Bernie Sanders took pride in being a Jewish presidential candidate, a former aide says

In a memoir, Ari Rabin-Havt writes about Sanders’ reluctance to discuss his Judaism in public

Senator Bernie Sanders speaks during an Amazon Labor Union (ALU) rally in the Staten Island borough of New York on April 24, 2022. Photo by Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg via Getty Images

On the campaign trail, Bernie Sanders didn’t relish talking about his Jewishness. But one of his closest aides is more than willing to go there in a new book about the senator and former presidential candidate — who is flirting with a third run for the White House in 2024.

Sanders came closer than anyone to becoming the first Jewish president in U.S. history after decisive wins in early primary states in 2020, before Joe Biden mounted a surprise comeback in the South Carolina primary.

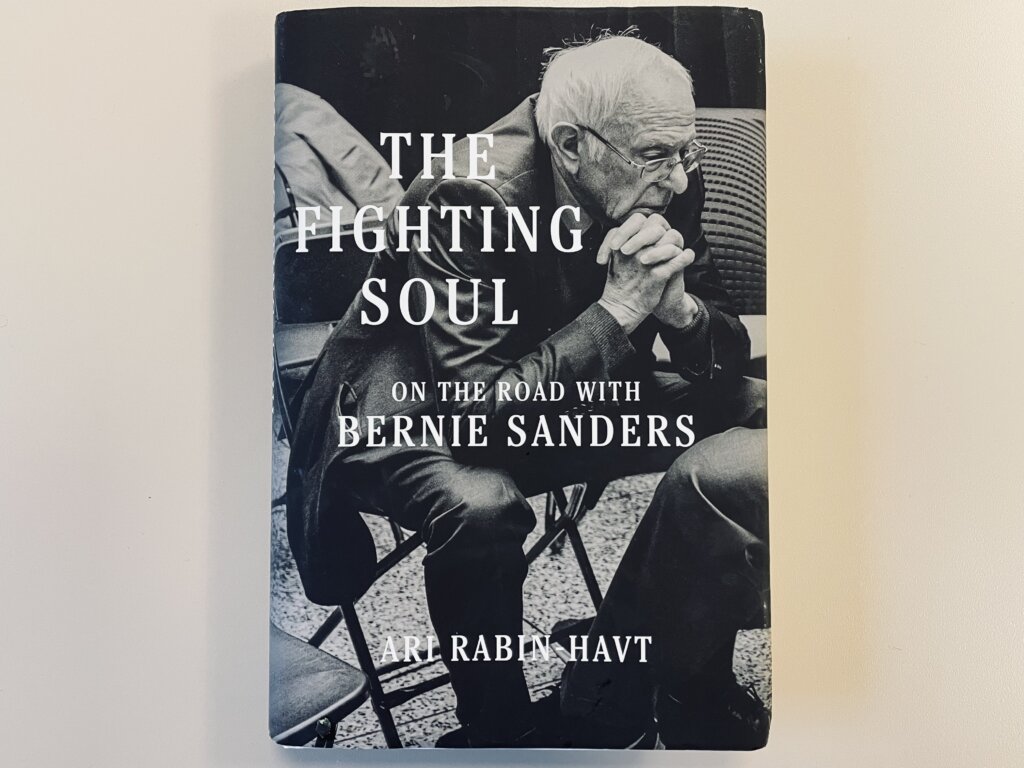

“My parents would tell me I was crazy if I told them I would become a senator, much less could become president of the United States,” Ari Rabin-Havt, who served as deputy campaign manager in 2020, recalls Sanders telling him on several occasions in the book, published last month and titled The Fighting Soul: On the Road with Bernie Sanders. The book is filled with behind-the-scenes anecdotes, many of them revealing how Sanders sees himself within the Jewish world.

Rabin-Havt, who is also Jewish, was in a position to know. He became one of Sanders’ most trusted aides since he started working for him in the Senate as a senior advisor in 2017 and stood by his side during the 2020 primaries.

The author said he wrote the book to “explain who Bernie Sanders — an elderly Jewish socialist from Vermont who managed to capture the imagination of the young people of America and transform our country — really is.”

And part of who Sanders is, Rabin-Havt said in an interview, is a man very conscious of being the first Jewish candidate in serious contention for the presidency. It “was a personal point of pride for him,” the author said, even though Sanders doesn’t like to talk about it, preferring to focus on his views on policy.

Antisemitism on the campaign trail

Sanders, who ran for president in 2016, decided two years later to make a second bid for the presidency, in the living room of Rabin-Havt’s Washington apartment, the author writes. During that campaign, he continues, the candidate was chagrined by several antisemitic attacks against him.

Sanders objected to a Politico article about his wealth that featured a graphic picturing him next to a tree made of money in the front yard of his home, and a CNN chyron comparing him to the coronavirus on the morning of the South Carolina primary. Earlier in the campaign, a supporter of Donald Trump held up a swastika behind Sanders during a campaign rally in Arizona.

Though Sanders spoke somewhat more publicly about his Judaism in his 2020 run, as compared to his 2016 bid, he still did not want to make an issue when people tried to use his Jewishness against him, Rabin-Havt wrote. Sanders “is not religious, and he never wanted to point out these affronts in public for fear that he would be seen as using his Judaism only when convenient.”

In April 2019, Sanders forbade his campaign staff from publicizing a visit he paid to the site of the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, where 11 people were killed in a terror attack in 2018 because he didn’t want the visit to be seen as a “publicity grab.”

But though not observant, Sanders still strongly identifies as a Jew, according Rabin-Havt. On the way to the temple to meet Rabbi Jeffrey Meyers, the author writes that he told Sanders that the rabbi might want to say a mourner’s kaddish at the site and asked whether he knew the traditional Jewish prayer in honor of the deceased. “Ari, Yitggadal veyitkadash shmay rabba,” Sanders said in an “annoyed tone,” reciting the first line of the prayer.

“I am Jewish,” he told his aide.

Bernie vs. AIPAC and other pro-Israel groups

During both of his presidential campaigns, Sanders drew the ire of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee for declining to attend their annual policy conference in Washington, D.C.

Rabin-Havt details a 2018 incident in which Sanders became agitated by the suggestion that his staff would consult with the largest pro-Israel lobby in the U.S. on a strategic move that would advance key legislation important to him.

Sanders was at the time attempting to pass a bipartisan resolution aimed at ending U.S. support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen by strengthening Congress’ foreign policy powers. Republicans had introduced an amendment to the resolution that would assure it would do nothing to disrupt military operations and cooperation with Israel. The idea was to put the Democrats, who wanted to pass the bill quickly, without amendments, in the awkward position of having to vote against cooperation with Israel to keep the bill streamlined.

Ahead of the debate on the Senate floor, Rabin-Havt was in the Senate cloakroom with a team of advisors suggesting a move that might ease passage of the bill when another Democratic staffer asked if he had consulted with AIPAC on the idea. “No one on my staff will get permission from AIPAC for anything,” Sanders interjected. Rabin-Havt writes that “the irony, of the most prominent Jewish lawmaker in the United States angrily objecting to his team consulting with the country’s leading Israel lobby, was not lost on anyone, except perhaps Bernie.”

The amendment passed unanimously in the Senate, and the resolution by a 56-41 vote, but former President Donald Trump vetoed it. What it reveals about Sanders, Rabin-Havt writes, is his strong belief that no outside group should influence his vote.

If Sanders had won the Democratic nomination and been elected president, there would have been a shift in U.S. policy towards Israel, in line with J Street, the liberal pro-peace group, Rabin-Havt said.

The author also describes “deeply distressing” ads funded by the Democratic Majority for Israel in the 2020 campaign that questioned Sanders ability to beat Trump in the general election. He criticizes DMFI for objecting to Sanders’ position on Israel but not mentioning that in any of the TV commercials, calling it “somewhat dishonest.”

And he writes about a contentious meeting with DMFI’s chief executive Mark Mellman, at campaign headquarters, in which Mellman said that Sanders public remarks about his father coming from Poland — and downplaying his Jewishness — “was a mockery of his heritage and evidence to some that Bernie was a self-hating Jew.” Rabin-Havt also wrote that Mellman wrote letters asking the campaign to distance itself from Muslim surrogates.

Mellman in an interview said Rabin-Havt’s account of the meeting is “fictionalized.” Only towards the end of the meeting with Sanders’ advisors, he said, did he suggest that some Jews were distressed that the candidate described himself as the son of Polish immigrants when most Jews at the time didn’t consider themselves Poles and that he never used the word ‘self-hating Jew.’

Mellman said he did question Sanders’ judgment related to two prominent campaign surrogates — Amer Zahr, a Palestinian-American comedian; and Linda Sarsour, a Palestinian-American activist — because of their public records of making antisemitic statements.

Why Sanders never got to the Promised Land

Rabin-Havt recalls a meeting between Sanders with former President Barack Obama before he launched his second bid for the presidency.

“Bernie, you are an Old Testament prophet — a moral voice for our party giving us guidance,” he recalls Obama as saying. “Here is the thing, though. Prophets don’t get to be king. Kings have to make choices prophets don’t.”

Obama advised Sanders to soften his approach to broaden his appeal within the party, but that wasn’t a tack Sanders could take, Rabin-Havt writes, because “he wouldn’t be Bernie” if he did.

“Bernie Sanders will never see the promised land himself, but he has still managed to move this country in a more progressive direction than any other person who failed to win the White House,” he writes

NBC has reported that in recent weeks, Sanders has consulted with his close aides about a possible run for president in 2024 if Biden doesn’t run for re-election. And former campaign manager Faiz Shakir wrote in a private memo that Sanders hasn’t ruled out a run.

Rabin-Havt said that when he finished writing the book he predicted that 2020 was the last presidential campaign for the 80-year-old senator. “But Bernie Sanders is somebody who has an unstoppable amount of energy that is almost inhuman,” he said. “So if he says it’s something he can do, he can do it.”

But Rabin-Havt, 43, said he lacks that energy and wouldn’t join another grueling campaign.