She was a teenage runaway, German rock star and Berlin leading lady — now she’s playing Leonard Bernstein

Helen Schneider will embody the maestro in the Off-Broadway play ‘Last Call’

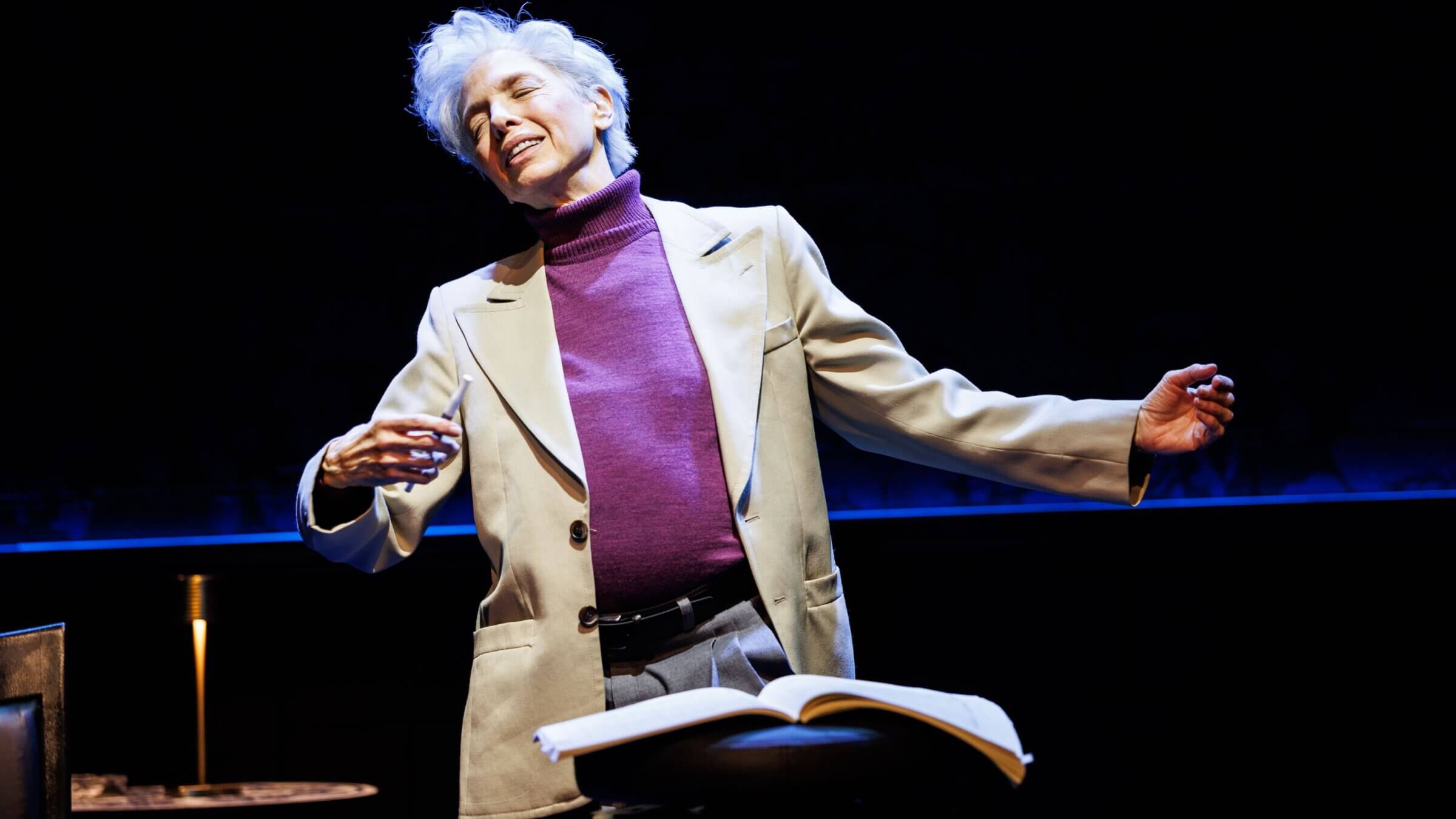

Helen Schneider as Leonard Bernstein, conducting some Brahms. Photo by Maria Baranova

Leonard Bernstein needs to “see a man about a horse.”

After excusing himself from a confrontational meeting with his bête noire, Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan, a genius who joined the Nazi party twice, the maestro of the New York Philharmonic begins an inner monologue as he approaches the urinal.

It’s a humanizing moment for a giant of 20th Century popular culture, but it requires some suspension of disbelief for the audience, and not for the reason you might think.

The scene is part of Peter Danish’s new play Last Call, about a chance 1988 encounter between Bernstein and von Karajan at the famed Hotel Sacher in Salzburg, Austria, in which the two senior citizens spar over their careers, creative philosophies and Karajan’s decision to stay in Germany under Hitler. The play is premiering this month Off-Broadway and in an unconventional, but quite effective twist of casting by German director Gil Mehmert, both of these “great men” are played by women.

Helen Schneider, the German-based, American-born actor who plays Bernstein, sees the creative decision as freeing theatergoers from their preoccupation with getting the gestures, tics and voices of famous figures exactly right.

“I think that if we start with women, that onus disappears a bit, because already we’re in the world of impression and nobody was interested in doing a reverse transvestite show,” said Schneider in the lobby of Manhattan’s New World Stages, still in costume as the maestro in a cream blazer and maroon turtleneck.

Schneider, who plays Bernstein with the hyponasal, Boston-tinged voice and nagging cough of his later years — most conspicuous in the word “Mahler” — was an early disciple of the conductor. A fourth-generation New Yorker, born in Brooklyn to Jewish parents, Schneider, 72, studied piano and says she was something of a prodigy.

“Bernstein was, for me, a god, and he was handsome, and he made classical music accessible,” said Schneider, who has lived in Germany since 2007, after charting as a rockstar there in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and in recent decades graced the stage as Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard and Sally Bowles in Cabaret.

“He had a way of speaking about music to embrace everybody,” Schneider said.

Bernstein’s televised Young People’s Concerts were a touchstone for Schneider, and his willingness to break down walls between genres, and to freely interpret classical music, was an inspiration as she left home at 17 to tour the Berkshires with a “crazy blues rock band.”

Her travels led her to Germany where she got a top 10 record with the song “Rock ‘n’ Roll Gypsy.” She left her recording contract behind after starring in the 1983 cult classic Eddie and the Cruisers, whose costars Ellen Barkin and Joe Pantoliano encouraged her to seriously pursue acting.

Bernstein, who bridged the classical and popular, set an example for how to lead an artistically eclectic life.

“In the process of studying for this role, I had a strange thing happen, because it felt kind of like when you finally find out who your parents really are,” Schneider said of Bernstein. She came to love him just as much, warts and all.

In Danish’s script, inspired by his discussion, over sacher torte, with a waiter at the Sacher Hotel, and quality-checked by musicians who worked under the baton of Bernstein and Karajan, that means accepting a certain streak of Jewish chauvinism in Bernstein. (Schneider doesn’t consider herself Jewish, saying “If people say to me, ‘Oh, well, but you’re just a non-practicing Jew,’ then I say, ‘Well, I don’t understand that, because I’ve never met a non-practicing Black person.’”)

When Karajan — played by German actress Lucca Züchner — calls him a Jewish nationalist, Bernstein declares the Jewish people are “the most compassionate and caring people in the entire world,” as a bit of klezmer clarinet kicks in.

Schneider, who lives in Hamburg, where she teaches singing and performance, paraphrased the line, applying it to Germans.“Of course, it has to do with the conscience from the Holocaust,” Schneider said. “So what? Whatever the reason is, it’s there now.”

But lately, Schneider and her friends have observed a changing Germany, that, with the support of people like Elon Musk and Steve Bannon, is failing to strike its typical balance between free speech and hate speech, leading to historic wins for a far-right party, the Alternative for Germany (AfD), for the first time since the end of World War II.

“That the AfD is even sitting in the legislature is kind of astonishing, but what’s happening here has terrified the entire world,” Schneider said of the United States, which she wouldn’t have returned to, if not for this play, which she believes is even more topical now for its discussion of Karajan’s failure to resist fascism.

While Schneider doesn’t identify as Jewish (and her thoughts on Bradley Cooper’s fake proboscis boil down to Lenny having a big nose — and big ears) the play makes explicit reference to Bernstein’s Jewish works — much more than Maestro.

Danish says the one true line from Bernstein, taken from a kind of catchphrase for anything difficult, was Bernstein’s assertion that speaking with Karajan is “more maddening than teaching my son Hebrew.”

Danish, who is Catholic, included a Yiddish saying: “If God sends you many sufferings, it’s a sign that He has great plans for you.” He said Schneider offered to translate it back to Yiddish, and now it’s in the show, causing some Jewish audiences members at early readings to tear up.

Even though taking on her former idol is a tall order, playing a man is not new for Schneider.

She would slip into male characters for her Kurt Weill revue, A Walk on the Weill Side, and played a “genderfluid” narrator role in Mehmert’s Der Ghetto Swinger, about the Holocaust survivor guitarist Coco Schumann. And while she returned to the tape often to channel Bernstein’s mannerisms and conducting style, she had a different point of reference for a bit of stage business that’s new for her: peeing standing up.

“I do remember how my partner did it,” Schneider said. “And so there were some moves that kind of stayed with me.”