Learning to Love Christmas, Eggnog and All

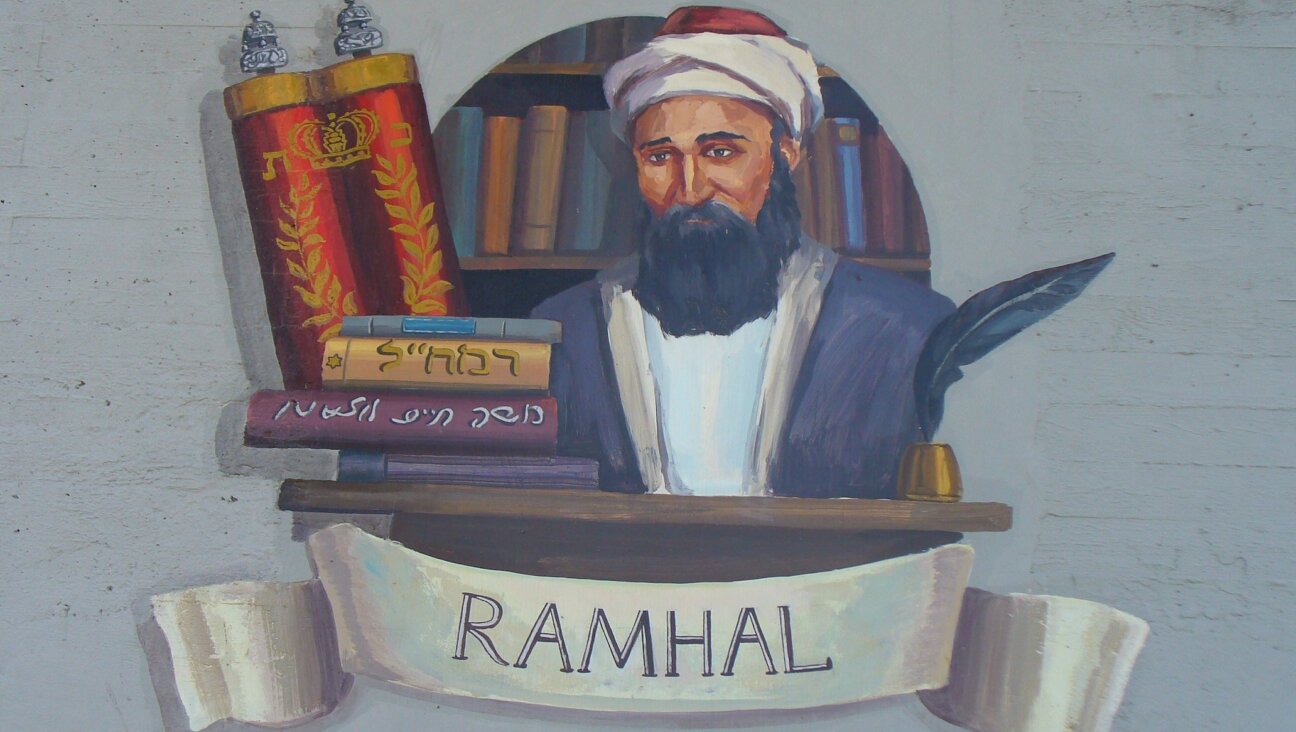

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Photograph via Flickr/Creative Commons

As an Orthodox Jew who believes in the world to come while participating pretty fully in the world at large, I will admit that there are certain things I like about Christmas aka “the holiday season.” I like the festive spirit, the Starbucks sweet and spicy Christmas blend coffee, and the colorful lights illuminating the short, dark December days.

Most of all, I appreciate that, at this time of year, people feel called on to practice random or even willful acts of kindness and generosity such as donating money and toys to the needy or allowing someone with fewer items to go ahead of them in the supermarket.

Yet I didn’t always feel this way. As a Jewy little girl Jewish girl growing up in less-than-Jewy Wilmington, Delaware, I wasn’t very happy with Christmas. I dreaded having strangers on city buses ask me what I wanted Santa to bring me, I was embarrassed that we were one of only two houses on the block with a wreathless door, but most of all, I hated having to stand up in front of my non-Jewish elementary school classmates and talk about Chanukah.

How could our waxy-candled menorahs and our measly little chocolate gelt and dreidels, compare with their large evergreens, lawn reindeers, and big, important gifts?

And then there was the Christmas carol conundrum. I liked the songs but didn’t know if I was allowed to. I especially loved “O Holy Night,” which I first heard sung by our elementary school Glee Club at a Christmas assembly.

The piano crescendo at the beginning, which sounded like rolling ocean waves, in combination with the sweet high voices of the girls in fifth grade and their dramatic injunction to “fall on your knees,” transported me in the same way that listening to certain Israeli folk songs like, “Ma Yafim Ha Leylot” did.

Yes, “O Holy” was a seriously Christian hymn, but Miss Goldstein, the school’s very Jewish music teacher and choir conductor had chosen to include the song—so how bad could it be?

I still wasn’t sure, nor about whether or not to sing all the words to “O Come All Ye Faithful” while standing around the ornament-laden tree in the school lobby. Only much later did I discover my father had felt the same way when he was in school, worrying about his Russian-Jewish mother’s reaction to his singing carols, and substituting the words at the end of “O Come All Ye Faithful” with “rice, the gourd.”

So, throughout my childhood and into adolescence, I felt guilty, self-conscious, and often assaulted by the blinking red and green lights, the tinsel, and the relentless holiday cheer. But my way of dealing as I got older was to follow the lead of other members of my tribe and turn my discomfort into telling cheesy Christmas vs. Chanukah jokes and singing Alan Sherman parodies of Christmas carols. It made me feel both more Jewish and less American. It wasn’t until several decades later, after I became traditionally observant, and my children were ensconced in Jewish day schools, that my feeling about Christmas began to shift. It may have had to do initially with a feeling of relief. After having prepared multiple meals for large groups during Rosh Hashanah, Sukkot, and then Thanksgiving (which we celebrate devoutly), I began to look forward to some “down time” at Christmas. Here was a holiday for which I had no ritual or culinary obligation, other than possibly going to the movies and eating kosher Chinese food. I could sit back, relax, have coffee with eggnog with my Catholic friend Susan on the morning of December 25th, and chuckle as I listened to her CD of Minnesota Jew Bob Dylan singing, among other carols, “O Come All Ye Faithful.” Christmas became a day of rest, like Shabbat, but without all the praying.

And then, several years later, after interviewing more than a dozen Jewish American WWII vets, my feelings about Christmas became even less ambivalent. In talking to men who had refused to wallow in victimhood during their service and who had no conflict between their Jewish and American identities, I realized that I had no longer had either the standing or the desire to feel so besieged by the omnipresence of Christmas on my street, my neighborhood, or in my workplace.

So I stopped whining, started collecting money for the office holiday party (although I wouldn’t touch the meat and cheese platters) and sometimes even brought in a $10 Starbucks gift card for the gift exchange. And soon enough, I came to not only embrace my participation at the party along with my Russian, Indian, Chinese, and Vietnamese coworkers—but to see how lucky I was and am to be a Jewish American, even and maybe especially at this time of year. I can have my own holidays and my eggnog, too.