Why Arthur Miller paid a price for greatness

In John Lahr’s new biography, the ‘Death of a Salesman’ writer’s inner life explains the plays we know

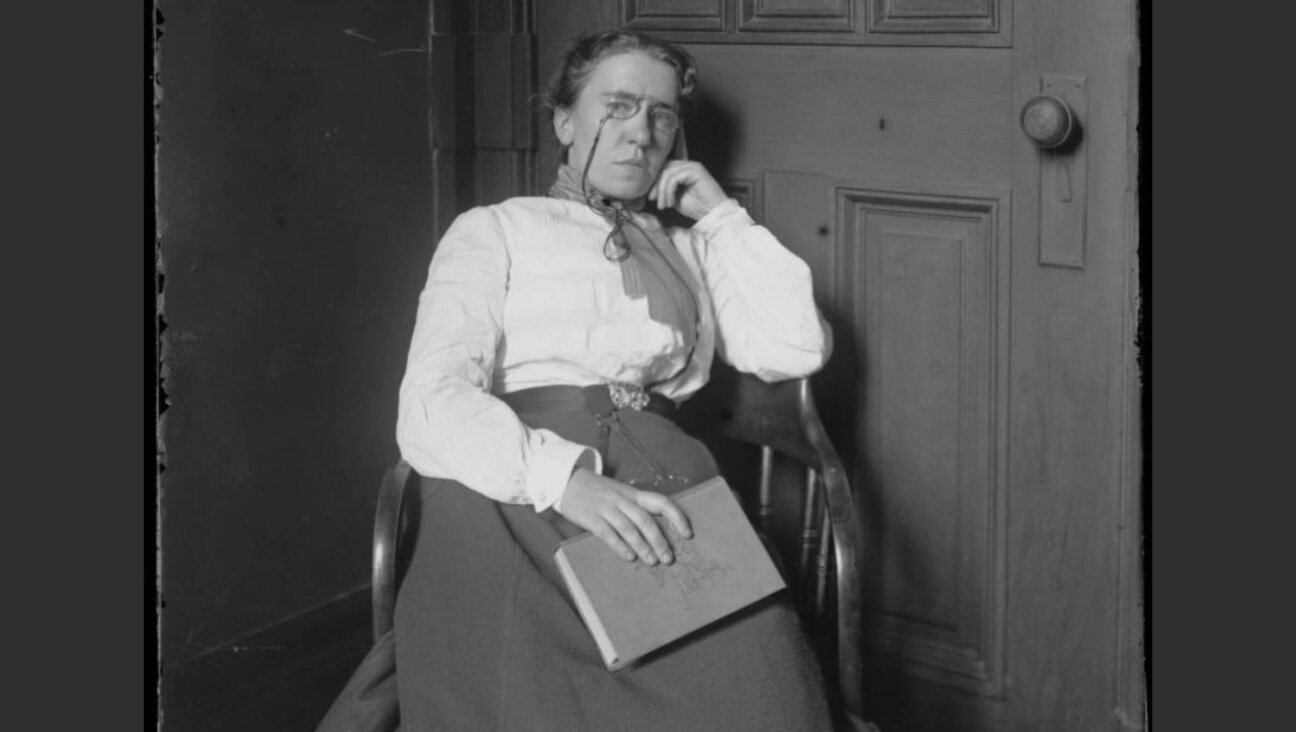

Arthur Miller, circa 1955. Photo by New York Times Co./Archive Photos/Getty Images

Arthur Miller: American Witness

By John Lahr

Yale University Press, 264 pages, $26

When he was a young, unknown playwright, Arthur Miller bristled over an early setback.

In 1938, the Group Theatre was interested in his comedy “The Grass Still Grows,” about a coat factory owner and his sons. But, as Miller wrote to his mentor, Kenneth Rowe, the Group had already met its quota for a certain type of material.

“Finally they decided they didn’t want to do another Jewish play this year,” Miller wrote.

Per Miller, a Jewish producer for the Group feared antisemitic reprisal over the play’s content. An “Aryan” was willing to back it, though, and Miller expressed his hopes that this patron “makes a million on it and gets the commendation of the Jewish Daily Forward in the bargain.”

(The play never ran and so, alas, there was no plaudit from this publication.)

Miller’s letter to Rowe, which appears in John Lahr’s new book, “Arthur Miller: American Witness,” may yield a clue as to why the playwright shifted gears to less denominational fare early in his career. While his collegiate work, informed by his labor reporting and his leftist awakening at the University of Michigan, took his Jewish family life as its subject, he went on to chronicle the Ibsenesque undoing of a gentile war profiteer, Colonial Puritans in Salem and, of course, a salesman who, while probably Hebraic in origin, is never identified as such.

But in a slim, if uneven, biography Lahr makes the case that all of Miller’s work was shaded by his personal life. Lahr’s method of finding autobiographical parallels in Miller’s themes and characters offers mixed, but occasionally revelatory, results.

The book goes more or less chronologically through Miller’s biography and oeuvre, breaking down the writer’s subconscious sources of inspiration.

In “All My Sons,” Miller’s first hit on Broadway, the gregarious patriarch Joe Keller is an avatar of Miller’s illiterate, prosperous and ultimately feckless father, Isidore. Joe’s wife, Kate, who maintains her husband’s innocence in the sale of faulty airplane parts, embodies Miller’s delusional and secretive mother Gussie (she and Isidore lied to their children about their financial situation after the 1929 market crash, a detail Miller would utilize much later in the far more Jewish “The Price”).

“Art was not a writer who made up stories,” Elia Kazan is quoted as saying. “He had to have a living connection with a subject before he could make a drama of it.”

Kazan and Miller, whose friendship never fully recovered from the director’s decision to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee, serve as a key relationship for Lahr, but their fallout is also the source of one of the biographer’s bigger leaps.

Lahr says that when “A View from the Bridge,” about a longshoreman who reports his Italian cousins to immigration, was revised, Miller tailored the final lines, “I mourn him — I admit it — with a certain alarm,” to an audience of one.

“Miller seems to speak across the footlights to Kazan,” Lahr writes. “His rueful weasel words play both as a way of forgiving Kazan his trespasses, and, by extension, allowing Miller to forgive his own.” Maybe. But this could be overstating it a bit.

Lahr’s appraisal of Kazan and Miller’s final collaboration,“After the Fall,” inspired by the playwright’s doomed marriage to Marilyn Monroe, is more credible: “Miller, who had refused to name names to HUAC, now stood accused of informing on Monroe.”

The long passages Lahr devotes to Monroe and Miller’s romance have a tendency to dip into melodrama and familiar cliches. (“She had a show-stopping body but an untutored mind”; in Miller’s “emotional desert” she was a “kind of oasis” and he “a kind of anchor — a father figure … a teacher, a guide.”)

It’s a shame that those chapters, certainly pivotal to Miller’s life and transition to outright confessional work, offer no great new insights, beyond Lahr’s dubious conjecture that Abigail Williams, the teenage temptress in “The Crucible,” may be a stand-in for Monroe.

At its best the book captures the conditions and context that made Miller a dramatic and moral force. The fact that Miller, so sympathetic to the working man after the success of “All My Sons,” took a night shift job in a Queens box factory, is more revealing than any dialogue he may have cribbed from his and Monroe’s marriage for “The Misfits.”

Following a prologue largely lifted from Lahr’s very good 1999 New Yorker profile, which locks down a very Jewish and personal provenance for “Death of a Salesman,” and an analysis of Miller’s one novel, the oft-forgotten parable about antisemitism, “Focus,” Lahr offers a diagnosis for the writer and his body of work: survivor’s guilt for what made his life possible.

Miller earned an education, literary success and a medical exemption from World War II, unlike his older brother, the more studious and idealistic Kermit, who fought in the Battle of the Bulge and became a carpet salesman. (According to Kermit’s son Ross, his father traded his dream of graduating NYU for toiling in the family coat business, so Miller could stay on at the University of Michigan.) It’s in this fraught dynamic that Lahr’s biography finds a compelling writer’s statement.

“I am not inventing stories and entertainments, but making a record of my own struggle to find reality,” Miller wrote to Kermit, explaining why he was working instead of attending Ross’ bar mitzvah. “It entails a price, a loss, a sacrifice which I cannot regret without regretting my work itself.”

As Lahr notes, the letter almost perfectly mimics the rationale for selfishness offered by the successful surgeon brother, Walter, in Miller’s last major play, “The Price.”

In that play, the seething resentment of two brothers selling their parents’ furniture boils over, as Victor, a police sergeant, fulminates over his unfinished degree and the $500 nest egg their parents, brought low by the Depression, never told them about. The wealthy Walter is condescendingly beneficent about his “debt” to his brother; Victor plays the morally superior martyr.

In his memoir “Timebends,” Miller wrote that “the characters were not based on Kermit and me,” a line Lahr calls disingenuous. What Lahr does find genuine is a stage direction following the brothers’ parting of ways.

After Walter watches Victor leave, he privately succumbs to the shame of his success. “The flick of a humiliated smile passes across Walter’s face. He wants to disappear into air.” This, Lahr writes, is “an admission in theater that Miller could never make in life.”