Meet Moses Elisaf, The First Jewish Mayor In Greece, The Cradle Of Democracy

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The municipal elections of a small city may seem like an unlikely way to make history after 2,300 years of history, but that’s what happened in June when the Greek city of Ioannina elected a Jew as mayor — the first ever in Greece, despite widespread anti-Semitism.

The mayor-elect of Ioannina, from a region subject to the Ottoman Empire until 1913, is named Moses Elisaf. He’s 65 years old and a Romaniote Jew, descendant of the oldest Jewish diaspora in Europe, founded by Jews receptive to Greek culture who built their earliest known synagogue in the 2nd century B.C.

Despite the community’s long history, and in Elisaf, the political victory of a native son, the question of how long Ioannina will be home to Jews is ever-present.

“We have to work to keep the traditions, the monuments. I have a lot of obligations now to honor the citizens of my city, and also as a Jewish leader,” said Elisaf, adding, “I’m not sure that this community can stand for a long time.”

Ioannina is a bustling university town on a mountain lake; its landlocked charm is one of the best-kept secrets in Greece, which famous more for its telegenic Aegean islands. The acropolis rises from Byzantine castle walls near the square where the Nazis deported the Jewish population on March 25, 1944. The mayor’s office would not recognize these facts until 2006, when research made headlines.

Indeed, a vote for Elisaf was not a statement in favor of multiculturalism. He is a doctor and a professor of medicine; independent financially and politically. People voted for him to stand against corruption, and even then, his victory was a narrow one — by 200 out of 40,000 votes cast. Elisaf is married and has no children.

“The people know who they voted for. I was elected despite the growing anti-Semitism all over the country. It is well known that Greece is a country with a great rate of anti-Semitism, but it is verbal. It’s not violent,” said Elisaf, relieved not to have heard slurs directly during his campaign.

Elisaf, who served on city council twice in 2006 and 2014, is outspokenly Jewish. He does not separate his Greek and Jewish identities, nor does he see a conflict in remaining president of the Jewish community, a position he has held for nearly 20 years.

A week after the election, Elisaf sat confidently in his community’s Old Synagogue, which was saved during World War II by an Ioannina mayor who convinced the Nazis it was a library. Sunlight stretched over the empty wooden benches in the oldest and largest synagogue in the Balkans, full only once a year now for Yom Kippur. A Romaniote cantor named Haim Ischakis flies in from Athens, proud of his Ioannina roots.

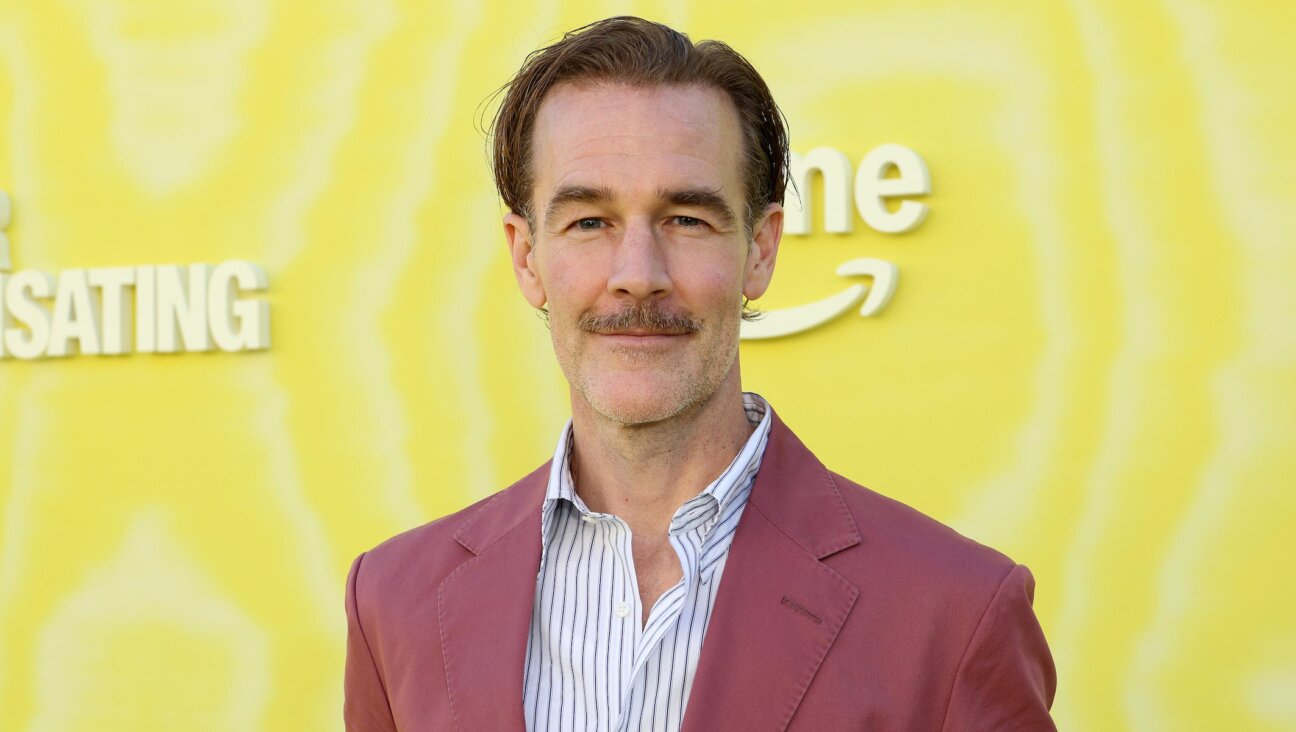

In a first for Greek democracy, the small town of Ioannina has elected a Jewish mayor; he also leads the Jewish community, and oversees the care of this synagogue. Image by Matt Hanson

A series of marble plaques around the ark and bima remember 1,832 Holocaust victims, their names engraved in the stone. There’s a good chance the interior is going to be turned into an exhibition space. The remains of the city’s second synagogue, ruined during WWII, are on display thanks to communal efforts curated by Greek-Jewish museologist Esther Solomon.

Despite the decline in synagogue attendance in Ioannina, Greece is center stage for a little-known Jewish story, that of the Romaniote: they speak Greek, and descend from a group indigenous to Hellenic lands prior to Christianity. “Romaniote” is a scholarly term that connotes their influence by late Roman culture.

Relatively speaking, then, Ioannina is a young Greek-Jewish community, though legends say Jews were lured to its mountains since the high priest of Judea met Alexander the Great, whose mother was from Epirus. The earliest written evidence of Jewish presence in Ioannina dates to 1319 in the Byzantine era. The oldest tomb is from 1427. While the cemetery is badly overgrown, the Sisterhood of Ioannina in New York is funding cleanups. There’s a vibrant Romaniote community in the New York City area.

Ioannina was the heart of the Greek Enlightenment, and preserved Romaniote cultural identity into modernity, specially through the poetry of Joseph Eliyia and the scholarship of Rae Dalven. Elisaf will be in office during the Greek bicentennial in 2021.

“We’re in a good place now in Ioannina. We are not losing that Jewish community so fast,” said Marcia Haddad Ikonompoulos, who first visited Ioannina in 1973, and currently directs Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue Museum in Manhattan, the base of Jewish-led Greek-American support since the community incorporated itself as a legal body with the Supreme Court in 1914.

“My regular trips have let them [in Ioannina] know, we’re not going away. The eyes of the world are on them now,” said Ikonomopoulos, who plans to go to Ioannina three times this year, encouraging the Jewish community’s diaspora. Thousands proudly identify as Ioannina Romaniotes in America and Israel.

Yet the shadow of Jew hatred hangs over even the optimistic Elisaf. In the 2000s, members of the Golden Dawn desecrated his mother’s grave when they repeatedly vandalized the Jewish cemetery in Ioannina.

Local reporter Alekos Raptis, who won a state award for his reportage on the 1944 deportations, investigated the vandals, landing Golden Dawn in court. Christos Pappas, the party’s second-in-command, languishes under house arrest in Ioannina.

In 2009, the people of Ioannina formed a human chain around the cemetery in solidarity. After the municipality installed motion-sensor lights and cameras that year, vandalism stopped. Anti-Semitic vandalism outside the Old Synagogue persists.

While nearby Larissa closed its Jewish school last year for its community of 300, Ioannina’s few young Jews are choosing outmigration and intermarriage. The cemetery and Old Synagogue are in the hands of the Byzantine archaeological authority for posterity.

“Our idea, with Moses, is just to be able to leave something, not to erase the past, and try to persuade Ioannina to keep it,” said John Kalef-Ezra, a professor of medical physics and a colleague of Elisaf at the University of Ioannina, together with three other Jewish community members, an impressive ratio of local Jews among the professional elite. “In Greece, only two [Jewish] communities can survive: Athens and Thessaloniki.”

Matt A. Hanson is a journalist based in Istanbul, originally from Massachusetts. He is of Romaniote heritage himself; his grandfather’s parents immigrated to New York from Ioannina.