While American Orthodox Feminists Fight for Clergy Recognition, Israeli Feminists Revolutionize Israel

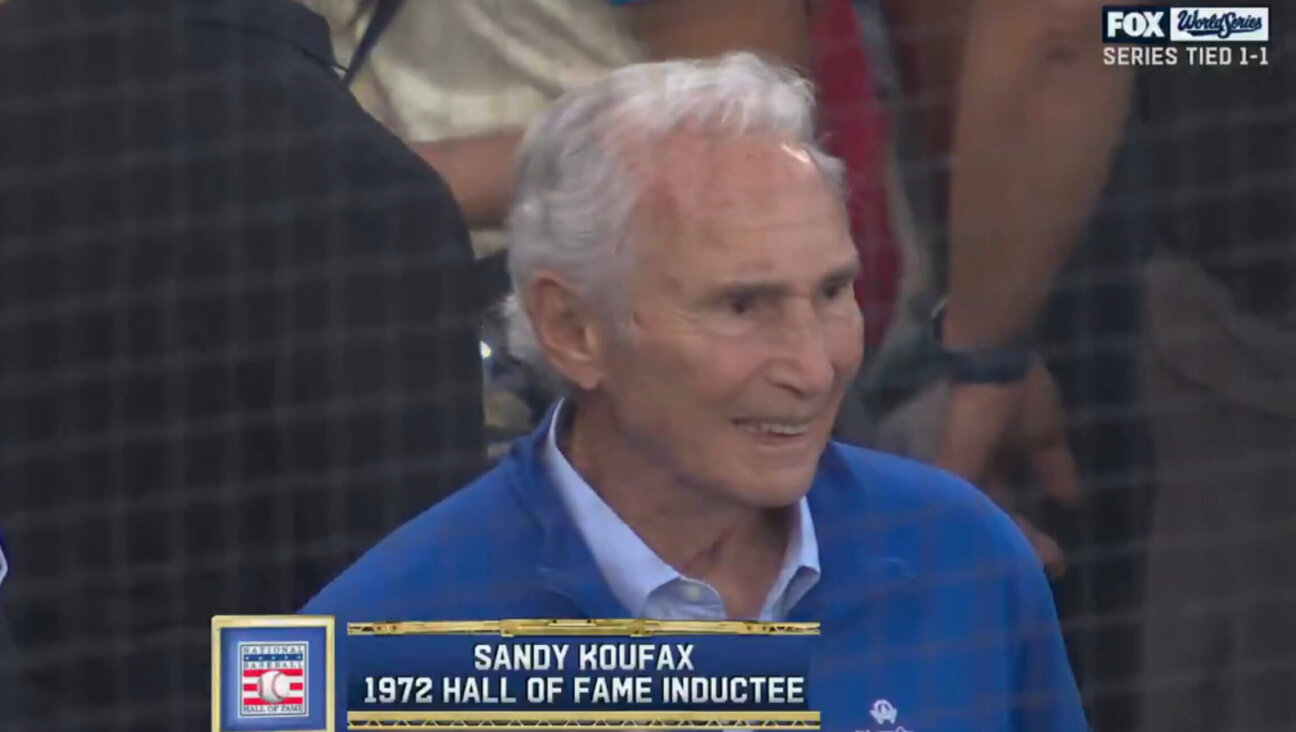

Image by Courtesy of Kolech/Facebook

In Jerusalem, at the tenth bi-annual conference of Kolech, the Religious Women’s Forum, Dr. Ronit Irshai stood up and looked around the full conference room.

“Where is everyone?” she said. Irshai is a scholar of gender studies and Jewish law at Bar-Ilan University, a leading feminist and author of ground-breaking work on fertility and Jewish law.

“If our movement has moral right on its side, where are all the other religious Jews?” She asked. “It is too easy to say that the patriarchy is digging in, defending itself. We need to look for other answers. How can we make an opening for conversation with others including those in the rabbinic establishment? Perhaps we seem to others as if we are asking for everything, as if there are no boundaries to what we want addressed, from agunot to LGBT, there is nothing that can be left as it was.”

In fact, the Israeli religious women’s movement has always cast a wide net in its demands and in its mission. Yesterday’s Kolech conference clarified just how much Israeli religious feminism differs from American and how much the scene here has fostered an indigenous movement with its own challenges and opportunities. Kolech was founded in 1998, in the wake of the establishment of JOFA, the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance. While American Orthodox feminism is currently consumed by the pushback from the rabbinic establishment against female clergy, its Israeli partners are wondering about other issues.

With the responsibilities of a sovereign state never far from mind, some religious feminists think the time has come to move beyond women’s issues, to consider any and all issues of social justice.

“What concerns any Israeli, any part of the collective of Israel, should concern us,” claimed Malka Puterkovsky, an expert in Jewish law and a renowned educator of decades. “We should be a force to reckon with in the fight against prostitution, sexual harassment and abuse, but also for the disabled in Israel, for all matters of social justice.” A woman in the crowd echoes this sentiment, “We should be on the front pages of the news in all these cases.”

For many of the women in the Kolech audience, the big issue seemed to be inclusion: How to reach women in the Ethiopian community, the Mizrahi community, and Haredi community — those who live outside the educated Modern Orthodox Ashkenazi world so often described as ‘elite’. Kolech, though, keeps reaching out and the conference included panels on non-traditional families and single mothers, too.

Rabbi Ethan Tucker, founder of Mechon Hadar in New York and a presenter at the conference, offered a radical idea that crossed the cultural boundaries of the American-Israeli divide: For decades, he said, religious women have been categorizing their participation in increased ritual and learning as “permission,” as “allowance.” What if we turned the tables, said Tucker, and conceived women’s participation as a question not of permission, but of obligation; of religious stringency (humra) not allowance (kula)? Rhetoric can often be nothing but spin, but in this case, the rhetoric is much more than that. What’s at stake in this rhetorical shift is the idea that with the other half of the Jewish people obligated in the performance of mitzvoth and the learning of Torah, God’s name is doubly sanctified, the Torah is doubly glorified.

Tucker is American but his message –- in Hebrew — was one that characterizes Israeli religious feminism whose discourse is rarely one of rights and claims. Over and over, what one hears in Israeli religious feminism is God’s name: This is a revolution in sanctification of the divine name, of glorifying Torah, of perfecting the created world, its proponents say. There is no language here of democracy, of equal rights. The theological and devotional language reflects a deep immersion in the culture of Torah study — the comprehensive world of religious practice and belief, to which there is no “outside” — that distinguishes the Israeli cultural world from its American counterpart.

In a panel on women as halachic authorities and rabbis (a panel so full that men and women were lining the aisles and sitting in the floor), I was struck by the way that Israeli women seeking ordination are not impractical, but instead, unworldly in their considerations. It is not clear what the professional opportunities are, it is not clear what scope of institutional support they will find, it is not clear what they will disqualify themselves for, but these questions seem to matter to them much less than to their American counterparts. The path is defined by other terms and the future at stake is no less than the religious culture of the nation their daughters and sons will inherit.

The Rabbanit Devora Evron and Rabbanit Rachel Keren, both mothers, grandmothers and educators of decades, spoke of years studying for the exams of the Chief Rabbinate. (There is currently a petition in preparation before the Supreme Court asking for permission for women to take such exams.)

While the State does not recognize them as rabbis, Keren, who has been studying halachic texts since she was a child at her grandfather’s knee, described this as merely a “political” obstacle that would, in time, be overcome.

Evron described coming upon a call for applications for a rabbi in an Orthodox Israeli community; she fit every single criterion listed. So she applied. “When the rejection letter came,” said Evron simply, “it was a letter of real substance, of regret, respect, and attention. It was the kind of letter that said, yes, you answer all our desires, but between us, we cannot be the first.”

Evron seems to be living in the space between what we know can’t happen, but just might sometime soon. There is no shortage of heartbreak, in the current limitations, but these women are involved in active teaching lives and the next generation is very much on their minds.

The fight for synagogue participation, for Talmud education for girls, the issues that defined my generation, aren’t over in many places.

But the progress over the years – and the new questions — are unmistakable.

Ilana Blumberg is Director of the Shaindy Rudoff Graduate Program in Creative Writing at Bar Ilan University and the author of the prizewinning memoir, Houses of Study: a Jewish Woman among Books.