How ‘Hester Street’ made its way to the stage

Joan Micklin Silver’s classic film debuts as a play at Theater J

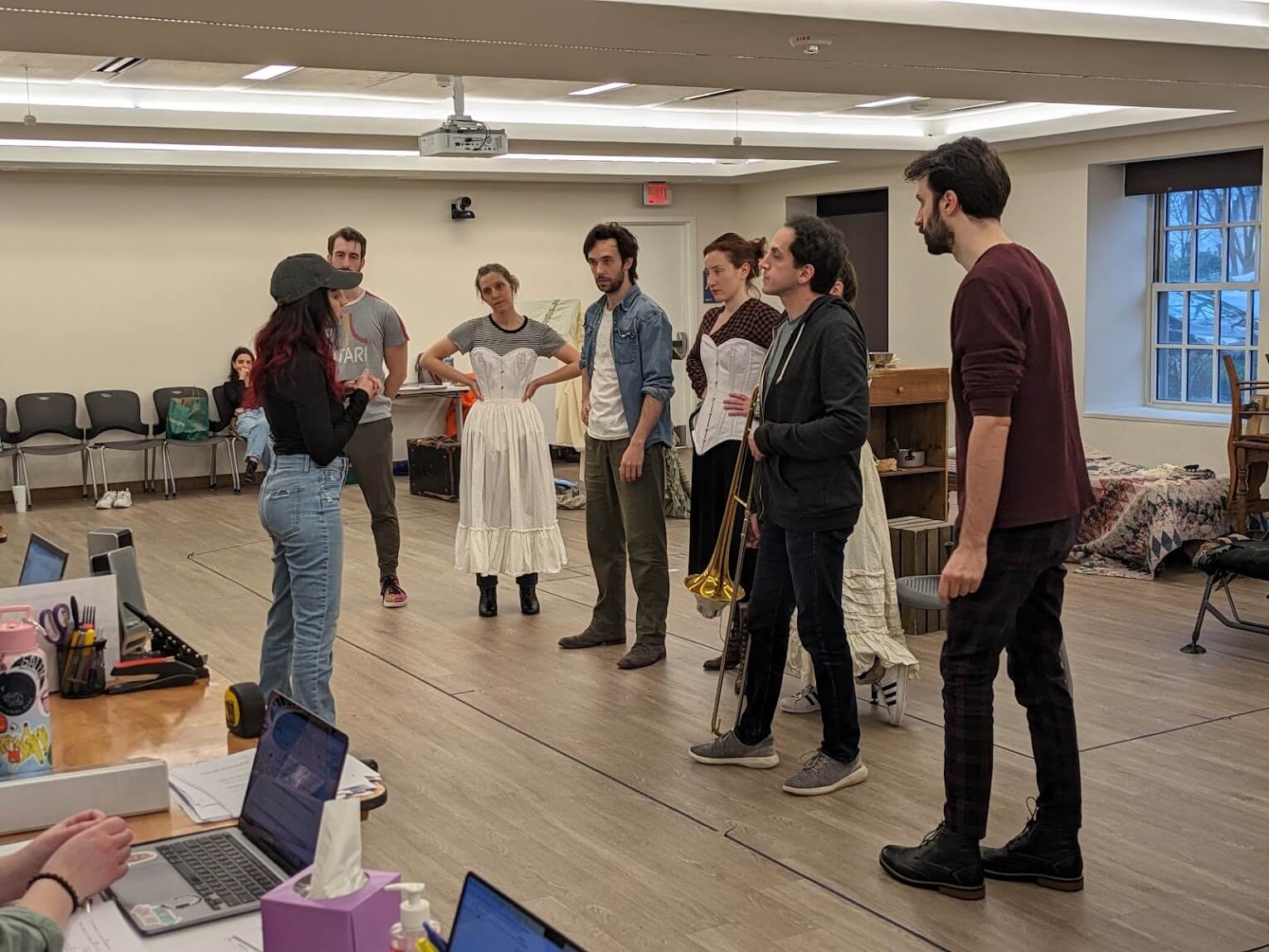

The cast of Hester Street rehearse on March 9. Courtesy of Theater J

When theater producer Michael Rabinowitz reached out to Joan Micklin Silver to adapt her film Hester Street for the stage in 2015, she didn’t jump at the opportunity.

Before answering his email, Silver called up independent film producer Ira Deutchman, who had been helping her tie up loose ends with the rights to her films since the death of her husband. When Deutchman asked Silver how she felt about the idea, she was honest.

“She said, ‘Well, you know, I don’t understand why — the movie exists. Why would you want to turn it into something else?’” Deutchman recalled.

He suggested she take the meeting and hear Rabinowitz out. He made an impassioned, and personal, pitch.

Rabinowitz had seen the film as a child. He fell in love with the its tone and specificity and, as an adult, discovered its basis, Abraham Cahan’s novel Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto, which gave him greater insight into the character of Jake, an immigrant striving to be all-American, played in the film by Steven Keats.

“I was really fascinated by the fact that he had a lot of anger towards his family, towards his father, for not giving him the tools that he actually needed to succeed in the States,” Rabinowitz told me. Growing up Orthodox, and leaving the fold, he saw himself in Jake’s struggle.

Rabinowitz expressed these connections — and his idea to stage Hester Street as a play with music (though not as a musical) — to Silver and Deutchman. After he left the room, Silver turned to Deutchman to ask what he thought.

“I said, ‘I think it’s a brilliant idea,’” Deutchman said. “And she said, ‘Really?’”

In the end she came around to the idea, and now Hester Street, a Yiddish and English play with music, will debut March 27 at Theater J in Washington, D.C. Deutchman is co-producing, his first foray into the theater.

Silver, who died in 2020, was a trailblazer, writing and directing Hester Street (her husband, Raphael D. Silver, produced) as a black-and-white, bilingual film in 1975. Once she accepted the idea of a stage version, she was involved at every juncture from the time the project got going in 2015. One of the first steps was finding a playwright to bring it to life.

‘Putting on the suit of America’

Sharyn Rothstein hadn’t seen Hester Street before Rabinowitz shared it with her, hoping she might pen the play adaptation.

“I immediately fell in love,” said Rothstein, a playwright and screenwriter for shows like Suits and Orphan Black: Echoes.

Rothstein said that the movie recalled her own family history. Most of her forebears settled on the Lower East Side, including her great grandmother, who arrived at 16 by herself.

Getting to explore the film — and Cahan’s novella — “was kind of a dorky playwright’s dream,” Rothstein said.

Rothstein’s main goal with the script was to give each character a more fleshed out backstory. Key to that was Jake. While Cahan’s book is told through Jake’s perspective, he’s more inscrutable in the film.

“Jake, is really a much more, shall we say, tormented soul in the play,” Rothstein said. “He’s just putting on the suit of America, but it doesn’t quite fit.”

In the play, Jake literally confronts the ghost of his father, whose death makes him reconsider his own parenting, prompting him to bring his son, Yosselle and wife, Gitl, to New York from the old country.

To breathe life into the city with a small cast, Rothstein wrote in musicians, blending the sounds of klezmer and jazz, to stand in for the cross pollination of cultures in the New World. Joel Waggoner, who has arranged work for Randy Rainbow and Joe Iconis, wrote the music and songs, and the character Joe Peltner, who operates a dance studio, serves as a kind of Greek chorus.

Rothstein was most excited to write for Gitl — played in the film by Carol Kane, who earned an Oscar nomination.

“There’s a moment in the film, and it’s in the play as well, where instead of shyly leaving a scene or kind of retreating, she unexpectedly pulls up a chair — and that’s the moment I fell in love with her.” Rothstein said.

“I also saw in her a story of so many refugees who are coming to America right now,” Rothstein said. “I think it’s really important that we as American Jews remember our past and remember that we needed the kindness of others, and that we had to build lives from nothing.”

‘Don’t be afraid to sound Jewish’

A major part of the draw of the Hester Street film, and a piece pivotal to Gitl’s journey, is Yiddish. About half of Rothstein’s dialogue is in the mameloshn, which will appear in supertitles. Rothstein doesn’t speak the language and neither do the actors or the play’s director, Oliver Butler.

“I think it is a nice metaphor for what a person goes through in their own journey and transformation,” said Butler, who directed What the Constitution Means to Me on Broadway. “They’re sort of trying to figure out, ‘What do I leave behind? What do I let go of so that I can embrace this new life and the new world?’”

Getting the Yiddish right meant hiring Miriam Isaacs, a native Yiddish speaker and a retired professor of Yiddish language and culture at the University of Maryland, College Park.

“I turn to Miriam and say, ‘Is it coming across that way?’” Butler said. “So I myself am forced, in a sort of amazing way, to use translation as a part of direction.”

“To have her in the room is just like the biggest blessing ever because I can just turn to her and say like, ‘we need a word that’s like, not prostitute, but like not far from prostitute,’” Rothstein said.

Isaacs was sure she’d read Cahan’s novella at some point, but had mostly forgotten Hester Street, which she saw when it came out.

“Mostly what I remember about the film is that the actress had these weird eyeballs, very bulgy eyeballs with blonde lashes,” Isaacs said, referencing Kane.

Isaacs was given Rothstein’s script with the dialogue already translated, and has been working one-on-one with the actors. Pronunciation and accent work are a part of her instruction, but so is body language.

“I’m encouraging them to talk with their hands more, I’m encouraging them to sing Yiddish more in a kind of Talmudic cadence,” Isaacs said. “Don’t be afraid to sound too Jewish. Sound too Jewish — it’s OK.”

Isaacs said she also gave notes on particular lines of dialogue. At a moment where Jake is about to cut off the payot of his son, Yoselle, the script had Gitl saying “Du kenst nisht” (you cannot) to stop him. Isaacs said she would say “Du torst nisht” (“You may not.”)

In one instance, Isaacs said with a laugh, she provided a handy — and PG-13 — tip for pronunciation.

“The main character’s Gitl, but they were pronouncing it Gih-tl, which to me sounds awful,” Isaacs said. “So I said it’s the difference between ‘shit’ and ‘sheet’ — and that they heard.”

For those wondering, many of the film’s colorful Yiddish expressions — including Mrs. Kavarsky’s famed proclamation as delivered by Doris Roberts, “You can’t pee up my back and make me think it’s rain” — are preserved in the script.

Continuing a legacy

Hester Street takes place in 1896, the year Cahan published his novella and the year before he launched the Forverts as founding editor, but the team behind the play is very aware of its 2024 context, with immigration already a major talking point this election year.

“The immigrant experience is so central to this story of this country, and what that means,” said Hayley Finn, artistic director of Theater J. “It reminds us that many of us are descendants of people who are not of this land.”

In a reading in November, Rabinowitz said a monologue from Mrs. Kavarsky, Jake’s landlord, in which she recalls pogroms, felt different after Oct. 7.

“There’s something not only universal but everlasting about this piece,” Rabinowitz said.

Deutchman said the only regret is that Silver, who attended readings and always gave great notes, didn’t live to see the full production.

“What the play is doing is it’s preserving what was wonderful about the movie, but amplifying in ways that she couldn’t get to in the film,” Deutchman said. “And so it is actually justifying the very first question that Joan asked, which is ‘Why bother?’ And the answer is because it’s actually not only going to preserve Joan’s legacy on a certain level, but it’s also going to make it even richer.”

For tickets and more information about Hester Street, visit Theater J’s website.