Is Israel’s Most Famous Playwright Too Political For His Own Country?

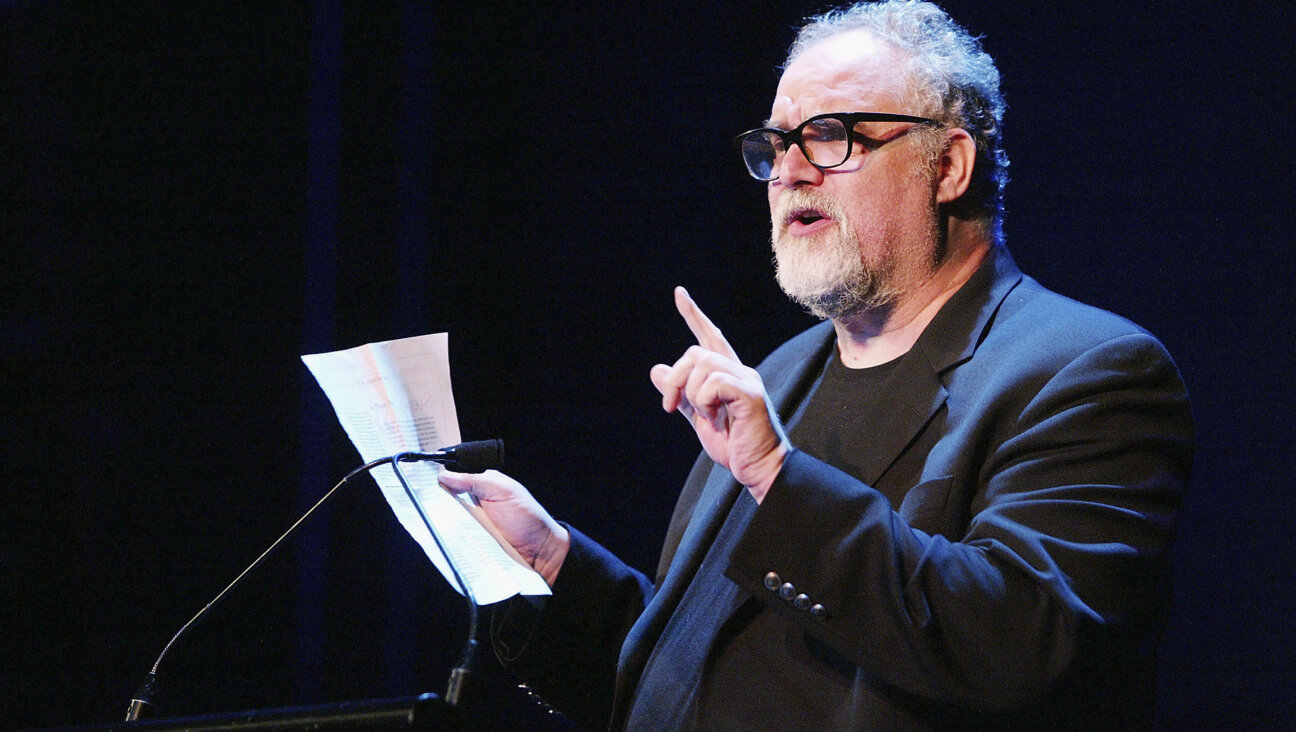

Joshua Sobol Image by Getty Images

In 1985, “Palestinian Girl,” a drama by Joshua Sobol, Israel’s most famous and prolific living playwright, premiered in the Haifa Theater. A story about a love affair between an Israeli man and a Palestinian woman whose relationship is being destroyed by right-wing thugs, the play was controversial, but a huge success. This was a few years before the First Intifada started, and the term “Palestinian” was still very taboo in Israel.

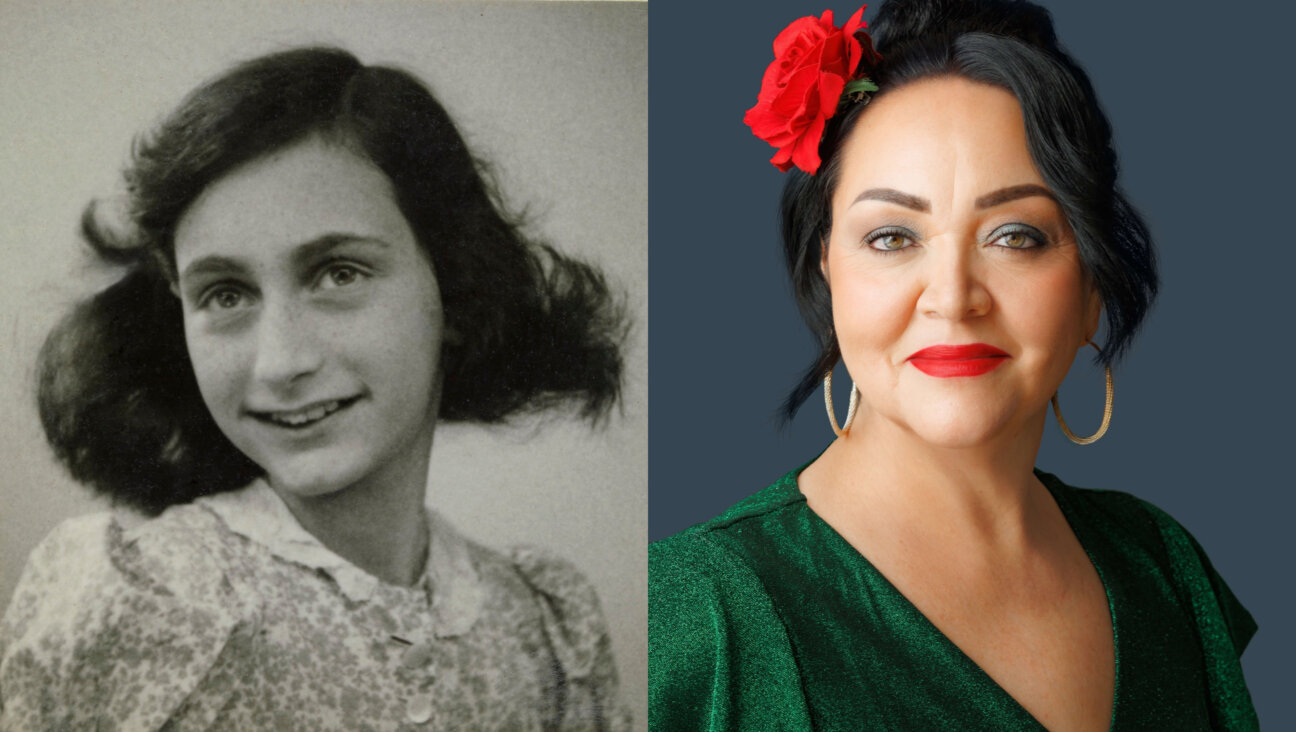

Over 30 years later, Sobol, 78, says he has been unable to find a home in Israel for his newest play. Instead, “The Last Act,” — which concerns an Israeli actress and Palestinian actor whose cooperation on the adaptation of a play ends in tragedy — will be staged in May in Boston by a small nonprofit production company called Israeli Stage, which was founded in 2010 with the stated mission of “sharing the diversity and vitality of Israeli culture through theater.”

Sobol says he sent the play to three public repertory theaters in Israel — the Cameri in Tel Aviv, the Haifa Theater, and the Khan in Jerusalem — but nobody was interested. “I didn’t bother sending it to some of the other theaters because of previous frustrating experiences I had with them over even less subversive plays,” he told me. “I am familiar with the system; I couldn’t have pushed more.” He added that the smaller private Tzavta Theater and fringe Arab-Jewish theater did express interest but were unable to find the budget for it.

Sobol is best known for “Ghetto,” a play that premiered in 1984 and told the story of the theater Jews created in the Vilna Ghetto during World War II. It has been translated into 20 languages and performed in 25 countries. This year he will be directing its debut in China. Sobol, who in 2009 won the Israeli Theatre Award for lifetime achievement, says this is the first time he has not been able to have one of his plays staged in one of the country’s main theaters — which rely on state funding.

According to Sobol, Israel’s leading public theaters — of which there are eight around the country –— are avoiding controversial materials. “They are trying to be harmless,” he said. “Our theaters are harmless and that also makes them tasteless. Theaters should become much bolder and delve into conflict.”

In recent years, there has been an increase in cases in Israel in which art with left-wing political content — specifically work that contains narratives that criticize the army or humanize Palestinians — have been stifled or outright censored by a combination of government efforts and rightwing grassroots pressure. Theater is one of the most popular of the performing arts in Israel, so it is not surprising that it has become a target. Israel’s only Palestinian theater, Al Midan, in Haifa has experienced a significant cut in government funding in recent years because of the 2014 play “A Parallel Time,” which includes the story of a Palestinian prisoner convicted of murdering an Israeli soldier in the 1980s. In 2017, Sobol withdrew his play from an annual fringe festival in Acre along with all the other artists in protest and solidarity with Israeli actress and playwright Einat Weizman, whose play about Palestinian prisoners was rejected.

Joshua Sobol with Israeli stage co-founder Guy Ben-Aharon. Image by Courtesy of Israeli Stage

“Israel is less tolerant than 20-30 years ago. I think there is self censorship, which is worse than governmental censorship,” Sobol said, referring to the phenomenon in which public theaters and other venues prefer not to take on controversial work that may get them in trouble.

Sobol is familiar with controversy. In 1987, while serving as artistic director of the Haifa Theater, he wrote and produced the play “Jerusalem Syndrome,” a sharp critique of Jewish Zionist fanaticism that drew a parallel between the Roman persecution of Jews during the Second Temple Period and Israel’s occupation of the Palestinians. It provoked angry protests, and the theater shut it down after a few months. Sobol subsequently left his position at the Haifa Theater to focus strictly on writing.

But according to Haifa Theater artistic director Moshe Naor, the company works with challenging materials all the time, and even performed one of Sobol’s older plays, “The Night of the Twentieth,” just a couple of years ago. “No one is boycotting Sobol,” Naor said, adding that Sobol writes a lot of plays, so it is logical that some hit, and some miss. “If I had more worthy political materials, I would use them,” Naor said. In 2011, the theater performed “Ulysses on Bottles,” a play that addresses Israel’s siege of Gaza. And “Ghetto” has had several runs at the Cameri in recent years.

Noam Semel, who worked with Sobol at the Haifa Theater in the 1980s and then served as general director of the Cameri Theater for 25 years, says he doesn’t believe the failure of “The Last Act” to premiere in Israel is due to political reasons, though he does admit “there is a zeitgeist in which the big repertory theaters are not putting their legs in the mud. The topic [occupation] is no longer as dramatic.”

Sobol wrote “The Last Act” about two years ago, when there was a surge of Palestinian stabbing attacks across Israel. “At the time, members of the government called on citizens to use their weapons and shoot to kill if they witnessed a terrorist attack,” Sobol said. “There was that lynching In Beer Sheva [when an African asylum seeker was beaten to death by Israeli civilians during a terror attack in the central bus station because they wrongly assumed he was the terrorist]. People had overwrought nerves. I wanted to write a play about this atmosphere.”

Spoiler alert: “The Last Act” is set in present day Israel. It concerns an Israeli Jewish actress, Gilly and a Palestinian actor, Djul who are performing an adaptation of a 19th-century August Strindberg play, “Miss Julie,” about star-crossed lovers. Gilly’s husband Ethan is a Mossad agent and he and his boss believe Djul is pretending to be an actor, but is in fact a Hamas operative trying to kidnap Gilly in order to exchange her for Palestinian prisoners. When Ethan walks in on them rehearsing a part where Djul is holding a (prop) knife up to Gilly, he shoots him. Gilly then grabs the gun and commits suicide. The play has a very literal message for Israeli audiences: “Let’s try to stop reacting so violently to any attempt at Israeli and Palestinian cooperation,” Sobol says.

In the Israeli Stage production, Djul will be played by a young Palestinian actor named Louis Abd El Massih, an Israeli citizen from Nazareth. All the other actors are American, none of them Jewish. This is the first time Israeli Stage has hired a non-American actor and flown him in from abroad for a role. Director Guy Ben-Aharon said Abd El Massih has been able to provide critical context for the American actors about the experience of Palestinians in Israeli society. During rehearsals, members of the cast have drawn parallels to the experience of black men being shot by white police officers in America. The mass shooting of protesters in Gaza has also come up in conversations.

Israeli Stage was founded by Guy Ben-Aharon, an Israeli native who moved at age 9 to Massachusetts and studied theater at Emerson College. Ben-Aharon says the impetus for creating Israeli Stage was his own personal interest, having grown up in Israel, to bridge American and Israeli cultures. He first met Sobol in Israel in 2012, and invited him to work together. Last March, Sobol was a playwright in residence with Israeli Stage, where he presented lectures at over half a dozen campuses on theater as a form of resistance.

“Many groups with the word ‘Israel’ in them — their end goal is Israel. For us, it is a template, a starting point. The end point is the audience,” Ben-Aharon said on the phone during a break from rehearsals. “Theater exists to ask difficult questions. Theater exists as a public forum to open people’s hearts and minds, and how timely it is to open their hearts and minds to this reality. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict has been going on for 70+ years; it is our duty as theater makers to explore the narratives and humans who are entangled within it.”

“The Last Act,” which premieres May 18, has already garnered some pushback. Ben-Aharon, who has been accused of putting on “anti-Israel” programming in the past (for the 2015 staging of “Ulysses on Bottles,”), says he has received dozens of emails from people who have taken issue with the upcoming production. He said that one audience member claimed that Sobol does not deserve a voice on Israeli Stage because he has been open about his political views. Another reaction Ben-Aharon cited takes issue with the fact that the name “Israeli Stage” gives the impression that it represents Israel — but in fact will be showcasing a work that gives a negative impression of the country.

“This is the first time I feel the tide has shifted,” Ben-Aharon says. “These are all playwrights who live in Israel, who write with concern and love for the place. How dare we question that?” Ben-Aharon says, adding, “We never said we were going to be an Israel advocacy group. That’s just not interesting.”

When I asked Sobol whether he feels betrayed by his own country, he described a society contaminated by corruption, inequality, and poverty, and most of all complicity in the status quo. “I wrote this play out of despair and rage.” he said.

He believes that since Rabin’s assassination, Israelis have simply come to terms with being an occupying power that can continue to oppress Palestinians. “All I can do is sound the alarm bells. But when those are silenced, all I’m left with is speaking to the few that are willing to listen to the voices disturbing the joy and merriment.” Sobol said he hopes the premiere in Boston will echo in Israel and eventually bring it to a main stage there, for an Israeli audience.

Mairav Zonszein is an Israeli-American journalist who writes about Israeli politics, American foreign policy and human rights. She is a contributor to +972 Magazine and her work has been published in The New York Review of Books and The New York Times.