7 standout treasures from YIVO’s vast collection in New York

In honor of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research’s 100th birthday, we take a deep dive into the cultural institution’s massive Yiddish archive

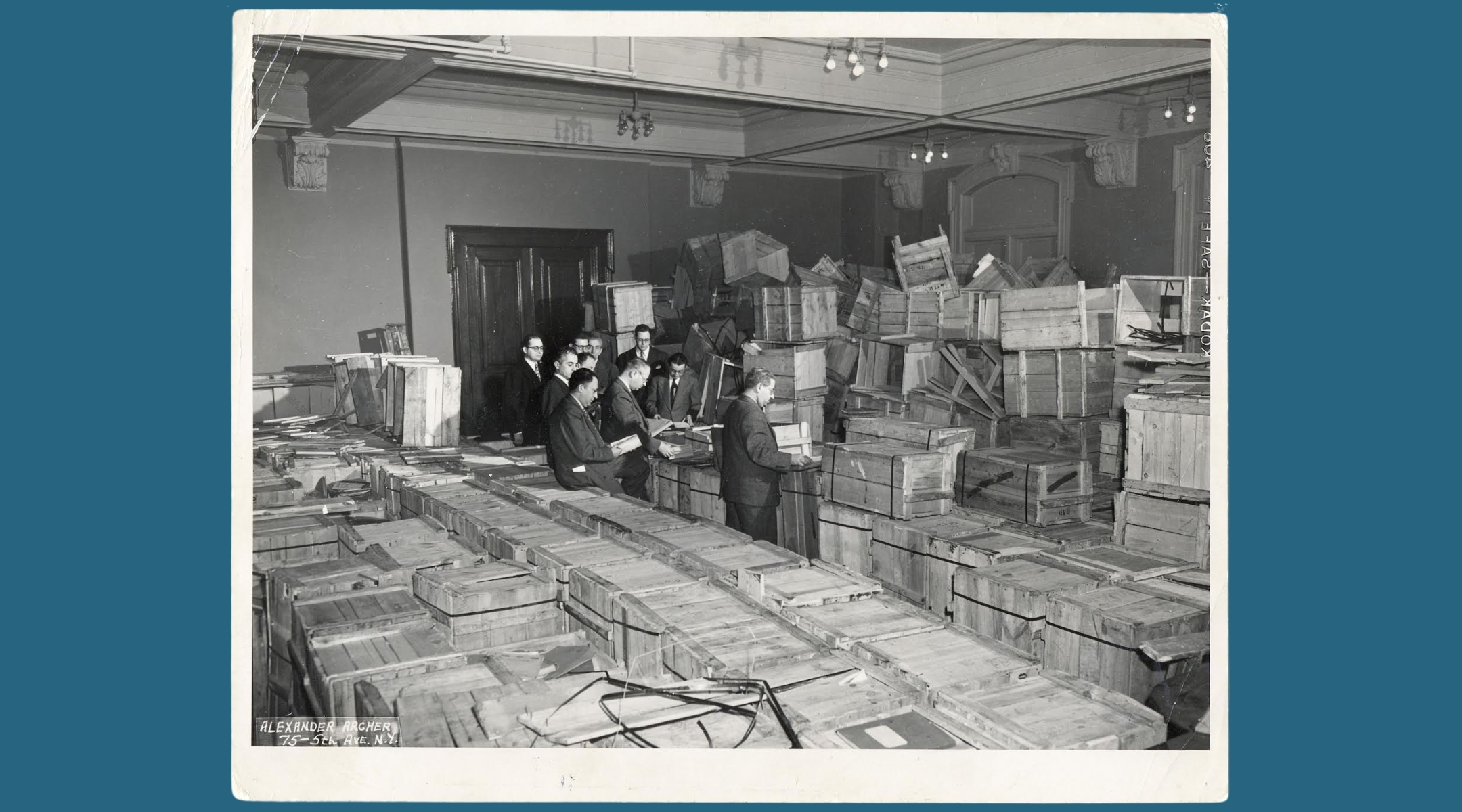

Leaders of the New York-based YIVO open crates of salvaged materials from Europe in 1947 at the Manischewitz matzah warehouse in New Jersey. (YIVO Institute of Jewish Research)

(New York Jewish Week) — In 1941, a group of intellectual Jews confined to the Vilna ghetto — writers, scholars, poets and the like — were forced by the Nazis to plunder their own people’s treasured works for a Nazi propaganda museum, the Institute for Research on the Jewish Question.

These intellectuals, including the poet Abraham Sutzkever and the writer and artist Shmerke Kaczerginski, were forced to pack away treasures like historic bibles and Jewish artwork, all bound for Nazi Germany. But their labors also included a secret act of resistance: Members of the “paper brigade,” as these Jews have come to be known, also methodically packed and hid from the Nazis some 465 crates filled with documents like periodicals, recordings and photographs, all intended to preserve the cultural heritage of the Jews of Eastern Europe.

Forced to loot local Jewish libraries and YIVO — the Yiddish acronym for Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut, or Yiddish Scientific Institute, an organization that had been founded in Vilna 16 years earlier — other paper brigaders managed to hide Jewish documents under their clothing and sneak them back into the Vilna Ghetto. There, they buried them deep in the ground, where they hoped to find them if and when the war ended.

YIVO was born on March 24, 1925, at a time of rising nationalism and increased antisemitism in Europe. Created to document Eastern European Jewish life and to study Yiddish language and culture, the organization played an instrumental role during the Holocaust; its members and affiliates hid thousands of Jewish documents and manuscripts from destruction by the Nazis.

Eventually, the secreted-away materials made their way to the New York office of YIVO (with a brief stint at the Manischewitz matzah warehouse in New Jersey), which opened in the mid-1930s in Morningside Heights, across from the Jewish Theological Seminary. The institution later moved to the Upper East Side before landing at its current location, at the Center for Jewish History on West 16th Street, in 2000.

YIVO’s satellite office in New York became their official headquarters in 1940, when the main office in Vilna was taken over by the Soviets and then the Nazis. YIVO’s Warsaw office was forced to close as the ghetto was formed in 1940, while their Berlin office was forced to close in 1933.

Today, as YIVO celebrates its 100th anniversary, it’s a multi-pronged New York cultural institution that presents a wide array of exhibitions, cultural events, Yiddish language classes and lectures. It also, of course, boasts a massive collection of art, artifacts, manuscripts, books and recordings — YIVO’s archive is comprised of some 24 million documents, 400,000 books and 250,000 photos.

Incredibly, while YIVO is embarking on a multi-year project to digitize their archive, their holdings are open to any New Yorker or visitor who’d like to peruse the collection. All anyone has to do is make an appointment, and an archivist will bring them out to you for a closer look.

As this reporter can attest, there’s something special that happens when you’re in the presence of an artifact that was passed down through generations of one family, or that might be the only remaining evidence that a person existed.

In honor of YIVO’s centennial, keep scrolling to see seven treasures from the YIVO Archives. Read all about them here, or contact YIVO to see them for yourself.

The Rothschild family’s handwritten Tractate Bava Kamma, 1722

Amschel Moses Rothschild was born in 1710 in the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt. As a bar mitzvah student, Rothschild, likely in an effort to enhance his scribal ability and to commit the text to memory, hand wrote this tractate from the Bava Kamma, the first of three Talmudic tractates, which deals with Jewish civil law.

Rothschild grew up to be a money changer and he operated a modest silk trade business. He was also the father of Mayer Amschel Rothschild, the founder of the Rothschild banking dynasty.

This miniscule book was passed down to the men in the Rothschild family for nearly a century. There were some additions by its later owners, including a title page by Jonas Rothschild in 1795, which says: “Written by the hands of my grandfather, his honor, Reb. Amschel Rothschild of blessed memory, and passed into my hands by my master, my father, my teacher, his honor, the late Reb. Moses Rothschild of blessed memory in the year [5]555, Jonas Rothschild.”

Listen to a YIVO lecture about the artifact here.

A handmade Hanukkah menorah, 1872

This wood and cast tin menorah was crafted by a teen living in Myślenice, Galicia (near Kraków) named Khaim Aryeh Seifter for his bar mitzvah in 1872.

Seifter grew up to become a Torah scholar who also worked as a cantor, mohel and shochet, or ritual slaughterer. When Seifter’s son, Jacob, immigrated to the United States in 1905, Seifter gifted him the menorah, knowing he was unlikely to see him again. Seifter was killed in Auschwitz in 1942.

When, in the 1940s, YIVO attempted to put together a “Museum of the Homes of the Past,” and put out a call for items, Jacob Seifter sent his father’s handmade menorah. It has remained with YIVO ever since, becoming part of its permanent collection of materials.

“An item like this is a completely unique, very special piece of Judaica that doesn’t exist anywhere else,” said Eddy Portnoy, director of exhibitions at YIVO.

A first edition of “Der Judenstaat” by Theodor Herzl, 1896

“Der Judenstaat,” or “The Jewish State,” published in German in 1896 by Jewish writer and political activist Theodor Herzl, called for the creation of a national Jewish homeland.

Herzl went on to be known as the father of modern Zionism, although the term was not his invention. Rather, Nathan Birnbaum, an Austrian Jewish writer and peer of Herzl’s, coined the word Zionism — though Birnbaum later abandoned the Zionist cause and became a Yiddishist and, eventually ultra-Orthodox, becoming an instrumental part in founding the Agudat Yisrael Haredi political party in Israel in the 1910s.

Notably, this first edition of the book is dedicated by Herzl to Birnbaum.

A handwritten letter from Sigmund Freud, 1939

There are many personal letters in YIVO’s collection — and some of those belonged to or were sent from very important Jews.

Among them is a letter written by the Jewish father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, dated Jan. 21, 1939. Sent from his London home, where he lived after the Nazi takeover of Austria, Freud penned the letter in German “fraktur-style” handwriting, which is no longer in common use.

Addressed to Samuel Stendig, a publisher and writer in Kraków, this letter is a response to Stendig’s earlier request for Freud to submit an entry on his own work for a Polish Jewish encyclopedia, in an effort to improve the public perception of the Jewish people. In the letter, Freud acknowledges his failing health — he would die by assisted suicide with morphine due to painful jaw cancer later that year — and mentions that he does not have photos to submit because they were destroyed in Vienna.

YIVO has several connections with Freud: The institute’s first director, Max Weinreich, translated Freud’s “Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis” into Yiddish.

In addition, Freud wrote a letter in support of YIVO’s work in 1938. “We, Jews, have always known how to respect spiritual values. We preserved our unity through ideas, and because of them we have survived to this day,” Freud wrote. “The fact that Rabbi Jochanan ben Zakkai immediately after the destruction of the Temple obtained from the conqueror permission to establish the first academy forJewish knowledge in Jabneh [Yavneh] was for me always one of the most significant manifestations in our history.”

A book filled with signatures of Jewish students in the Łódź Ghetto, 1941

This book, filled with signatures of the 14,000 Jewish children who lived in the Łódź Ghetto, was given to Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the chair of the Judenrat, or Nazi-appointed Jewish council, of the ghetto.

The signature book was a gift for Rosh Hashanah in 1941. “They wanted to thank Rumkowski for opening the schools in the Łódź ghetto and providing meals,” according to YIVO. “Sadly, the same afternoon the album was given to Rumkowski, he learned that he would have to close the schools due to the increased housing needs of incoming deportees.”

The majority of the children who signed their names in the album were sent to Chełmno, the Nazi death camp just outside Vilna. Of the 14,000 names, only about 200 children survived the Holocaust.

A portrait of Austrian Nazi leader Arthur Seyss-Inquart, painted on segment of Torah scroll, 1940s

This oil painting of Austrian Nazi leader Arthur Seyss-Inquart — who was responsible for the deportation of Dutch Jews, and was tried and executed for war crimes at Nuremberg in October, 1946 — was created on a segment of a Torah scroll. Portnoy speculates that it was painted by force by a Jew.

“We don’t actually know who did it, but the whole purpose of it was that it was painted on a Torah scroll,” Portnoy said. “And this was just another way that the Nazis humiliated the Jews by taking their holiest documents, their holiest texts, and just turning them into paintings of Nazis. I mean, it’s horrifying. The whole point was just that it was on a Torah scroll.”

There is value in collecting “antisemitica,” Portnoy said. Researchers can learn from it, and the Holocaust is a popular subject for scholars coming into the reading room.

“Different people want to see all kinds of different things,” he said.

A hand-annotated original manuscript of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “The Spinoza of Market Street,” 1940s

This Yiddish, typewritten manuscript of “The Spinoza of Market Street” includes handwritten edits from Nobel Prize-winning writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, considered one of the great Yiddish writers of the 20th century.

This is the original manuscript of the short story, about Dr. Nahum Fischelson, an elderly man living in Warsaw just days before the onset of World War I, who for 30 years studied “Ethics,” the 17th-century work by the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza. “The Spinoza of Market Street” was published in Yiddish in 1944 in the Yiddish literary magazine Di Tsukunft (The Future) and in English in 1961 in an anthology of Singer’s works.

Edits on the page contain Singer’s edits, and those of another editor, possibly Abraham Liessen, the editor of Di Tsukunft.

As a young man, Singer emigrated from Poland to New York City in 1935. He lived for most of his adult life in an apartment at the historic Belnord apartment building on the Upper West Side. West 86th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam is co-named after him.