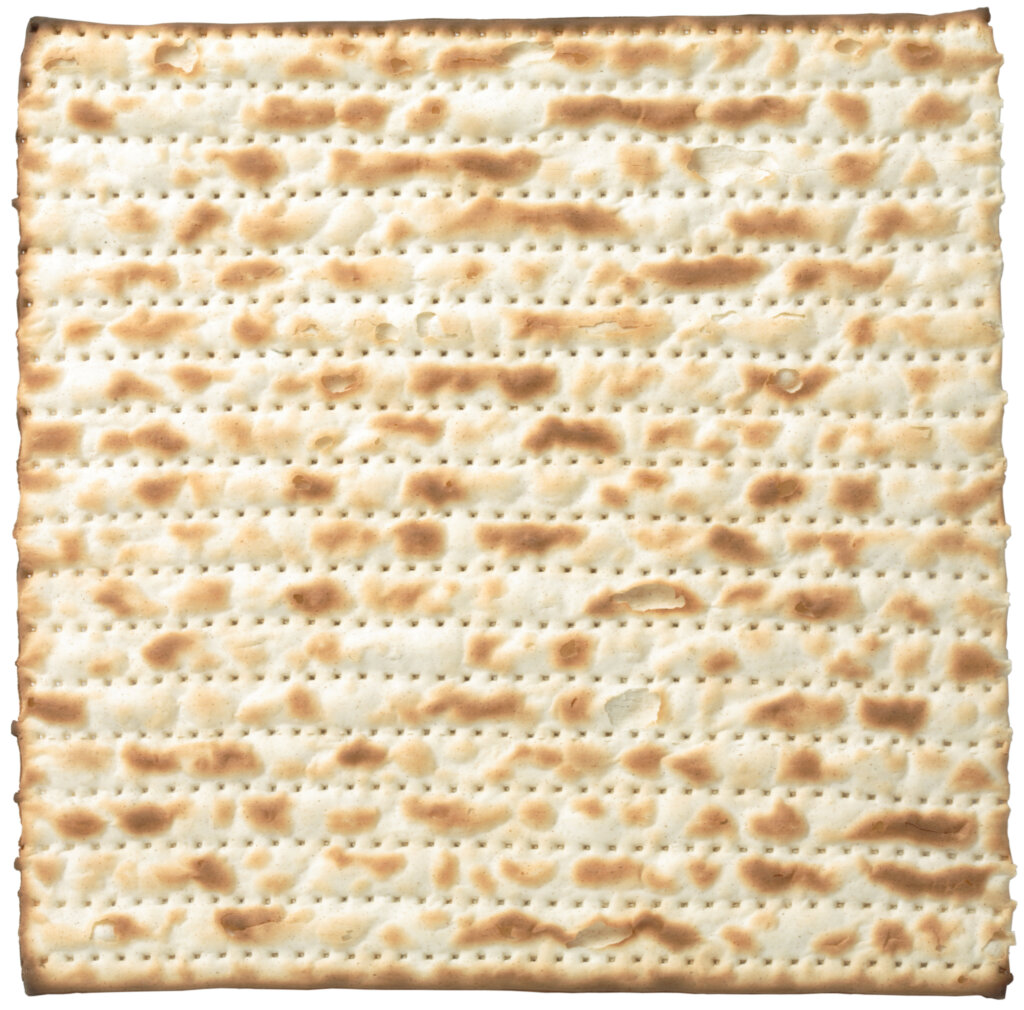

Soft matzo was once the norm throughout the Jewish world. Photo by Sam Lin-Sommer

I look forward to Passover every Spring. It’s a raucous affair of wine, food and storytelling, and I can’t get enough of it. But there’s one Passover item that I’m happy to do without: the dry slab of unsalted saltine cracker that we call “matzo.”

I look forward to Passover every Spring. It’s a raucous affair of wine, food and storytelling, and I can’t get enough of it. But there’s one Passover item that I’m happy to do without: the dry slab of unsalted saltine cracker that we call “matzo.”

At the Seders that I’ve been to, the bread of affliction has, at best, been a rustic, charred, oblong shmurah matzo, and, at worst, a mass-produced, desiccated square. In either case, we’re talking about a glorified cracker.

Does matzo really have to be this way?

It doesn’t. It turns out that I just needed to think outside the Ashkenormative box to see the truth.

A little inquiry revealed that many Mizrahi and Sephardic Jews enjoy a soft, pita-like matzo every Passover. Ethiopian Jews usher in the holiday with kit’ta, a soft matzo fried with sesame oil in a flat pan. Yemeni Jews traditionally bake a moist dough in a tandoor-like tabun to produce a soft, charred flatbread scattered with bubbles.

Libyan Jews often made a soft matzo before many of them migrated to Israel in the 20th century. In a paper on the history of matzo, baker-historians Ari Z Zitovsky and Ari Greenspan mention a conversation with a Libyan Israeli who recounted that his grandmother had not seen hard matzo until British troops brought it to Tripoli; she assumed that the brittle cracker was an army ration.

The recipe for soft matzo isn’t that different from the hard kind, but it often involves a higher water to flour ratio than its crunchy counterpart. In both cases, bakers mix, knead, and bake the dough in under 18 minutes to prevent the bread from rising.

A millenia-old tradition

It’s impossible to know whether the earliest matzos were soft or hard, since there are no biblical references to matzo’s texture, nor archaeological findings of its original form. But after studying indirect biblical references and a 2,000-year-old letter in Egypt, journalist Elon Gilad, author of The Secret History of Judaism, hypothesized that the earliest matzos were likely flat and crispy, not unlike the version that I detest today, but made of barley, not wheat.

Even if that is true, later halachic texts point to an unleavened bread that was eventually much thicker and softer than the modern-day Ashkenazi bread of affliction. Rabbi Anthony Manning wrote a memo for Jerusalem’s OU Israel Center drawing from texts spanning multiple traditions over some 1800 years to demonstrate that soft, thick matzo was likely the norm for much of Jewish history.

In the Talmud, composed of writings from the first five centuries C.E., rabbis dispute the optimal thickness of matzo, but even the most stringent rabbis say that matzo should be less than one tefach — about eight to nine centimeters — thick.

In the Shulchan Aruch, a legal code first published in 1565 that is still viewed as one of Judaism’s guiding texts, the Sephardic scholar Joseph Karo writes that a matzo is done baking when it can be pulled apart without threads of dough sticking to the tearer’s fingers. Have you ever tried to rip apart a piece of hard matzo? Good luck.

And in the Mishna Berura, a text written in the late 1800s, an Ashkenazi scholar tells bakers to test a matzo for doneness by sticking their finger into the bread and seeing if it comes out dry. In response, the 20th century Orthodox rabbi Chazon Ish noted that hard matzo dough is so dry that even raw dough wouldn’t leave moisture on a tester’s finger. Therefore, it’s likely that the 19th century Ashkenazi matzo was moist and chewy.

These passages, along with other close readings of matzo liturgy, have led scholars like Manning to believe that, for much of matzo’s history, it has been thicker and softer than the stuff on many American supermarket shelves.

Manning and the baker-historians Zitovsky, and Greenspan all believe that matzo thinned and dried out for a couple of main reasons. First, rabbis urged bakers to make matzo before Passover so that any baking mistakes would occur before the actual chametz prohibition began, and hard matzo keeps better than its softer cousin. Later, rabbis called for matzo to be made thinner out of concerns that the center of thicker matzo might remain uncooked and, thus, classify as chametz.

All of this has created a world in which the norm for many American Jews is to eat an unleavened cracker that shatters in our hands at the first bite. Ashkenazi rabbis still debate the merits of soft matzo, but it’s more common in the Sephardic world, and remains a staple of Yemeni and Ethiopian passovers.

Soft matzo in Brooklyn

I was pleased to learn that a viable alternative to my least favorite Passover dish existed. I didn’t expect just how easy it would be for me to get my hands on some.

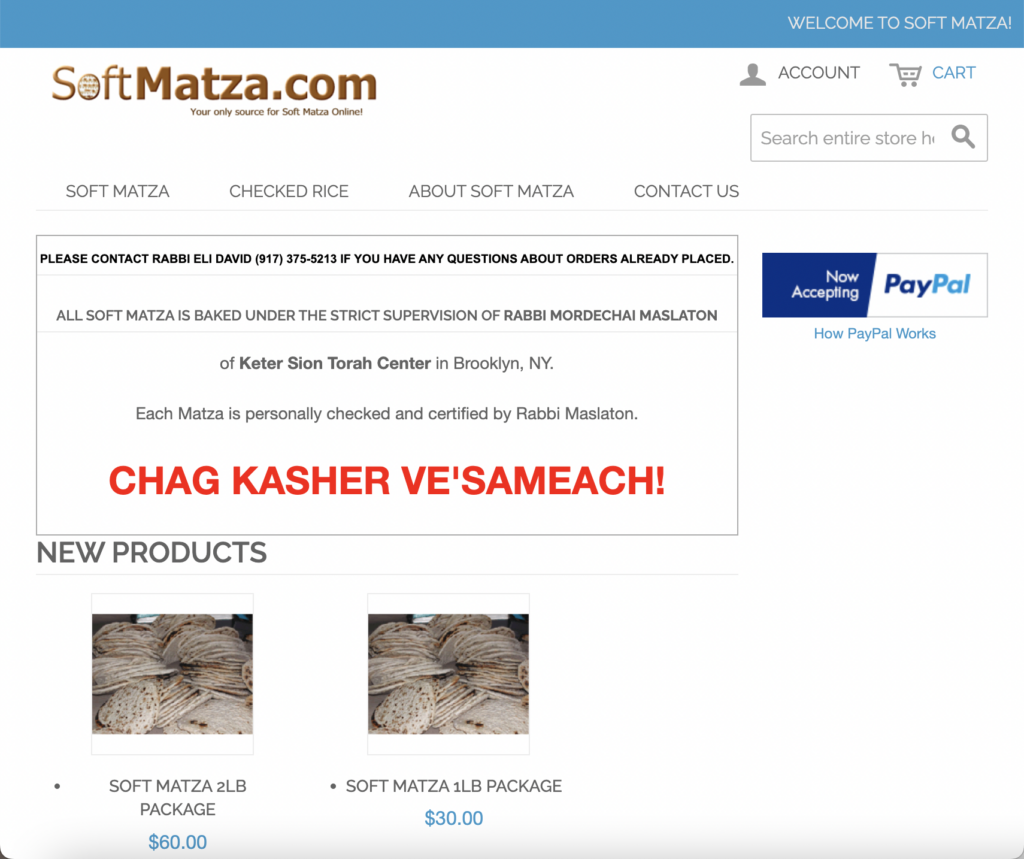

When I googled “soft matzo,” one of the first search results was a website titled “softmatza.com.” The page calls itself “Your only source for Soft Matza Online!” and offers soft shmurah matzo — Kosher-for-Passover matzo whose ingredients are monitored closely from harvest to baking — ready for pickup in Flatbush, Brooklyn, a stone’s throw from where I live.

Shlomo David, the son of the rabbi who bakes the matzo, told me that the soft matzo was part of a Sephardic Syrian tradition. Rabbi Eli David, bakes the matzo under the supervision of his father — Shlomo’s grandfather — Rabbi M. Maslaton, of Keter Sion Torah Center. Rabbi David makes the flatbread in a commercial bakery in Boro Park.

“In general, people of Sephardic lineage have a minhag (tradition) to eat soft matzot on Passover,” the soft matzo website reads. “People from Ashkenazic lineage have a minhag (tradition) to eat Matza that is as thin as possible, and therefore should consult their Rabbi to determine if they are allowed to our thicker Matza.” I’m sorry to say that I’m yet to consult my rabbi on this one.

I did chat briefly with Rabbi Eli, who directed me to a young man who was working for him to place an order. I ended up in a quiet stretch of South Brooklyn in front of a shingled house with a few trees. I waited outside until the rabbi’s helper, a boy who looked like he was a teenager and wore a black suit and yarmulke, glided over in an electric scooter with a plastic bag of the good stuff in one hand.

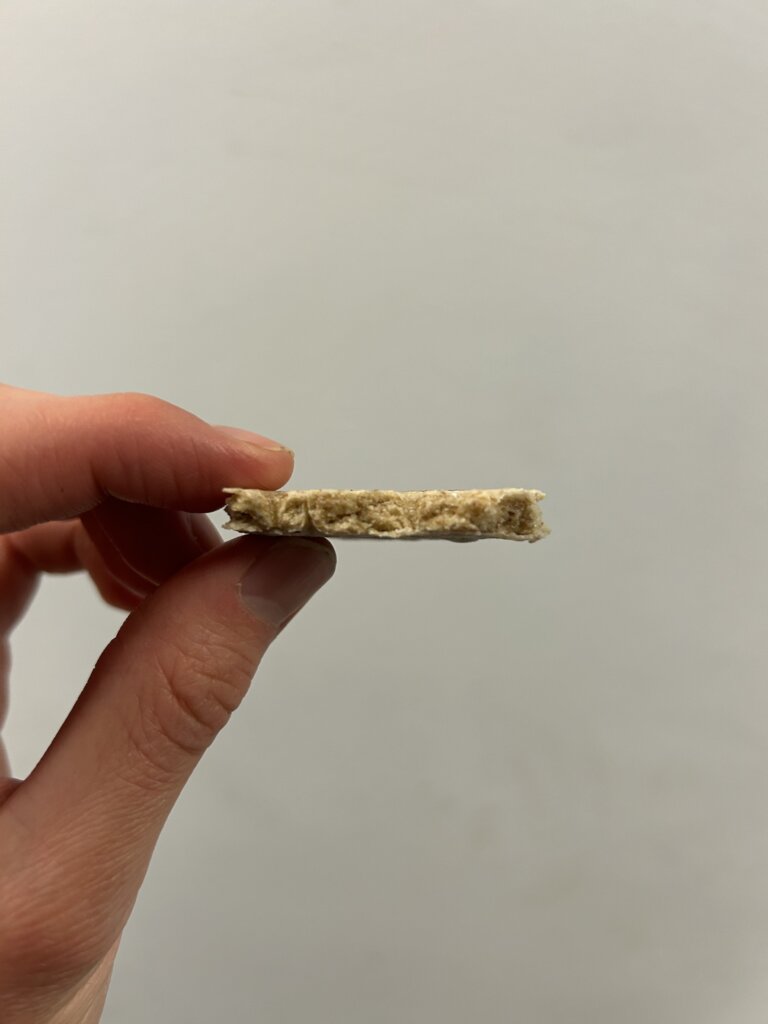

I bought four dense flatbreads, weighing about a pound, for $30; soft shmurah matzo, like the dry variety, is expensive. These were cold, as if they had just been plucked from the freezer. The tan disks were dotted with holes and char marks, and very flat.

I brought them home for a pre-Passover tasting. Since soft matzo can go stale (whereas hard matzo is, let’s face it, always stale), the package’s label says to keep them frozen until ready to serve. When it’s time to eat them, just thaw them for two hours, then heat them in an oven for another two minutes.

I invited my cousin to join me, and we took bites of a warm matzo. The bread was dense — it lacked the air bubbles of a leavened pita — and resembled a thin, chewy cake as much as a flatbread. I preferred the moist chewiness of this matzo to the desert-like dryness of the Manischewitz kind — though in taste, it was pretty similar to the crispy crackers I was used to: pure, unsalted wheat.

This chewy, earthy, variation would be nice, I imagine, wrapped around a Syrian charoset studded with nuts and dates, or dipped in saltah, the Yemeni Passover stew made with meat, fenugreek, chilies, and tomatoes.

But these Flatbush flatbreads are one of countless variations on a bread that was likely once the standard for global Jewry, and is still the norm in many communities. And compared to the reheated ones that I tried, traditional soft matzot will probably taste more delicious for being consumed the classic way: fresh out of the oven.

I’ll admit that I didn’t enjoy the matzo now sitting in my freezer as much as I would, say, a pita or a naan bread. That may be because it’s reheated, because I tried it plain rather than alongside a delicious Sephardic or Mizrahi dish or simply because I don’t have a highly developed flatbread palette.

But perhaps I’m not meant to enjoy these unleavened disks as much as a fluffy pita. Matzo is supposed to be the “bread of affliction,” after all — this version is just a little less afflicted.