Are Jews afraid of Christmas?

Learn why shtetl Jews covered their pots on Christmas Eve and other fascinating traditions related to the holiday

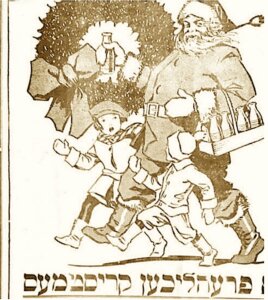

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

We all know about the American Jewish tradition of dining out in Chinese restaurants on Christmas Eve. It’s a sign that American Jews have always enjoyed themselves that night, alongside their fellow Americans, albeit not quite in the same way.

When Jewish immigrants came to America, they quickly adopted Christmas as an American holiday, distinct from its Christian context. In the 1920s, even the religiously traditional New York Yiddish newspaper, the Morgn-Zhurnal, would print pages full of Christmas greetings from local businesses in Yiddish. They often wished readers “a freylekhn Christmas,” a happy Christmas.

Yiddish writers criticized American Jews’ positive attitude to Christmas

More recent immigrants, among them Yiddish writers, condemned this practice. Literary critic Shmuel Charney explained that when Jews in his hometown of Dukora, Belarus, would hear the church bells before Christmas, they understood it as a veiled warning: “Go home, be quiet! You mustn’t be on the street now for any reason.” Many Jewish Christmas traditions in the Old Country were a way of expressing fear. But what exactly were they afraid of?

Older Jewish religious texts instructed all Jews to stay home on Christmas Eve because Christians might attack, or even kill them. Historically speaking, however, far more acts of violence were committed against Jews during Easter. Christians mark this holiday as the day Jesus died, in contrast with Christmas when they celebrate his birth.

Pogroms would also break out on the 40th day of the Easter holiday season, the day when Christians believe that Jesus ascended to heaven. Springtime generally saw more attacks against Jews than December as the weather was warmer and the ground wasn’t covered in snow.

Traditional Jewish beliefs about the Christian deity

Over the centuries, these dangers generated a substantial folklore. Jews believed that on Christmas Eve, the Christian deity flew around and controlled the night. If any Jew were to open a Jewish holy text that night, that spirit could appear at any time and defile the holy book. This tradition continues among Hasidic groups today who actually don’t study Torah on Christmas. Some even interpret the Yiddish word for Christmas, “nitl” as an abbreviation for “no studying” (nit lernen). Jews believed that doing anything related to Torah study on Christmas might be misinterpreted as honoring Jesus.

For generations, Jews spent Christmas Eve doing all sorts of things that couldn’t be misinterpreted as honoring Jesus. Some baked garlic bread due to its strong odor. Many played cards or dreidel. Lubavitcher Hasidim have a tradition of playing chess on Christmas Eve that continues to this day.

Jewish fear of the winter solstice

Jews also had fears and traditions surrounding the winter solstice, which falls a few days before Christmas. Scientifically speaking, the winter solstice is simply the longest night of the year. But Jews believed that on this night when the seasons changed, the Earth was left unprotected. An old tradition connected to the winter solstice was to cover all pots that held well water so that the water would not be contaminated. While some people, like my father, knew the tradition’s true origin, by modern times, the two traditions had gotten blurred. Jews began covering up their pots on Christmas Eve so that the Christian deity wouldn’t poison their well water while flying overhead.

The image of a “flying Jesus” comes from Sefer Toledos Yeshu, a parody on the life of Jesus that Jews apparently read on Christmas Eve for hundreds of years. At one point in the story, Jesus acquires the ability to fly through the air thanks to a tetragram of God’s name that he stole from the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and sewed into his leg. On the basis of this story, Jesus became a demon of sorts for the Jewish masses, who Jews believed flew around and caused great troubles for Jews.

This is, of course, a very different take on Christmas than what most American Jews have today. True, Jews no longer fear Christmas Eve, but many admit that this day still makes them feel like the odd man out.