bunny, but onstage she was channeling a more reserved persona: more great-aunt than rockstar. Though klezmer is often danceable, and though the crowd got into the music and set up some group dancing, the short set was more cerebral than foot-stomping.

Aqua is an educator and, while perhaps this early-weekend concert was not the time to fully elucidate the intersections between European folk musics, I would have loved to hear more of the connections. Especially as she was in a quiet, intimate mood in a concert bar venue where only 100 deeply engaged fans filled a space that could easily, and beneficially, have held twice that number, she could have gone further. Perhaps she could, for example, have explained how the work we were listening to embodied the musical conversations between “klezmer, Transylvanian music, Hasidic music, lautarească and more” that appear on her album “In Vald Arayn” (Into the Forest).

For example, after an arresting reflective tune inspired by a stream in the Central European hills, she played a song taught to her by Romanian folk musician Ioan Hârleț, aka “Nucu.” Nucu’s an 80-year old violinist from the village of Budești, none of whose family have taken on and learned his instrumental talents. Putting herself squarely in musical filiation, Aqua learned some traditional tunes and musical folkways of his particular, and peculiar, tradition and brought those to Brooklyn.

Jews were in Transylvania for about 500 years before the Nazis and their Romanian allies slaughtered them as aliens, so Nucu, who was born in 1944, knows lots of their musical influence but almost no Jews. Only through constructive cultural appropriation, like Nucu’s music, do the Jews survive in the region north east of Cluj. But they survive elsewhere in the country and Aqua is about to head back to Europe for a tour of four historic synagogues in Romania.

Then, as The Ebony Hillbillies mounted the stage — straight “from the concrete hills of New York City” — the volume, the tempo, and the overt sensuality went way up. In this iteration, the Hillbillies were a six-piece with Lockwood sitting in on banjo and guitar.

Unlike the gentle wedding band vibe of the Zoë Aqua trio, The Ebony Hillbillies were there to engage. With a funky, blues-influenced bass, it felt like they might jam in a singable, danceable way for hours. In fact, for reasons best known to themselves, the venue kicked them offstage and kicked the audience out very promptly at 10pm, spoiling the party vibe that they were generating.

Until, and even after, that moment lead singer Gloria — herself old enough to be Aqua’s great-aunt — was rocking and twerking up the joint. Making a virtue of the small turnout she got into the audience and got them to participate. First, in an extended jam, responding to the news that someone told her that “Her baby been thrown in jail,” she got everyone to sing how much they needed to “Get my baby out of jail” and then she went around to jokingly seduce the menfolk of all ages, leading to much amusement while the bassline kept the beat and the crowd kept clapping.

Though his urgings had brought the gig into existence, Lockwood kept his mouth far from the mic, which for me, as a fan of his initiatives (The Sway Machinery, and The Nigun Project among others), was a disappointment. Though the event was advertised as a community summit, there wasn’t much mingling of the bands. Temple on accordion and Aqua on fiddle sat in on one of the Hillbillies’ numbers but they didn’t do very much. But the fusion was present elsewhere, with the interplay between musicians and the crowd.

With a drummer (A.R.) who’d played around The Beatles and sounded like he could keep the beat spicy for another 60 years, the Hillbillies kept an effortless jam — the strings and the skins taking turns (alongside “Glo”) to spin out virtuosic, fun solos. It made no difference that a mostly Black band, singing mostly straight lyrics, were playing to a mostly non-Black, significantly non-straight crowd. Everyone, from ages 20-80 and beyond, was there to listen and to party.

And that’s how Brooklyn does it.

As the moon blotted out the Central Park sun earlier in the month, the hottest sales items from vendors long out of eclipse glasses were “Brooklyn” hats.

For a couple of decades now, the borough at the near end of Long Island has been a byword for authentic, hip, artisan, art. Manhattan’s bland capital has blanched the island, but its southern brother continues to represent.

The first recorded Jewish settler of Brooklyn was the Sephardi Jacob Barsimson, who arrived in August 1654 on a passport from the Dutch West India Company. For the last five centuries, then, Jews have been brushing up against the rest of the tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free. In our trying days of political tribalism, it’s better to share and share alike — to play at each other’s parties than to shut the doors and trumpet at the walls.

As Aqua writes on her website, as a permanent minority for millennia, Jews were a vector and a medium for cultural curiosity and sharing. “Jews are a part of the interwoven cultural texture of Transylvania, both past and present; and also of America; and of all the places around the world we’ve put down roots.” And if that means loving thy neighbor’s fiddle, so be it.