America’s First All-Yiddish ‘Fiddler’ Is A Perfect, Bittersweet Portrait Of Jewish Joy

Steven Skybell as Tevye in the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene’s “Fiddler on the Roof.” Image by Victor Nechay / ProperPix

I was sick for my latest birthday, sniffly and feverish, yet I somehow found the wherewithal to force my gathered friends to watch the scene from “Fiddler on the Roof” in which the furious ghost of Frume Sarah rises from the grave. You know the one. Tevye, trying to convince his wife Golde to approve of their eldest daughter’s engagement to the tailor she loves, rather than a wealthy butcher, invents a dream in which the butcher’s late wife threatens death and destruction if her husband weds again. Over a grainy video from the 1971 film, in which Ruth Madoc’s Frume Sarah whirls and screeches, I felt an uncommon glee. Frume Sarah is terrifying, the witch who spooked my childhood. I love her.

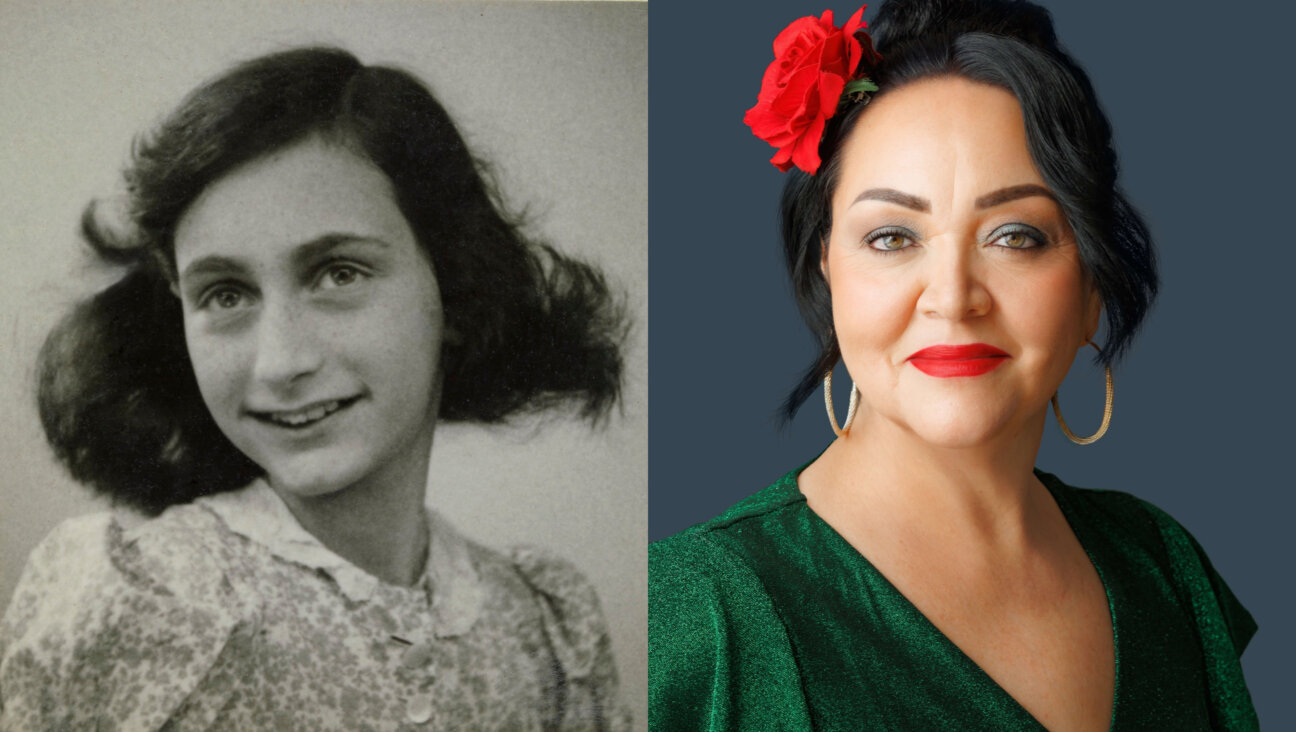

And how much more I loved her as Frume Sore, screeching in Yiddish instead of English, in the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene’s “Fiddler on the Roof,” the first all-Yiddish production of the classic musical to grace an American stage. (The translation comes courtesy of Shraga Friedman.) The Folksbiene’s Frume Sore is played by two people, rather than one: Jodi Snyder, as goth-glam a ghost as ever tormented a dairyman, sits atop some anonymous soul’s shoulders for the role, making Frume Sore quite literally larger than life. She’s hilarious and scary, ludicrous yet somehow absolutely convincing. If she visited your dreams, you wouldn’t let your daughter marry Leyzer-Volf, either.

This — but pre-ghost. Image by Victor Nechay / ProperPix

Yet Frume Sore is also a succinct embodiment of the many merits of the Folksbiene’s production, directed by the Broadway legend Joel Grey and choreographed by Staś Kmieć, with music direction by Zalman Mlotek. “Fiddler on the Roof” is a weird musical, one in which joy predominates despite the constant presence of desperate poverty and the only slightly less consistent threat of violence at the hands of Cossacks. No character better embodies that strange balance than Frume Sore, who, despite being dead, at risk of losing her precious pearls and vengeful to the point of murder, seems to have, well, a ton of fun haunting Tevye and Golde. As conjured by Tevye, Frume Sore may be confronting a matter of life and death, a true reckoning with a threat to identity, but she has a great time doing it.

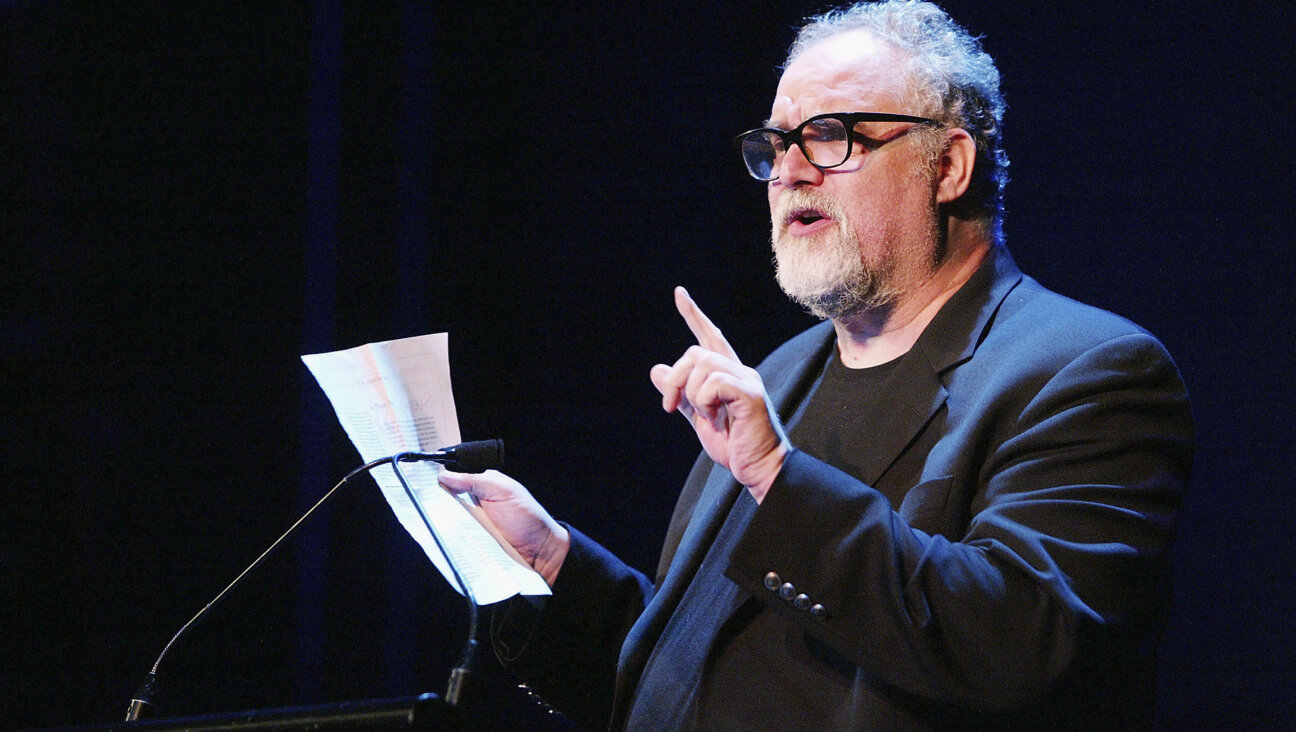

That attitude pervades the show. Life is rough, frequently terrible, yet Tevye, played by Steven Skybell, jokes with God with apparent earnestness. His humor doesn’t seem to be a mask for bitterness, or even a coping mechanism. To Tevye, a belief in God goes hand-in-hand with a belief in humor, and “Fiddler on the Roof” is clearly on his side. Under Grey’s direction, the yeshivniks who correct Tevye’s loose and often wrong attempts at quoting Torah are rigid to the point of ridiculousness. In the late song “Der Klang,” or “The Rumor,” Anatekve’s Jews treat the spreading of an increasingly exaggerated rumor about Tevye’s family as excellent communal entertainment, warping the truth willfully but not maliciously. In Anatevke, Judaism is about study and struggle and tradition, but also about pleasure.

The current relevance of “Fiddler on the Roof” is apparent, and registers with new immediacy in the age of Trump. The constable who makes a show of friendship to Tevye whilst brutally enforcing discriminatory edicts against the Jews takes on a fresh meaning; what’s scariest about him isn’t his cruelty, it’s his complete refusal to call things what they are. And the end of the show, in which Anatevke’s residents, forced from their homes, have no choice but to hope faraway countries will accept them, is a sharp rebuke to the coldness toward immigrants and refugees that has tainted our contemporary world.

But “Fiddler on the Roof,” I found, makes its most unique point about the less obvious subject of happiness. At the play’s end, as Anatevke’s Jews disperse — to Jerusalem, Chicago, Krakow, etcetera — Tevye holds to his jokes, but their tone has changed. They are determined, not organic. There is a great tragedy at hand: The forced abandonment of home, ancestors, community. But a smaller tragedy is happening too: The pleasure is going out of Jewish life. From the perspective of history, a perspective that Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick had when they penned “Fiddler on the Roof” in the early 1960s, that small tragedy appears great. The decades after Tevye’s exodus would be increasingly unkind to his ilk, and fatal to many of them. It would be a long time before Jews, as a group, would regain even a shade of the shared joy in daily life that “Fiddler on the Roof” depicts. Is that an accurate depiction? Probably not. But it brilliantly clarifies part of the sense, pervasive in American Judaism, that something essential has gone missing.

For that reason, a “Fiddler on the Roof” in Yiddish makes particular sense. The language of the lost world, bountifully expressive, is the appropriate framework for a show that revives a little-commented upon feature of that world. Through the efforts of the Folksbiene and its fellows, Yiddish is experiencing something of a contemporary resurgence. Perhaps other good things will follow in its wake. As Tevye and Golde do to ward off the evil eye: Spit thrice.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Most Popular

- 1

News Student protesters being deported are not ‘martyrs and heroes,’ says former antisemitism envoy

- 2

Opinion My Jewish moms group ousted me because I work for J Street. Is this what communal life has come to?

- 3

News Who is Alan Garber, the Jewish Harvard president who stood up to Trump over antisemitism?

- 4

Fast Forward Suspected arsonist intended to beat Gov. Josh Shapiro with a sledgehammer, investigators say

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Report: Trump scuttled Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities

-

Culture ‘Shtisel’ star Sasson Gabay is happy to be back playing a complex haredi Orthodox Jew in ‘Kugel’

-

Fast Forward Noa Argamani, ADL’s Jonathan Greenblatt among over a dozen Jews on 2025 TIME 100 list

-

Fast Forward US claims Mohsen Mahdawi’s activism could ‘potentially undermine’ prospect of peace in Gaza

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.