My great-grandfather was not a rich man. But his last will and testament was full of riches.

Each death and each move is a moment to not just rediscover but re-curate our histories.

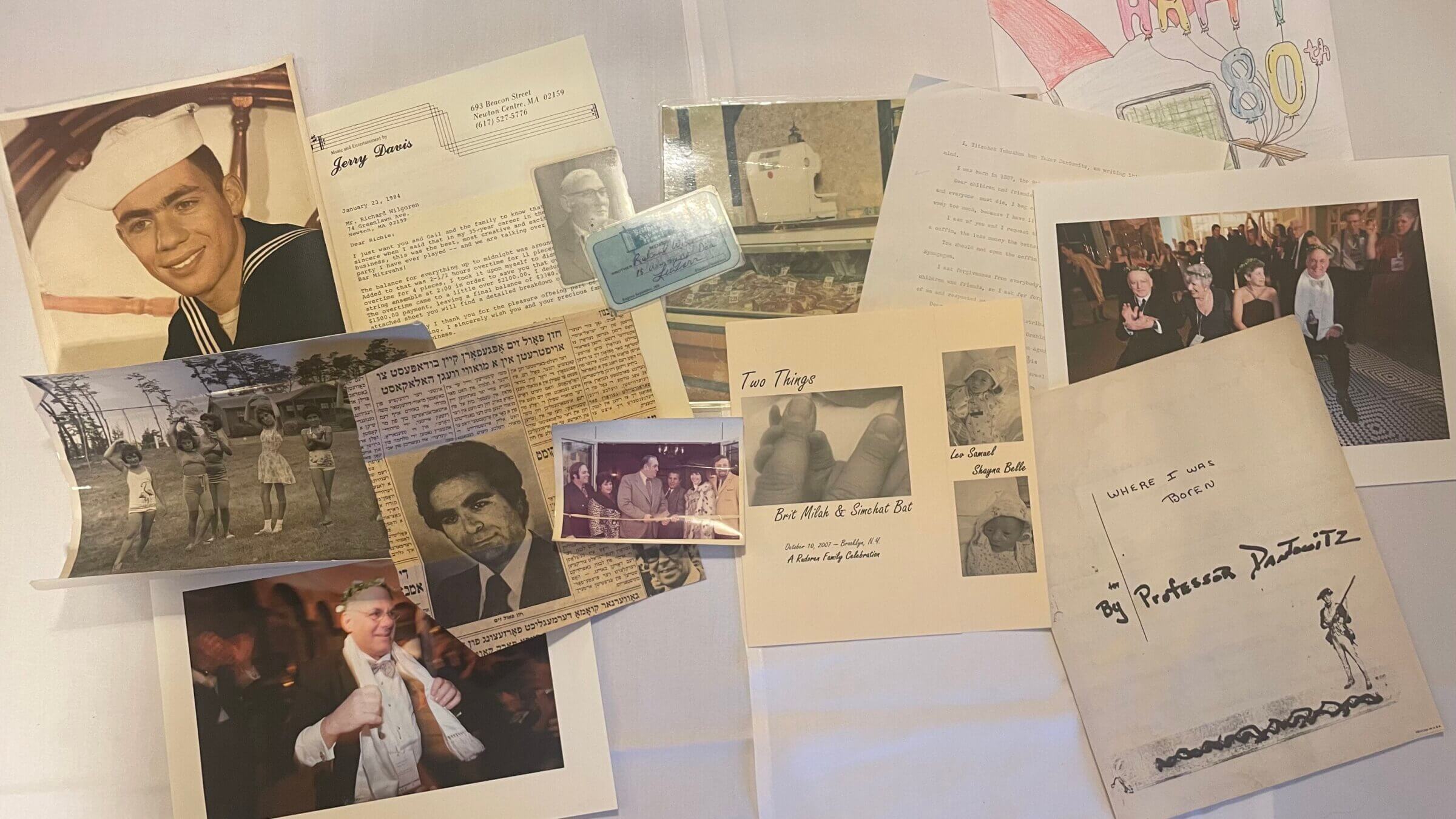

Some of the precious things I saved, including a colorized photo of my dad in the Coast Guard and a black-and-white of my mom as a girl at Camp Wingo (far left); the Jerry Davis Band bill from my 1983 bat mitzvah; a Yiddish newspaper clip about Cantor Paul Zim; photos from the opening of my dad’s butcher shop; the program from my kids’ baby naming; a portrait of my great-grandfather and a copy of his will. Photo by Jodi Rudoren

My great-grandfather’s will is a single page, 235 words typed on plain paper and signed in Yiddish. It is undated, but he died in 1967, of pancreatic cancer.

“Dear children and friends,” Zayde wrote, “when the time will come and I will die, and everyone must die, I beg of you, children and friends, you shall not weep too much, because I have lived a full life.”

His name was Yitzchok Yehoshua Dantowitz and he was born in 1887 in Ciechanów, Poland. He came to the U.S. in 1906, worked as a tailor in Boston, and taught my father — who later taught me — how to be a Jew. The will requests that “the less money the better” be spent on a coffin, and lists five communal charities to each receive $25 — worth $250 today.

“I ask forgiveness from everyone,” it says. “Maybe I did not do right by my children and friends, so I ask forgiveness. All of you took good care of me and respected me.”

Zayde’s humble, poetic, faded words were among the treasures we uncovered this week as we packed up the house where my parents lived for 36 years to move my mother into a Hebrew Senior Life community.

There was a black-and-white photo of a pouty Mom as a girl at Camp Wingo, and one of Dad in his Coast Guard uniform where his face looks remarkably like my nephew’s. The $3,380 bill the bandleader sent after my 1983 bat mitzvah that describes it as “the best, most creative and exciting” of the more than 7,000 coming-of-age parties he’d played in a 35-year-career. A Yiddish newspaper clip that seems to be from the Forward about my father’s lifelong friend, Cantor Paul Zim, going to Budapest to shoot a movie about the Holocaust.

My sisters and I were sorting through these mementos and a thrift store’s worth of kitchenware, books, art and ephemera two weeks after we completed the 11 months of reciting kaddish for Dad daily, two weeks before his first yahrzeit — and just ahead of the 100-day mark since the Hamas terror attack on Israel that sparked this devastating war in Gaza.

I am painfully aware of how lucky we are to have the luxury of choosing which tidbits of our history to hold close and which to give or throw away — unlike the Israeli kibbutzniks whose homes were torched on Oct. 7 and the Palestinians whose homes have been flattened by Israeli airstrikes since. To have been able to say proper, thought-out goodbyes to my father in his final days — unlike the thousands of families whose loved ones have been taken in an instant.

It feels terribly indulgent, then, to have spent the week torn over which of the myriad serving pieces my father used over decades of Jewish holiday entertaining, calculating how much I can possibly cram into the car and store in our New Jersey basement in case one of the grandkids wants it someday, crying as we reread old birthday cards and letters from camp.

And yet. It also feels important, somehow, to tell the story buried in these boxes. Not because it is a particularly significant or special story, but precisely because it’s not.

The longer something has been held onto, the harder it is to throw away. That’s why I already have in my basement crates filled with valentines I got in elementary school and journals I kept in junior high and papers I wrote in college. But each death and each move is a moment to not just rediscover but re-curate our histories.

As I sorted through the boxes, I tried to keep only the things I really wanted to show my own children, things I imagined they might someday want to show their future children.

The pictures of Dad and his partner Marty Rosenberg, who died decades ago, at the ribbon-cutting of their kosher butcher shop in Newton, Massachusetts. The mayor, Teddy Mann, was there, along with Mom and our lifelong friend Susan, Marty’s wife, in their chic 1970s fur coats.

The glowing college recommendation from my high school newspaper adviser. The program from my twins’ brit milah and baby naming. The faux front page I made about my family’s first trip to Israel in 1993. The 80th birthday card my daughter drew for my dad.

That bill from my bat mitzvah, which says the party lasted past 2 a.m., and that newspaper clip about Cantor Zim, who by the way sang “Yiddishe Mama” to my grandmothers at that epic party. The film he flew to Budapest for was War and Love (1985), which told the story of Jacek Eisner and other Jewish kids who survived the Warsaw ghetto.

Zim played the famous cantor and lyric tenor Moshe Koussevitzky, a special honor since it was Koussevitzky who taught Zim how to lead services, which Zim is still doing, in his 80s, as cantor of Congregation Gesher Shalom in Fort Lee, N.J.

“I probably would never have visited Budapest, but the Danube River was beautiful to see, and to film the movie in a synagogue, a historical house of worship, made the trip more appealing,” Zim texted me after I sent him a picture of the old Yiddish clipping the other day. “Part of my fee was to train teenagers from the Khodahy School, all non-Jewish but they were supernal. One 16-year-old sang a prayer that I used to sing at weddings in NYC, and it was something that Eisner sang as a child in Warsaw.”

The actor Tony Curtis and the makeup mogul Estee Lauder gave $20 million to restore that synagogue on Budapest’s Dohány Street.

“Unfortunately, the movie did not get good reviews,” Zim said. “But for me, it was a true memorable experience.”

Then there are the prolific broken-English writings of my great-grandfather’s brother, Israel Dantowitz — we called him Uncle Srul — chronicling various family simchas, holidays and individual life stories.

“I remember a lot of things from my childhood,” reads one titled All Our Love and dated 1974. “We was very happy when we were young children. When Saturday came we sitting together by the Shabos table with our father and mother and celebrate the Shabos.”

Of my great-grandfather, who Uncle Srul called Yeshie: “He came to Boston, he started working on men’s pants, he got a shop in Boston. He was doing very good. Then he got married. He also was writing good letters home.”

I was named after Yeshie — Yitzchok Yehoshua, as the will is signed, Isaac Joshua in English. The way my dad told the story is that he’d hoped to have a boy to carry his zayde’s exact name, but that after I was born, the third of three girls, my mom said she was done, and so he had to improvise. “Jodi” instead of “Joshua” made enough sense, but the Hebrew name required a little more improvisation.

Dad said he asked his rabbi for help, and the rabbi asked if Zayde had a nickname. “Shi’ah,” Dad said, a kind of slurred Yiddish version of Yehoshua. And so I got the Hebrew name Shira, which means song.

Maybe that’s why finding Zayde’s will made me cry. Like my Dad, who told us as he entered hospice care last February not only where his funeral should be but at what time, Yitzchok Yehoshua gave his survivors specific instructions.

“I ask that a proper kosher Taharah be made for me,” he wrote, referring to the Jewish ritual cleansing of a dead body. “You should not open the coffin and they shall not take me into the synagogue.”

He was not a man of means. The five charities he designated to receive $25 each were his synagogue, Congregation Agudath Israel, its Hebrew school, two local cemeteries and an outfit devoted to the mitzvah of welcoming guests. The only other inheritance he specified were his talit and tefillin — one set went to my dad, and now belongs to my brother-in-law, the other to my dad’s Uncle Sam, who Zayde called by his Hebrew and Yiddish name, Simcha.

“My dear son Simcha, I ask of you that what remains you shall divide with everybody equally,” reads the last paragraph. “Be well, and may you live as long as I have lived.”

Amen.