Curator of ‘Living Yiddish in New York’ exhibit gives you a quick tour

The exhibit at the Jewish Theological Seminary includes materials on the history of New York’s Yiddish-speaking left

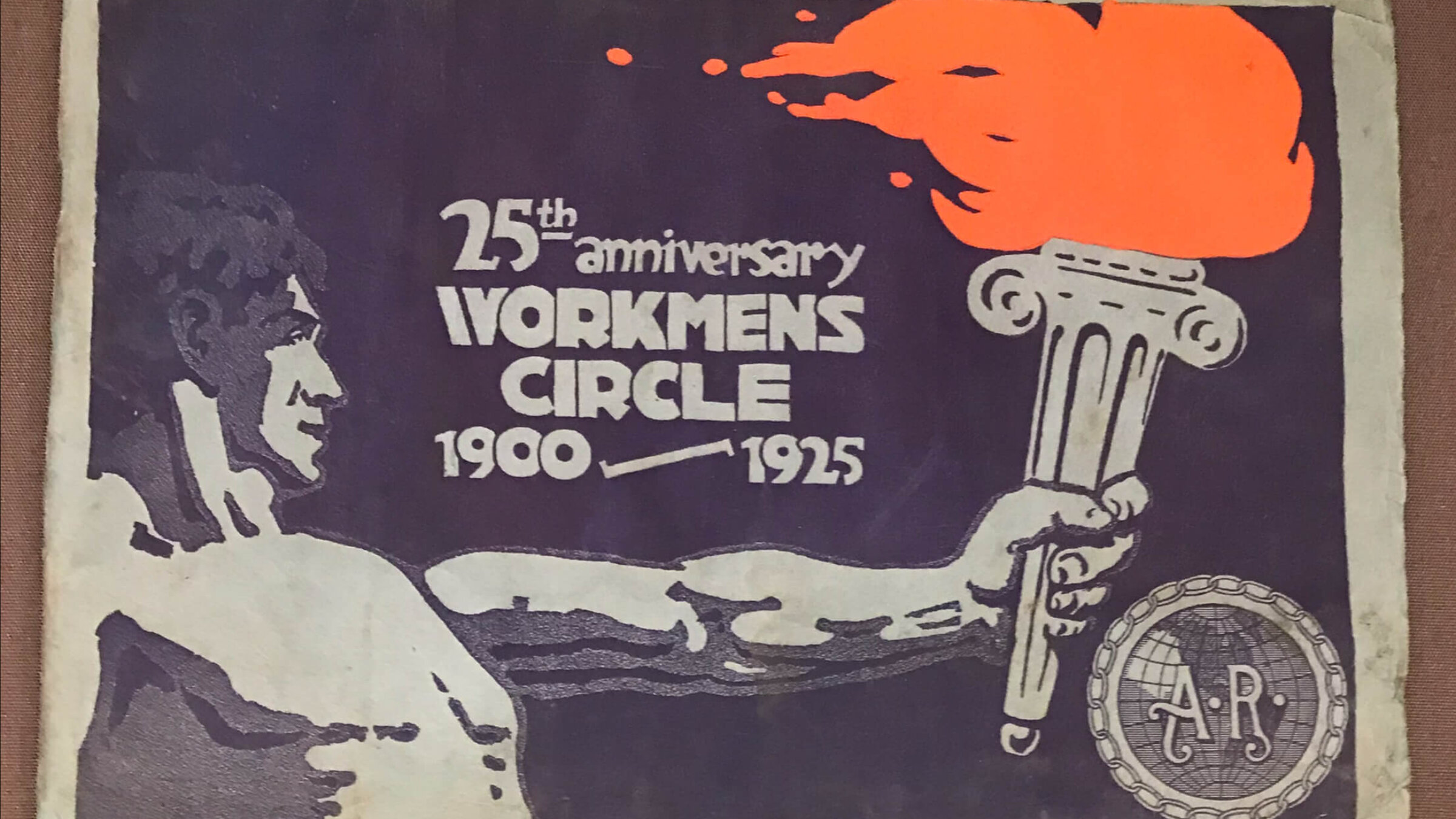

An almanac documenting everything the “Arbeter Ring” (Workmen’s Circle) had accomplished during its first 25 years (1925) Courtesy of the Jewish Theological Seminary

There are lots of reasons why someone like me — a graduate student from the U.K. — might want to come and study in New York City.

But for me, there was one big attraction: Yiddish. I started learning the language as an undergraduate at the University of London, to facilitate the research I wanted to do. But I quickly fell in love with it. As the grandchild of Jewish immigrants from Poland and Lithuania, learning Yiddish filled a gap in my Jewish experience and identity that I hadn’t fully realized was even there. Since then, I’ve dedicated far more time and energy to learning, speaking, creating and now teaching Yiddish than my research alone requires.

At the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), where I’m studying for my Ph.D. in modern Jewish history, I even talk to my supervisor, David Fishman, primarily in Yiddish. Last year, I was able to attend a graduate seminar on the history of modern Jewish culture that he taught entirely in Yiddish. This year, on his recommendation, I was offered an even more exciting opportunity: the chance to put together an exhibition for the JTS library, using their Yiddish archival collections to illustrate how New York became — and remains today — one of the capitals of “Yiddishland.”

The rise of the Yiddish-speaking left

The exhibition, Living Yiddish in New York, opened on April 20 at the JTS library. It begins with materials that document the huge waves of Eastern European Jewish immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and the organizations immigrants created to help them adapt and survive in the big city.

Many of the materials in the exhibition relate to the development of the Yiddish-speaking left. (The Jewish left is actually the focus of my doctorate). People often assume that socialist politics migrated to New York with the Jewish and Russian immigrants. But as historian Tony Michaels demonstrates in his book on the city’s Yiddish-speaking Socialists, the drift of Yiddish-speaking New Yorkers to the left can be better ascribed to the harsh living and working conditions they faced as new immigrants, as well as the work of Yiddish intellectuals like Forverts founder Abraham Cahan.

The development of the Yiddish left in New York was also facilitated by the freedoms Jews enjoyed here. Between the 1905 and 1917 Russian revolutions, when leftists in Russia experienced harsh persecution, New York was an important center from which the transnational Jewish left could agitate and organize. The contrast between the difficulties of life in New York and the relative freedom enjoyed by Jewish immigrants is something I and my co-curators tried to highlight in the exhibition. In New York, Jews were free to create and perform in ways that were still restricted in Russia.

Lots of Yiddish theater sheet music

By 1914, this creativity had turned the city into one of the world capitals of Yiddish culture. The Forverts, a copy of which is displayed alongside literary journals, sheet music and photographs from the Yiddish theater, was part of this. The longest-running Yiddish newspaper in history, it is also the biggest success story of what was the world’s first popular Yiddish newspaper market.

Meanwhile, New York’s Yiddish Theatre district — known as the Yiddish or Jewish “Rialto” — was the most successful in the world, hosting 20-30 shows a night. Examples of JTS’ vast collection of Yiddish sheet music from these shows, as well as some photos of a 1930s production of The Wise Men of Chelm, make up some of the most beautiful materials on display. However, as other exhibit materials demonstrate, for many Jewish immigrants, the Yiddish theater and cinema actually represented the decline of traditional Jewish life, culture and morality.

While the neon lights of the Yiddish Rialto may have disappeared from Second Avenue, New York remains one of the major centers of Yiddish culture. Curating this exhibition gave me the opportunity to engage with the story of how New York became what it is for me — a place where I can really “live” Yiddish. For me, one of the most important parts of the exhibition is the small section, “Fun dor tsu dor” (From generation to generation), which documents the efforts of Yiddish speakers to pass on their language and culture to their children. While this was in many ways a losing battle, the fact that I and many others still come to New York to study and enjoy Yiddish demonstrates that it was also a success story.

Why there are no Holocaust-related materials

Unsurprisingly, given the richness of Yiddish life in New York, one of the hardest decisions I and my co-curators had to make was which materials not to include. Particularly difficult was the decision to avoid materials relating to the Holocaust, which we decided was too big and emotional a topic to give only part of an already small exhibit. With many Yiddish centers in Europe decimated in the khurbn (the Yiddish word for Shoah), New York’s prominence as a Yiddish center after the war increased, with organizations like YIVO moving their headquarters to the city. Perhaps some of the materials I discovered in the research for this exhibit — posters advertising anti-fascist demonstrations, and some curious anti-Hitler poems — will form the focus of a future project.

When people ask me to identify the most exciting items on display, I automatically point to the leftist publications, in particular the rare items like the anarchist Frayhayt and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union’s Vanguard. Another goal of the exhibit is to begin to document the huge wealth of Yiddish materials available at JTS. As someone who spends many of my happiest hours in archives, it’s been a thrill to be part of this project and to discover how many materials relating to my own field of study were sitting under my feet, in the storage rooms of this institution.

This exhibition aims to paint a picture of Yiddish New York in all its nuances and contradictions. Living Yiddish in New York will be on display in the JTS library until Aug. 10, Monday-Thursday, 9 a.m.-7 p.m. or by appointment. Admission is free and guided tours are available.