The hugely influential record label that unites Albert Einstein, Bob Dylan and Bernie Sanders lives on

Founded by Moses Asch, Folkways continues to be a repository for underappreciated voices

Pete Seeger recorded nearly 50 albums for Folkways. Photo by Getty Images

The list of record labels founded or co-founded by Jewish entrepreneurs during the 1940s and 50s is a long and luminous one. But as important as such legendary imprints as Atlantic, Chess, King, Modern, Roulette, Savoy, Scepter, Specialty and Verve were, it can be argued that none were as uniquely influential — or as intrinsically Jewish — as Folkways Records. And certainly, none of the others boasted an origin story involving Albert Einstein.

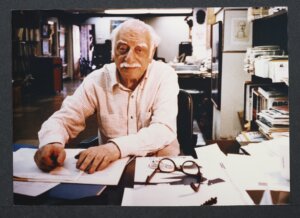

Though the story has been embellished considerably over the years, not least in retellings by Folkways founder Moses “Moe” Asch and folksinger/activist Pete Seeger (who recorded nearly 50 albums for Asch’s label), the seed that eventually flowered into Folkways was certainly planted during a 1939 dinner conversation between Asch, his father Sholem — a prominent Yiddish-language novelist and leftist intellectual — and the Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist. Einstein and the elder Asch were friends, and both men were actively sounding the alarm at the time about the looming shadow of the Third Reich, and encouraging the US and other governments to accept Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied European countries.

The younger Asch, then an audio engineer in his mid-thirties, traveled with his father to Einstein’s home in Princeton, New Jersey, to record Einstein’s messages to European Jews on a portable recording set-up, with the resulting acetates to be broadcast overseas via shortwave radio. Over dinner after the recording session was finished, Moses told the physicist about his dream of making and releasing recordings that would “describe the human race, the sounds it makes, what it creates,” with a special emphasis on American folk music, which was generally ignored by the bigger American record labels of the day. Einstein encouraged Moses to follow his dream; one account of the conversation has Einstein saying, “You’re right, Americans don’t appreciate their own culture. It would take a Polish Jew like you to make them appreciate it.”

While those exact quotes may well be apocryphal, there’s no question that the Warsaw-born Moses Asch went on to make a profound impact upon American culture with Folkways Records. Founded in 1948 (on the heels of his short-lived Asch and Disc labels), Asch’s Folkways imprint was a mainstay of the American folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s, releasing classic recordings by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Lead Belly, as well as such crucial compilations as 1956’s Banjo: Three-Finger and Scruggs Style — the first full-length bluegrass album ever released — and Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, a massively influential three-volume, six-record set that introduced American folk, blues and country music recordings made from 1926 to 1933 to a new generation of folk musicians and music lovers. “I envisioned myself recording for Folkways Records,” Bob Dylan would later recall in Chronicles: Volume One. “That was the label I wanted to be on. That was the label that put out all the great records.”

Asch didn’t limit Folkways to American folk music, however. The 2,168 titles that the small label managed to put out between 1949 and Asch’s death in 1986 (at an average of over one new release per week over that span) include poetry, spoken word, instructional, historical, documentary and natural sound recordings, as well as traditional, ethnic and contemporary music from around the globe — Folkways was releasing “World Music” decades before such a designated genre ever existed. Though most of Folkways’ releases were not overtly political, there was certainly a socially progressive sensibility behind the label and its mission.

“People have different views of what my father’s vision was,” Moses’ son Michael Asch told me. A professor in the Anthropology department at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, he also serves as an advisory board member for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, the nonprofit record label founded by the Smithsonian Institution in 1987 to preserve and promote awareness of the Folkways catalog, which the Smithsonian acquired after his father’s death. “People always talk about Folkways being like an ‘encyclopedia of sound,’ and I don’t really buy that. Because if it’s an encyclopedia, then you’re trying to capture one of everything, but that’s not what he did. He really focused on people whose voices weren’t heard — and in particular, people whose voices weren’t heard because they were being discriminated against, or because they’d been blacklisted. Those were the things that he thought people should hear.

“I think that was more of his motivation, to try to elevate these voices,” he continued, “the political sensibility of Folkways was about finding voices that were unrepresented and bringing them forward. He had this humanistic idea that if people could hear what other people were like, if we could understand each other’s cultures, that we could get along and work with each other. He was part of a movement that was trying to create this world in which people wouldn’t hate each other.”

This sensibility likewise informed the Jewish releases in the Folkways catalog. While the label has put out dozens of albums devoted to the preservation of the Yiddish language — including Ruth Rubin and Pete Seeger’s Jewish Children’s Songs and Games from 1957 — Asch also sought out Jewish music of non-European origin; by releasing recordings that showcased the diversity of the global Jewish diaspora, Asch hoped to combat the idea of Jews as a monolithic and homogenous group. This commitment to diversity is exemplified by such Folkways releases like Babylonian Biblical Chants, a 1959 album by Iraqi Jew Ezekiel H. Alberg, the 1978 compilation The Yemenite Jews, and two albums by the self-proclaimed “Jewish Soul” quartet The Voices Four. Though released by Smithsonian Folkways nearly 20 years after his death, the Grammy-nominated compilation Abayudaya: Music from the Jewish People of Uganda is very much of a piece with Moses Asch’s inclusive diasporic vision.

(Fun fact: One of the many Jewish “artists” on Folkways roster is Sen. Bernie Sanders. A few years before going into politics, Sanders wrote and produced the label’s 1979 spoken word release Eugene V. Debs: Trade Unionist, Socialist, Revolutionary: 1855-1926.)

“My father was not religious at all,” says Michael Asch. “I think that his attitude towards the Jewish culture was that there were a variety of reflections of it that went beyond a religious kind of sensibility — that there was some kind of community sensibility that went beyond the limitations of what it means to be Ashkenazi, and so on.”

Folkways was a unique label in other respects, as well. Asch took a documentary approach to recording, and stubbornly refused to employ multi-tracking, stereo sound, outboard sonic effects or other such technological developments that emerged in the recording world from the 1950s onward. He preferred instead to record music or speech through a single microphone placed for optimum balance, without any adjustments made to the bass or treble frequencies. “He cared deeply about recording in ways that the listener could hear what the actual sounds were,” Michael Asch explained. “They didn’t boost anything or reduce anything; how it sounded was the way it was.”

Which is not to say that Asch was averse to a little bit of editing magic after the fact. “The Folkways record my father loved the most was the interview he did with W.E.B. DuBois,” Michael Asch referring to 1961’s W.E.B. DuBois: A Recorded Autobiography, Interview with Moses Asch. “He said that it was the best record he ever made, because he was able to take his questions completely out of the recording, and when Du Bois spoke it sounded like he was speaking with no interruptions.”

As his devotion to no-frills recording might suggest, Asch was — unlike just about everyone else in his label-owning peer group — completely unmotivated by commercial considerations. “The obligation of the company is to maintain the office, the warehouse, the billing and collection of funds, to pay the rent and telephone, etc.,” he declared towards the end of his life. “Folkways succeeds when it becomes the invisible conduit from the world to the ears of human beings.”

With this in mind, Asch insisted that every single release in his catalog should remain in print for future generations, regardless of how well (or how poorly) they sold. “He didn’t think that things should be in or out of the catalog based on sales figures,” Michael Asch said. “If it added intrinsic value, it should stay in the catalog. There were a couple of things where a community objected to having certain recordings of their music or ceremonies in the catalog, and he’d take it out; but he never took anything out for commercial reasons.”

Indeed, one of the conditions of the Smithsonian’s Folkways acquisition was that the institution would continue to adhere to Asch’s “no deletions” policy; to this day, over 75 years since Folkways’ first releases, the entire Folkways catalog remains available for purchase and streaming. And since 1987, Smithsonian has further expanded on Asch’s immense legacy, adding the catalogs of several important folk-oriented indie labels (including Arhoolie, Folk-Legacy and Stinson) to the collection, and releasing over 375 new recordings that (as the Smithsonian Folkways website puts it) “document and celebrate the sounds of the world around us.”

You’ve Been a Friend to Me, a new Smithsonian Folkways compilation of recordings by the late vocalist Sonya Cohen Cramer, is not only a continuation of Asch’s vision (and another musical example of the diversity of the Jewish experience), but also very much a Folkways family affair. Sonya Cohen was born in 1965 to John Cohen of The New Lost City Ramblers — a folk revival string band heavily influenced by the Anthology of American Folk Music, who also recorded extensively for Folkways — and Penelope Seeger, the younger sister of fellow Folkways artists Mike, Peggy and Pete Seeger. Sonya was also Asch’s goddaughter; her parents took her with them to the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where her Uncle Pete dedicated the final evening’s performance to her, saying that she represented hope for the future. (That same night would culminate in a now-legendary performance by the newly electrified Bob Dylan, whose melding of Folkways influences with rock and roll enraged folk purists like Pete Seeger.)

After graduating from Wesleyan University, Sonya juggled a graphic design career with her musical pursuits, which included singing for the critically acclaimed folk-fusion group Last Forever, a collaboration with musician and songwriter Dick Connette inspired by songs of the American folk tradition. Sonya also worked for Smithsonian Folkways in the early 2000s, ultimately designing 64 album covers for the label.

The title track of the collection, which spans nearly 30 years of her recordings, was originally published as sheet music in 1858, and was popularized by a 1936 recording by the Carter Family. Sonya recorded the song in 2014 with Elizabeth Mitchell and Daniel Littleton of the folky slowcore band Ida, and it became something of a theme song for her as she dealt with the challenges of the cancer that would take her life the following year. Listening to her unadorned and heartfelt vocals on the Lead Belly-popularized “In the Pines” and the English folk song “Black Jack Davey,” one is struck not only by how powerful these venerable songs still can sound with the right interpreter, but that Moses Asch would have been extremely proud of his goddaughter.