Nazi collaborator monuments in Kosovo

Xhaver Deva, who helped create the SS Skanderbeg, has two streets named after him in Mitrovica and Pristina

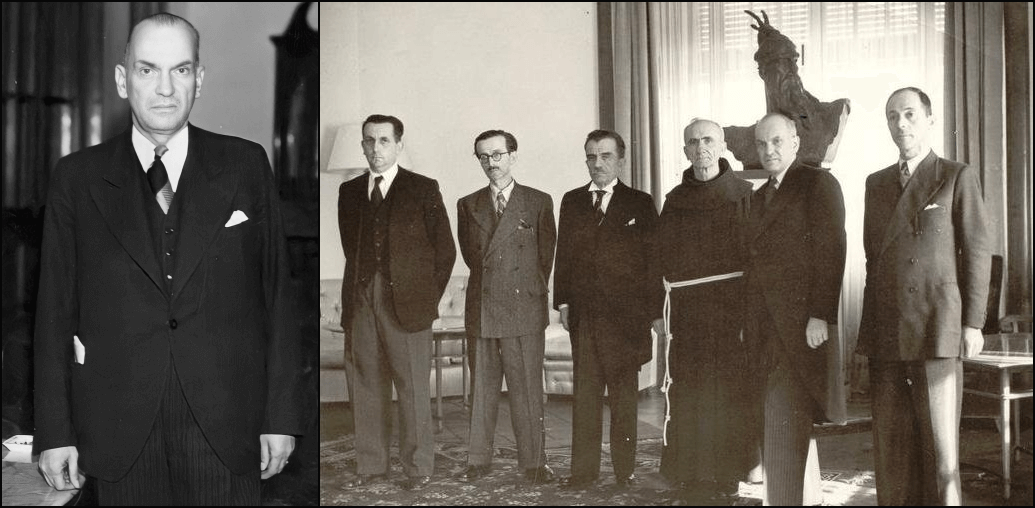

Left: Rexhep Mitrovica (General Directorate of Archives via Wikimedia Commons). Right: the Albanian Regency Council, with Mehdi Frashëri third from left, Anton Harapi fourth from left and Rexhep Mitrovica fifth from left, 1943 (Wikimedia Commons). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Mitrovica and Pristina — Both cities have streets honoring Xhaver Deva (1904–1978). Deva, a Kosovo Albanian, was a leading figure in the political and paramilitary movement Balli Kombëtar, which collaborated with the Nazis and envisioned a Greater Albania based on the notion of “Albania for Albanians.”

In 1943, Deva became minister of interior in Albania’s newly-formed Nazi collaborationist government; in February 1944, forces under his command massacred 86 people suspected of being fascist resistance members in Tirana. Deva also recruited for the 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS “Skanderbeg” (1st Albanian), an Albanian Muslim formation in the Waffen-SS, the military arm of the Nazi Party. Shortly after SS Skanderbeg’s formation, its members rounded up and deported at least 281 Kosovo Jews — some researchers cite higher numbers — many of whom were subsequently murdered in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. After the war, Deva fled to the U.S. where he, like many ex-Nazi collaborators, enjoyed a productive relationship with the CIA.

A complicating factor in Deva’s legacy stems from the fact that the collaborationist government he was part of controlled not only Kosovo — a region north of Albania proper which was annexed to Albania in 1941 — but also Albania proper. The fate of Jews in Albania proper is markedly different from that of Jews in Kosovo.

Albania has an incredible history of saving Jews during the Holocaust: it is the only European nation to emerge from WWII with more Jews than it had in the beginning. Scholars suggest various reasons such as besa, the Albanian honor code which demands protection of guests and strangers seeking asylum, and the Third Reich’s relatively loose control over the countryside.

According to at least one Jewish survivor, Deva himself resisted handing over lists of Jews in Albania proper when pressured to do so by the Nazis. Unfortunately, due to the relative lack of research on the Holocaust in Albania, the extent to which the country’s collaborationist government aided versus resisted the Nazis is difficult to determine.

What is known is that Deva and other members of the Albanian puppet state were responsible for the creation of SS Skanderbeg, which sent Kosovo Jews to their deaths. Their government also resisted, to some degree, Third Reich demands to assist with the identification and roundup of Jews in Albania proper.

Deva surfaced in the news in February 2022, when it was discovered that the European Union and the United Nations Development Center were funding the renovation of his house in Mitrovica. After pressure from the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the German ambassador to Kosovo, the EU and the UN dropped their support of the restoration.

However, Deva’s house, which dates back to the 1930s, is not a monument to Deva in and of itself. It’s an existing historical structure and, as former Kosovo politician and journalist Veton Surroi noted on Twitter, “a building cannot inherit the sins of its builders.”

The restoration project would only become problematic if the house were to be transformed into a museum that whitewashed Deva’s legacy. If that happens, Deva’s house would qualify for inclusion in this project. As of April 2022, only Deva’s streets in Mitrovica and Pristina count as honors to a Nazi collaborator.

See the North Macedonia section for two statues of Balli Kombëtar leaders. Pictured above right is a SS Skanderbeg recruitment station in Prizren, 1944. Pictured below is a German military officer with Chetnik leader Kosta Pećanac and Deva in Podujevo in 1941.

***

Pristina and two other locales — Kosovo’s capital, Pristina, has several streets honoring members of Albania’s Nazi puppet government. These include streets named for prime minister Rexhep Mitrovica (1888–1967), above left, who also has a street in Mitrovica; minister of education Rexhep Krasniqi (1906–1999); and Anton Harapi (1888–1946), the Franciscan friar who was on the High Regency Council (Harapi has a second street in Peja). Mehdi Frashëri (1872–1963), another High Regency Council member, has a street in Mitrovica.

Above right, a meeting of the Albanian Regency Council, 1943, with Mehdi Frashëri third from left, Anton Harapi fourth from left and Rexhep Mitrovica fifth from left.

Gjurakoc and two other locales — Three sites in Kosovo honor Mid’hat Frashëri (1880–1949), a key figure in Albanian nationalism who became president of the Balli Kombëtar movement. Under Frashëri, Balli Kombëtar collaborated with Nazi Germany, including militarily. After the war, Frashëri established a working relationship with the CIA (see the New York Times reporting). In addition to his school (with a bust, above right), he has streets in Mitrovica and Pristina. See the Albania section for more streets to Frashëri as well as other Albanian Nazi collaborators.

Pristina (entry added June 2025) – A street honoring Aćif Hadžiahmetović, also known as Aćif Bljuta and by the honorific Aćif-efendija (1887–1945). The mayor of Novi Pazar in what was then Yugoslavia, Hadžiahmetović eagerly supported the Nazi invasion of his city, throwing a festive banquet for the Germans.

During his mayorship, his forces slaughtered Serbs and deported all the city’s Jews to be liquidated at the Staro Sajmište concentration camp. Hadžiahmetović received the Iron Cross (Third Reich military honor) for his services to Germany.

Above right, Jews being registered for forced labor shortly after the German invasion of Yugoslavia, 1941. See the Serbia section for more Hadžiahmetović honors and information on scandals surrounding the campaign to rehabilitate him.